The following post was authored by Leigh Gialanella, graduate of the UM School of Information and former student employee in the Library’s Digital Preservation Office. Leigh now works at the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History as a contract archivist, working with United States Geological Survey collections.

The term “born-digital” refers to documents, datasets, artwork, websites, and other materials that originate in digital formats. Born-digital materials can be found on computers, mobile devices, CD-ROMs, floppy disks, and other removable media.

Time and poor environmental conditions pose the most significant threats to born-digital materials. Most removable media have short shelf lives and can be expected to last anywhere between five and fifty years in perfect environmental conditions. The rate of external and internal deterioration increases substantially in media exposed to high temperatures, moisture, magnetic fields, dust, and other unfavorable conditions. To make matters worse, older removable media and file formats are increasingly becoming obsolete as modern technology evolves. The University of Michigan Library’s Digital Preservation Office aims to preserve born-digital materials on removable media before time, environmental conditions, and technological obsolescence render such action impossible.

Over the course of the last four years, the Digital Preservation Office has researched and developed a workflow for archiving and preserving born-digital materials. My responsibility this past summer was to follow this workflow and adapt it from words on a page into a production model centered on preserving born-digital content from the University of Michigan Library’s Robert Altman Digital Physical Media collection.

The Robert Altman Collection In 2008, the University of Michigan Library received a large collection of photographs, film scripts, correspondence, and other materials from the estate of the deceased Robert Altman, the critically-acclaimed film director, screenwriter, and producer. Among the items in this gigantic collection, measuring approximately 1000 square feet in total, are 632 pieces of removable media containing born-digital materials relevant to Altman’s work. The Robert Altman Archive Digital Physical Media Collection contains external hard drives, floppy disks of all sizes, CD-ROMs, DVDs, and a host of other drives and disks from the 1980s and 1990s.

Following the University of Michigan Library’s acquisition of the born-digital-heavy John Sayles collection later in 2013, the need for a pilot digital preservation project became increasingly clear. Altman seemed like the logical choice. Although the University of Michigan Library has plenty of removable media in its collections, the Robert Altman collection was the first of its kind to receive significant preservation attention on account of its expansiveness and renown.

From The Robert Altman Archive Digital Physical

Media Collection report by Jennifer Kremyar, pg. 7

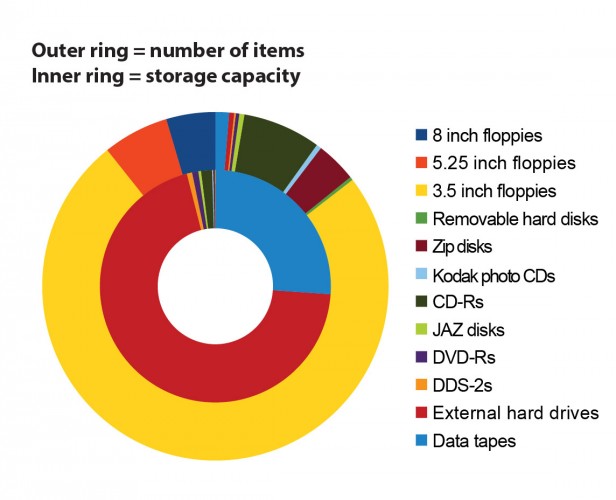

As illustrated in the above graphic, the three external hard drives in the Robert Altman Digital Physical Media Collection house the majority of born-digital materials in the collection. It was therefore imperative that their contents be ingested and preserved as quickly as possible. Following the ingest and subsequent preservation of the materials on the external hard drives, Library staff chose to prioritize Robert Altman’s collection of 473 three-and-a-half-inch floppy disks. Unlike the external hard drives, the floppy disks contain only a fraction of the collection’s born-digital content. Floppy disks are, however, extremely sensitive to environmental conditions and subject to rapid deterioration over time. To further complicate matters, even the most well-preserved floppy disks are becoming obsolete as new technology replaces them. It was also determined by comparing the labels on the media with the existing paper collection that materials saved on older media were generally printed and part of the paper collection, whereas files contained on 3.5 inch media existed only on that digital media. Because parts of Robert Altman’s digital physical media collection date back to the 1980s and 1990s, many of the floppies were already living on borrowed time. Prompt action was therefore needed to ensure that as many floppies as possible were ingested and preserved.

Prior to my joining the project, the Digital Preservation Office and its student workers had developed an ingest workflow and pioneered it on the three hard drives in the Robert Altman collection. My role in the project was to begin ingesting the three-and-a-half-inch floppy disks.

Workflow The University of Michigan Library’s digital preservation efforts center on the creation of disk images: bit-by-bit copies of the contents of a storage device. The disk images we create are known as “forensic images”, since they capture existing files and file structures as well as deleted files and unallocated disk space.

In simplest terms, the Digital Preservation Office’s ingest workflow involves imaging removable media, creating metadata, running a series of tests and reports on the resulting disk images, and packaging the disk images, reports, and metadata together for transfer into library storage. Once in storage, the disk images and their associated materials are backed up and secured for the foreseeable future. Years down the line, staff at the University of Michigan will be able to locate the disk images alongside the supplementary materials needed to interpret them.

The Digital Preservation Office’s ingest workflow is comprised of the following steps:

- Barcode the floppy disk.

- Photograph the floppy disk. It is useful to have a photograph in case something happens to the original disk. Most floppy disks ‘wear’ their contextual information on their exterior labels, making photographs that much more important.

- Create a disk image of the floppy disk. Input metadata into an associated .info file.

- Run a virus scan on the disk image. If a virus is found, the disk must be quarantined.

- Mount the disk image to see if its contents are accessible.

- Run reports on the disk image to locate sensitive information, such as social security numbers, email addresses, and phone numbers. We do not want future users of the collection to come across this information while browsing content.

- Create more metadata on the imaging process. Package disk image, metadata, photographs, and reports together using archival software called Bagger.

- Transfer the resulting ‘bag’ to preservation storage.

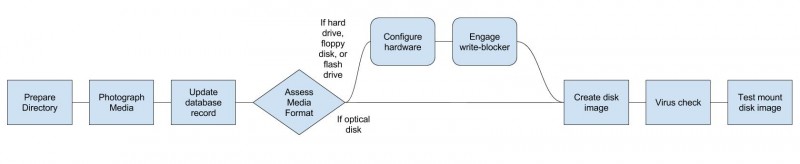

High level imaging flowchart by Noa Kasman

High level imaging flowchart by Noa Kasman

With the exception of barcoding and photographing the floppy disks, our workflow is conducted on a Linux machine running BitCurator, a suite of digital preservation programs and tools. Relevant programs used in the workflow include Guymager (disk imaging), ClamTk (virus scanning), BitCurator Reporting Tool (reporting), and Bagger (packaging for storage).

At multiple points during our workflow, we ran checksums on our disk images and bags to ensure that the original files did not change during format conversions and transfers to storage. As part of the imaging process, we transcribed the labels on the floppy disks and recorded associate drive names. Later on, while creating metadata in Bagger, we noted what stages of the workflow had been completed and to what degree of success they had been carried out. Future custodians of this collection will need to know what procedures the floppy disks and disk images have undergone.

Part 2 of this post will address our experiences using the above workflow on the Altman collection.