Introduction

The University of Michigan Library boasts one of the largest public university library collections in the world, with nearly 15 million volumes available in the system. Users of the University of Michigan Library, whether they access the collection on campus or through a computer screen, face the task of sifting through catalog records to find and discover the materials they need. For users searching for non-English language materials, this task can be challenging.

Some searches fare better in Library Catalog Search than others. In Spring 2021, while analyzing data from a survey of satisfaction on Library Catalog Search, my supervisor Robyn Ness, senior user experience strategist, and I noticed that users searching for non-English materials seemed to struggle to find items more frequently than those seeking items in English.

In conversations with colleagues in the Asia Library, we learned of specific examples in which they had experienced challenges finding materials in Chinese, Japanese, and Korean. The project subsequently unfolded.

The goal of the project, in short, was to conduct exploratory research to better understand both how our users interact with Library Catalog Search to locate and discover non-English materials, and where those users encountered challenges. More specifically, we hoped that this project would give us some insight into the specific linguistic and metadata divergence and system design choices that create or exacerbate obstacles for our catalog users.

As we began our explorations in Library Catalog Search use, we wanted to know the following:

- What is the current process or behavior for users searching for non-English materials?

- Are there any divergences between the language the user is searching in and English that leads to difficulties with the interface?

What we did

In order to go about answering these questions, we interviewed frequent Library Catalog Search users who regularly search for non-English materials. Robyn conducted three pilot interviews in the Spring of 2021, and I conducted eleven interviews with faculty, staff, and students throughout the summer. Our goal was to find a diverse group of participants to ensure that this research presented as many viewpoints as possible. In the end fourteen participants, made up of catalogers, subject librarians, and students, were included in the study.

Through semi-structured and informal interviews, I asked participants to share their screen, walk me through a recent search, and point out any challenges they regularly encountered within the interface. Participants were free to share any examples, challenges, ideas, or impressions they wished to share without being prompted. This style of interviewing meant our conversations were sometimes non-linear and diverged from the intended questions, but also rewarded us with a plethora of information about users’ preferences, interests, and frustrations. It also meant that we gained insight into a number of external tools, use cases, and challenges that we hadn’t originally planned to discuss!

What we found

These interviews provided us with hundreds of observations and insights from participants on various obstacles users encounter when conducting non-English searches in Library Catalog Search. While these observations were numerous and varied, here we will discuss three specific types of linguistic differences which cause several of the most significant issues:

- Grammatical structures

- Writing and date conventions

- Naming conventions

I will describe the nature of these differences, and offer some examples which were shared with me throughout the interviews, below. It does bear noting, however, that I conducted these interviews between June and August 2021. As such, many of the issues shown in the examples below have since been resolved by the library’s fabulous tech team. I reproduce them here not to indicate that they are still an issue, but rather to illustrate the type of problems participants described.

Grammatical structures

The first, most complicated, and perhaps one of the most important insights which came out of this research is the fact that the grammatical structures of languages other than English are sometimes incompatible with Library Catalog Search features.

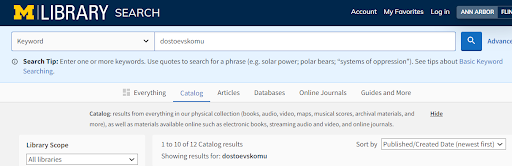

An example of differing grammatical structures comes from a search for Russian materials. As a case-based language, nouns take on different endings to communicate their role in a sentence. In the example below, Dostoevskomu is a variation of Dostoevsky in the grammatical dative case, meaning it is an indirect object used with certain prepositions. In this instance it could be roughly translated to “back to Dostoevsky.” The image below shows that a search for Dostoevskomu in Library Catalog Search returns twelve results.

Meanwhile, a search for the more widely-known and used term Dostoevsky returns 966 catalog results.

![[A Library Catalog Search for the term 'dostoevsky' returns 966 results.]](/sites/default/files/blogs/tinystudies/non-english_catalog_search_dostoevsky.png)

Writing and date conventions

Grammatical structures aren’t the only source of frustration, however. In some cases, different writing conventions can lead to search difficulty. A primary example of this is the fact that the Chinese language has multiple alphabets: traditional and simplified. A user searching for Chinese materials within Library Catalog Search must then conduct two separate searches, one using traditional characters and one using simplified characters, in order to be sure they see all relevant results.

Additionally, written Korean sometimes uses Chinese characters. While this in and of itself doesn’t always cause substantial issues, the Chinese characters can then be used for Korean author headings in place of Korean characters. A user searching for a Korean author using Korean characters might then be unable to find the correct heading or materials.

Finally, in some cases different calendars are utilized by publishers which can cause difficulty locating recently published materials or properly sorting search results. One example was the fact that some items within the Library Catalog utilize the Hebrew calendar to record publication dates. Because of this, if a user searches for materials in Hebrew and sorts the results to see the newest materials first, the first result has a listed publication date of 5763…

![[A Library Catalog Search results page shows results for the query 'moses,' sorted by Published/Created Date (newest first). The first item in the results list is an item written in Hebrew with a listed Published/Created date of 5763.]](/sites/default/files/blogs/tinystudies/non-english_catalog_search_hebrew_date.png)

…even though in the Gregorian calendar 5763 corresponds with the year 2002.

