In April 2023, the U-M Library opened a newly renovated floor, the Clark Commons, on the 3rd floor of the Shapiro Library. Through this renovation, made possible by generous funding from Stephen S. Clark, the library aimed to create a cohesive experience organized by zones of activity meant to guide faculty, students, and staff to a variety of resources, services and expertise. In particular, the floor is made up of 8 distinct study atmospheres, each with different seating options and partitioned off from each other in intentionally designed ways. There are zones with booth seating, team spaces, more lounge-like seating, a silent reading room as well as areas with more natural lighting.

As soon as the floor opened (literally minutes after the floor was accessible to users) students flocked to the space. Its popularity was apparent to anyone walking by. At the same time, certain areas of the floor consistently had more open spaces than others while some spaces were full no matter the time of day. Trends like this can be harder to see and require systematic data collection and analysis to understand if the user behavior you may see one day is actually a sign of an overall use trend or just a one-off.

Assessment and UX Research Post-Renovation

During the first year the Clark Commons was open (April 2023-May 2024), I and a team of students collected a number of data points to assess whether the design goals for the public spaces on the floor were being met, and to try to capture usage trends. This was a big undertaking and took months to plan, collect the data, analyze the data, and finally report out on the results. Throughout this initiative, I used a combination of qualitative and quantitative methods to capture both attitudinal and behavioral data. I drew on my background as a UX researcher to mix more qualitative user experience methods with more traditional assessment methods like surveys.

In this blogpost, I describe two of the behavioral data collection methods used since they are somewhat more unique and were included to supplement data captured through surveys and interviews.

The Challenges of Capturing User Behavior

Behavioral data is data that reflects what people do as opposed to what people say they do or what people think they would do (both of which are attitudinal data and are generally less reliable than behavioral data). Having an accurate picture of the way users interact with a product or space helps show the strengths and weaknesses of that product. Since UX research and assessment are generally both focused on improving product experience, taking the time to capture behavioral data is highly useful even though collecting attitudinal data is a lot easier. The reason it is difficult to collect accurate behavioral data is because real-world usage would ideally be captured without any bias introduced from a researcher. Methods like usability testing try to approach real-world usage, but in actuality, they represent simulations where a researcher is directing product use, as opposed to observing real-world usage.

For space, theoretically, you could film a space like the Clark Commons and then analyze the results, seeing what furniture is used, what kind of actions people take, what traffic patterns exist, the noise level on the floor, etc. But in practice, you would be compelled to consider the cost of invading users’ privacy without their consent. Considering library professional standards on privacy, there is not a strong argument for capturing behavioral data in this way just for the benefit of an improved study space.

There are less invasive ways of collecting behavioral data. For interface design, anonymous log data of user sessions can show users interacting with a site and for space you can do things like map the walking paths users take within a space. But, even with these less invasive observation methods, you still aren’t able to know why users make certain decisions. You could assume what was going on based on past patterns, but you wouldn’t truly know.

Considering these challenges related to behavioral data collection, to try to capture our best possible understanding of Clark Commons use, we employed two more “behavioral-like” research methods and then later combined them with attitudinal data.

Seat Sweeps

The first method we used is commonly known as a “seat sweep.” This is an observation where a researcher walks through a space capturing a snapshot in time of what they see with the goal of better understanding traffic patterns, occupancy, peak capacity, furniture use, technology use, etc. For the Clark Commons, seat sweeps were conducted during Winter and Spring term over the course of 3 different weeks. During each week, 3 counts were conducted each day: morning (8am), afternoon (2pm) and evening (8pm). The dates of these count weeks were:

- 4/1/24 - 4/7/24 (a more “average” traffic week)

- 4/15/24 - 4/21/24 (a “peak” traffic week leading up to winter exams)

- 5/28/24 - 6/3/24 (a “low” traffic week during spring term)

Counts were conducted by hand to allow for more detailed, varied data collection. Seat counters were a team of trained, paid student employees who were identifiable with library lanyards and t-shirts. This was an intentional choice made to mitigate the perception from space users that they were being surveilled. All data was collected anonymously in the form of a checkmark noting each location where a person was sitting.

Side-by-side photos show observation count sheets from the same day. The count sheet on the left is a seat sweep conducted in the morning while the count sheet on the right was conducted during the evening. The evening count shows many more check marks as well as higher noise levels.

This method showed us trends of use but didn’t tell us anything about who was coming to the floor, why, how often, and what they experienced when there. To get closer to learning some of this information, I conducted a photo diary study.

