When we had our first project meeting with our mentors, we were both excited and concerned about the material we would explore over the summer. Given our social identities and background in humanities, we had to contend with the distorting tendencies of western academia towards the Middle East, a phenomenon we had encountered in past academic experiences. Already primed to notice distortions in our anti-Orientalist and postcolonial studies, we now were tasked to apply alternative methodologies. While intimidating as undergraduate students, we were immediately comforted by our shared sensibilities upon that first meeting. Out came a productive, respectful, and unifying dialogue between us students and our mentors.

We were led by a determination to authentically interact with each other and the material; so we chose to meet in-person consistently. Because of this, our dialogues were a key component of the project. We began by reading articles, poems, and books about Iraqi politics, learning about authoritarianism, occupation, and sectarian division, among other topics. We met weekly over iced drinks to discuss our reflections, independent research, and what it would mean with regard to selecting the Artist’s Statements of the Shadow and Light Project.

We decided upon the criteria for these statements: awareness of positionality, publishing legacy of the academic, variety of academic disciplines represented, and a heartfelt message. From the sixty statements, we selected twenty-five (five to spare). Evyn, one of our mentors, requested these twenty-five from the founder, Mr. Beausoleil, and they shipped to us the following week.

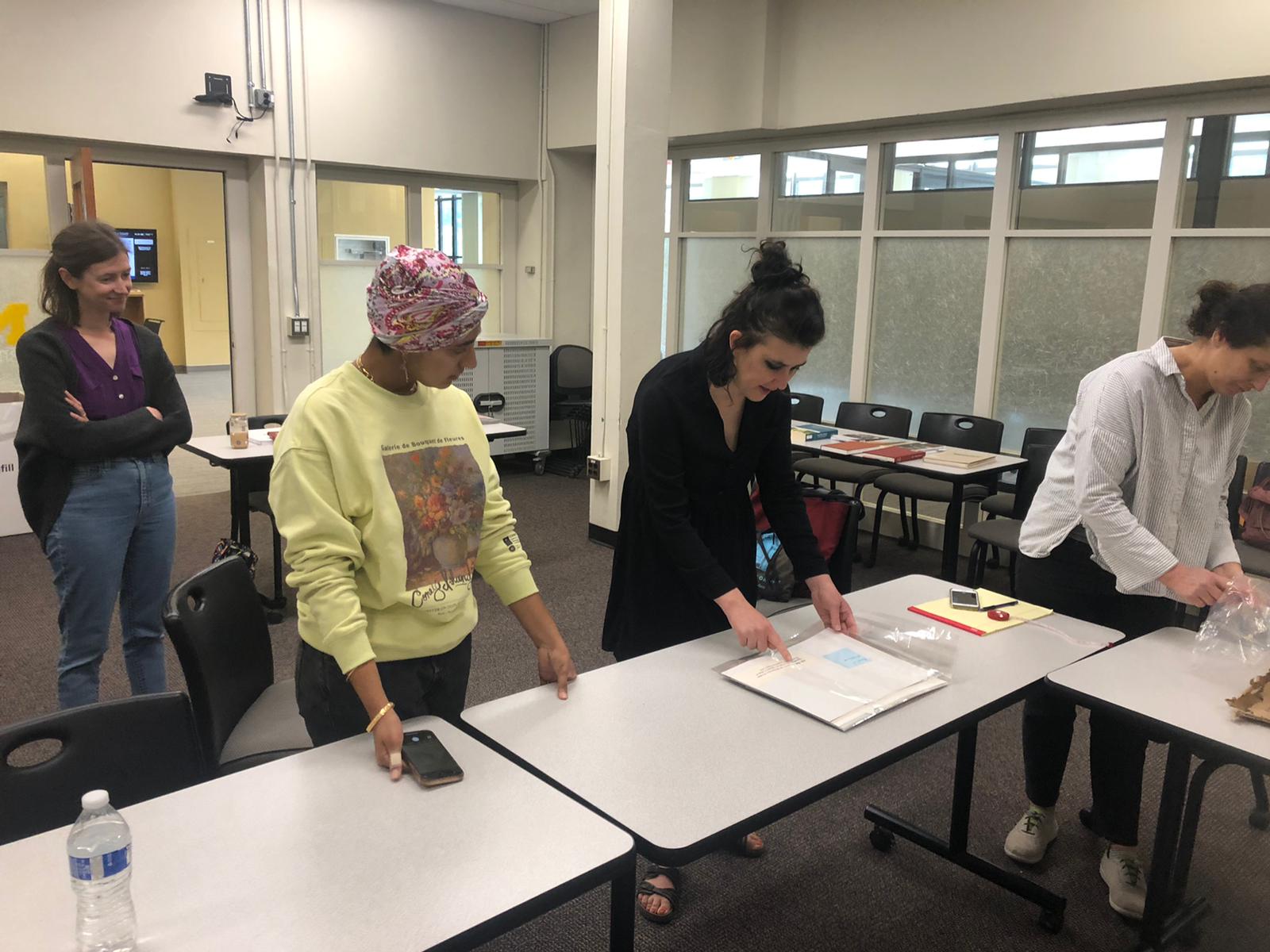

Here we are getting ready to look at the photographs.

A new criteria critically emerged: visual interest. It certainly was a learning moment for us – the integration of the visual exhibit we had been assigned and the argumentative essay we had been mentally compiling. Five more statements were excluded on the basis of substandard composition, which we had anticipated since the statements were commissioned from everyday people. We appreciated their work, and slipped them back into their packing envelope.

At this point in early June, our contributions to the physical exhibit were complete. For the next seven weeks, our focus turned to the online exhibit. Although we had casually brainstormed before this point, the new Omeka training had grounded us to the possibilities and expectations of the format. Thus, we started from scratch on our thesis, but that, too, was more complicated than expected.

The alternative methodologies we had tested while selecting the statements now had to apply in a much more generative way - writing. Did we want to recreate the same exhibit in a new platform? Or were we wishfully peering around the corners of Shadow & Light’s boundaries and into the implications of political violence and art? Definitely the latter.

Encouraged by our mentors, we invited Mr. Beausoleil to a zoom conference and relayed our questions to him - what was the scope of this project? Who was the audience? What exactly was this experimental exhibit in grief and solidarity with political victims?