Naming conventions

The third and final major difference we revealed is a difference in naming conventions across cultures. These differing naming conventions can make it difficult for users to locate or discover works by specific authors, especially if the names don’t follow the Surname, Firstname structure typically used in English library systems.

One example of this comes from Spanish language materials, in which authors often have two last names, such as Federico García Lorca. While users may know the full name of an author whose work they are seeking, these names often are not cataloged consistently, which can lead to users missing potentially relevant results.

Multiple surnames aren’t the only instance in which naming conventions can cause frustration for users. Another example comes from Persian and Urdu, in which names often can appear as either one word or two, an ambiguity which can make it difficult to achieve search precision.

In the example below, searching the surname Shafikadkani as a single word returns no results.

![[The Library Catalog Search for the term 'shafikadkani' as one word returns no results.]](/sites/default/files/blogs/tinystudies/non-english_catalog_search_shafikadkani.png)

Meanwhile, searching for the same surname as two words returns two catalog results.

![[A Library Catalog Search for the term 'shafi kadkani' as two words returns two catalog results.]](/sites/default/files/blogs/tinystudies/non-english_catalog_search_shafi_kadkani.png)

As in all things, a more experienced user can, and likely does, have strategies and external tools to work around these discrepancies and find the materials they need. However, novice users likely do not have these strategies and tools to aid them in their search. For all types of users, the examples shown here can cause both frustration and confusion.

The good news

This study did reveal some areas in which the U-M Library catalog functions well and allows users to quickly locate the materials they are looking for. Participants mentioned that the University of Michigan is a leader in collecting vernacular works, and praised the library’s diverse, engaged staff who are available to help users find materials, even when the process is complicated.

Furthermore, users can adapt to complicated search conditions through the use of various Library Catalog Search features, Advanced Search, and external sources. Several participants mentioned they use sorting mechanisms and filters in Library Catalog Search in order to discover and locate materials. These features generally worked well for users, though there are opportunities to make these features more visible and to more explicitly communicate to users what they do. Other participants discussed external tools they used to help them refine or verify search results; WorldCat and the Library of Congress were two frequently cited interfaces, as were national libraries of various countries and digital transliteration tools such as translitteration.com. All of these tools and workarounds not only gave us insight as to how users typically work within Library Catalog Search, but also where Library Catalog Search fits into their greater research environments.

Looking forward

One of the most exciting, and in some ways most frustrating, aspects of this study is that it led to few concrete conclusions. The findings gave us a much more comprehensive understanding not only of the types of challenges encountered by users, but also of the critical differences or design choices which caused or exacerbated them. Yet at the conclusion of each interview, and again as I sorted through all the data, it became clear that the more I learned the more questions I had. We received answers to the original research questions we articulated before beginning, yes. But those answers were as varied and multi-faceted as the individuals who provided them, and any single interview could have been the basis of a study all its own.

The exploratory nature of the study meant we had the opportunity to talk to a variety of people representing both different areas of the U-M Library as well as different linguistic families. This variety in participants led to some truly engaging and insightful conversations; as a researcher, I learned more than I had hoped to about different languages’ grammatical structures and individuals’ search processes within Library Catalog Search. Listening to experienced professionals discuss their research and professional work, while also patiently explaining grammatical points with which I was unfamiliar, was a highlight of this project for me; the breadth and depth of the feedback we received was astounding.

The differences in grammatical structures, writing conventions, and naming conventions discussed above are by no means exhaustive. We chose to highlight the examples included here as we believe they showcase the various ways in which the Library Catalog Search interface can cause frustration for users. Having said that, it must be acknowledged that there are undoubtedly scores of experiences and specific examples which would add depth to the study and which were excluded either by our choice in participants or by our analysis methods. Participants offered several sharp observations which we did not include in this list of findings, and some of the most valuable feedback we received was suggestions as to where and how we could conduct further research. Furthermore, there are a number of distinctions which can, and in the future should, be made regarding the languages represented here. These distinctions both shade and complicate these high-level findings, but offer a level of specificity which was outside the limits of this particular study.

With this in mind, it is no surprise that many of the findings from this study do not lend themselves directly to actionable recommendations, but rather give way to more focused, specific questions. As we move forward into the summer months, carrying with us these observations and insights gained from this study, our hope is to use these findings to inform subsequent projects and shape future questions.

The findings help to deepen our awareness of and appreciation for the scope of the University of Michigan Library catalog, as well as the complexity of the needs and preferences of its users. But their greatest value may be the way in which they encourage us to look closer, to ask more questions, to dig deeper. We are just at the beginning of this research, and while we are excited by the findings uncovered in these interviews, there is still much work to do in order to more fully understand the consequences of our design decisions and how to mitigate user frustration. These findings, and the questions they raise, can help to guide future research.