Photo Diary Snapshots

A photo diary study is a user experience research method used as a way to get closer to observing use of a product, service or space. While this method still relies on self-reported data, that data is meant to be collected during use, raising the likelihood that you are capturing more accurate user behavior than a survey might. The intent of our study was to capture richer, qualitative data, through pictures taken by the participants, allowing us to see the experience of studying through their eyes. In addition, photo diaries coupled pictures of the study experience with information about the choices that led the person to study in the location shown. In this way, we added stories and visuals to the more quantitative seat sweep observations.

The questions asked in this study loosely followed the structure recommended by Nielsen and Norman for diary studies including questions meant to capture motivations, emotional state, and generally how people interact with the floor. Often, photo diaries are used to capture habits and behavior changes over time. While this would have been interesting to know, time limited me from capturing change in use over time. Instead, this was a short-term study where participants were asked to study on the floor 3 times between 4/10/24 and 5/2/24. Those who completed the study were paid $25. During each visit, users filled out a Google Form (text of the form captured below) which prompted them to tell the story of their visit, what they were doing before arriving on the floor, why they were there, what seat they chose, the specific activities completed, what they were planning to do next, etc.

Limited Data, Limited Conclusions

This study captured 21 different visits to the floor captured by 7 different people. Data from the study was limited and not meant to be representative of the population who use the floor. With this in mind, I intentionally reported out on the data as a snapshot of user behavior as opposed to findings that describe a population in general. This is important. To me it is the difference between user experience research and more traditional assessment. User experience research data like this helps generate ideas about service improvements. Often what we learn as UX researchers might inspire more questions or give us ideas about changes we could pilot to improve user experience. Service changes aren’t meant to solve every problem or be an intervention with a population-wide impact. As a UX researcher, it is important to me that the formation of a study matches the conclusions drawn from the data collected. If the study is planned to be limited, the conclusions that can be drawn from it should in turn be limited and not overly relied on as fact. It is still worth doing limited studies as they open doors into understanding (and in this case, helped us as library staff more visually understand and document what studying on the floor can be like), but insights gained are not meant to be conclusions. In this instance, data from this limited study was combined with more comprehensive survey data that allowed us to document more statistical findings.

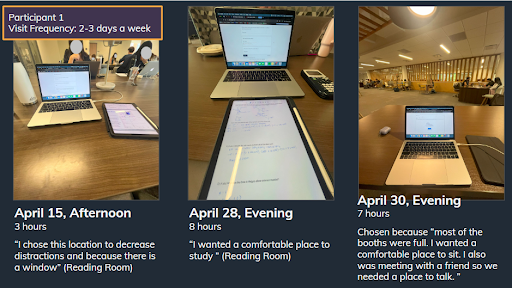

Photos of some of the data captured in this study. These photos show Participant 1’s three different visits during an afternoon and two evenings. Under each photo is a description of why they chose that location, such as moving away from distractions or finding a comfortable spot. See more data in this slideshow.

With all of that being said, here is a summary of the information captured in the study:

- Study space choice - participants chose their study space on the floor based on noise level, availability, lighting, type of activity, meeting up with friends, etc. Multiple entries describe visits where participants were sitting in a location that wouldn’t have been their first choice.

- Different spaces for different activities, same people - this could look like focusing and being productive in the quiet reading room on one day, needing the right noise level to work with friends on another day.

- Different visit lengths - the data includes descriptions of visits as short as 30 minutes to an hour and as long as 8 hours.

- Frequency of use - each of the 7 participants reported using the floor at a different rate of frequency. The highest was everyday, the lowest, once or twice a semester.

- More on what “doing work” or “studying” actually means - participants were asked to describe in detail what they did during their visit. This elicited answers like “I worked on a lab report for my biomechanics class as well as a presentation for my biomechanics class. I also completed a practice exam for medical terminology.” This information coupled with where they chose to study gives us more information about what our study environments help students accomplish.

- Photos of the floor - by requiring participants to take their own photos, we are able to capture observations of the floor without collecting that information in more invasive ways as researchers that could be interpreted as surveillance.

- Capturing in-between moments, social and solo atmosphere of the floor - participants were asked to mention if they interacted with anyone during their visit. This question captured things like running into friends, club members or classmates, or saying hello and chit chatting before doing work. It also captured how students often study with friends, sometimes working on the same thing, other times just sitting near each other and doing their own work. At the same time, the study captures multiple solo visits as well.

Conclusions

Assessing spaces is complex. From my perspective, the process is very time intensive, and there are so many variables at play in a space that it can be very difficult to sort out key findings (if you can actually make any with confidence). Mixing methods and combining data points to tell the story of a space while also identifying trends is what has felt most effective to me. Through these two studies and the additional attitudinal data collection methods not discussed in detail here, we were able to reflect on the design goals for the floor, what seems to be working, and where there are opportunities for some improvement. The takeaways we uncovered point to ways the library could consider undertaking future space renovations which we hope the success of this floor will inspire.