These big questions were entertained, but as expected, couldn’t be answered concretely. Instead, he gave us something more valuable: permission to expand based on our values. It was this permission that propelled us forward into our many theses.

For two weeks, we chatted excitedly over sequels upon sequels of Google Docs. We made bullet lists, outlines, and then all shapes and lengths of theses. It was a struggle to settle upon our subject: was it the humanities in wartime? Institutions under occupation? Was it the students whose education was cut short and distorted? Or the rise in sectarian values?

We drafted a thesis that attempted to combine all of these subjects and presented it to our mentors in the Hatcher Library. They listened attentively and then gave transformative feedback: we can focus on the objects and shape the narrative around them, or choose the objects according to an intended narrative. The importance of the objects had escaped us entirely, but now, it gave us the clear path we needed. We left the library with our assigned objects (library books that the mentors had selected) and got to work.

Once we began to imagine the books we read and the photos we viewed as objects to comment on rather than information to cite in an essay, it was smooth sailing. Each of us went home and summarized our assigned readings, drafted an argument for how it could serve us, and earmarked interesting visuals. At the cafe, we’d explain our findings to one another. From there, we noticed patterns in our arguments and decided to group the objects into their respective topics.

- Iraq had a thriving public art scene in its early post-revolution years

- Art then suffered around political conflict, which led to the displacement of artists and a wave of striking political art for the international audience

- Following the American occupation, artists showed resilience in exile

- Commentary on Iraqi political art and struggle has been helpful and hurtful in the international market

Keeping in mind our exhibit writing and image description training, we began drafting according to the guide assigned to us: image description, context, and interpretation. For four weeks, we went back and forth with our image selections, finally grappling with the leading role the objects would play in the exhibit. When the images do the heavy lifting of an argument, it requires both an aesthetic and communicative criteria.

During this time, a new “member” entered our group by way of significant contribution: Serena’s father-in-law, who happened to be an art academic in Iraq during the time of our studies. Although he had been a helpful resource before, it wasn’t until we realized how integrated he truly was with our material that we decided to include him as a primary subject in our exhibit. He lent us his personal mementos as well as objects from the local Iraqi art community. It was his contributions that comprised our third section as well as the latter half of our fourth.

This final month was our most generative, and after submitting and revising our online exhibit draft for review, we have concluded this section. Now, we wait for the adjacent events that will be happening in the winter semester, and of course, the exhibition this fall. We are so grateful for the opportunity to guide the exhibit towards our neighboring communities and to envision history as belonging to living subjects.