Background

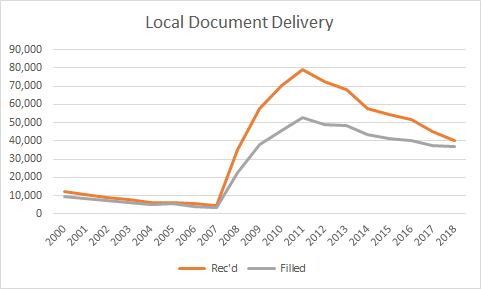

Document Delivery provides a two-pronged service for patrons on campus: the traditional Interlibrary Loan Borrowing service, and a scanning and delivery service for books and articles from material that is owned by the University of Michigan Library. The service for material held locally is now called Local Document Delivery (previously 7FAST). Since its creation in 1980, the Local Document Delivery service has sometimes been provided free of charge and sometimes for a fee, depending mainly on the library’s budget strategy. In 2007, free Local Document Delivery for faculty and graduate students was piloted, and request volume skyrocketed from under 5,000 requests received to 60,000 requests received in the first year.

(request volume in Local Document Delivery, 2000-2018)

The increase in Local Document Delivery fed a 25% increase in Interlibrary Loan Borrowing (requests to other institutions) as well (for example, when material we owned was checked out). Meanwhile, unrelated decisions in other areas of the Library increased Interlibrary Loan Lending requests by 400%. The entire department was drowning in production work with tight turn-around times (in Document Delivery, we measure the time elapsed from the moment a patron places a request to the moment of notifying a patron that the request is available).

Even while departmental staff members struggled to keep up with request volume, we were concerned that two major patron groups still had to pay a fee for the Local Document Delivery: undergraduate students and university staff. Questions of equity aside, having a dual service model presented a number of challenges for not just the staff in Document Delivery, but for staff throughout the entire library as they struggled to explain the difference in services and service levels. Library patrons were similarly confused and often frustrated, requiring a great deal of customer service support. Maintaining separate sets of web pages and processes for fee and free services made the department less agile. Further, keeping an incredibly complicated financial process in order for what amounted to less than $100 of transactions a month was costly.

The departmental managers wondered: What would happen if we made service free for staff and undergraduate students as well? While the department had known that more staffing would be requisite and had planned accordingly, there were unanticipated consequences to the dramatic increase in request numbers. For example, processes that were fine for 5,000 requests a year broke down with 60,000 requests, despite staffing increases. Processes had to be broken down into more and more granular steps. Our document delivery specialists became even more specialized. We turned knowledge work into assembly line-style knowledge work. While this was a great step forward in handling the workload, it meant that no single staff member would see a single request through from start to finish, and the birds-eye view would be unattainable. As a result, adding a simple step at the beginning of a request’s life to ease one part of the process could have a ripple effect down the production line and create bottlenecks. Further, processes requiring zero error rates could break down completely. In one memorable example: we discovered our delivery labels were no longer reliably printing addresses. One lengthy troubleshooting period later, we realized that the logic that allowed the delivery address to be pulled from the database was case-dependent, and new staff were not trained to capitalize data in the key field. While we were able to adjust the logic rather than rely on constant vigilance, it’s a key example of the kind of problem we encountered.

Departmental managers had to become ruthless about evaluation of processes as a result, and we knew we could not support any changes to our service that would lead to sudden increases of 25%, 400% or 1300% again. Everyone in the department and above was extremely wary of making the Local Document Delivery service free for staff and undergraduate students.

Data and Findings

Using monthly and annually collected data from our systems on number of requests received and filled and similar metrics (easily broken out by the status (grad/undergrad/staff/faculty) of the requester), as well a variety of time studies that allowed us to create production benchmarks within the department, we regularly assess our workload, our average turn-around times, and cost of fulfilling items in both staff time and overhead.

We thought staff usage of Local Document Delivery would be low. The 2011 university staff usage of document delivery amounted to 1,441 requests (about 3% of our total requests). Even if total university staff usage increased seven-fold (the equivalent of the grad/faculty increase in 2007 after eliminating the service charge), we would experience an increase to about 10,087 requests a year (28 requests a day), an amount of work easily absorbed in a department of our size (essentially, this is slightly over one more request per person in the department.)

However, even with over 33,000 staff members at the University of Michigan, we did not think staff demand would increase much. For one thing, Interlibrary Loan had been free to university staff all along, and yet only 7% of Interlibrary Loan Borrowing requests came from staff patrons — hardly a lion’s share of the requests. Fortunately, a test-case presented itself in 2012 when we were asked to pilot a free Local Document Delivery option for the nursing staff. The nursing staff placed approximately three requests a month, an unthreatening volume. This looked very promising, as it suggested we could expect even lower numbers than we anticipated from our analysis. And indeed, when we were green-lighted to make Local Document Delivery free for university staff in FY13, staff requests rose to 4% of our total from 3%.

But the best outcome was that the use of a convoluted proxy process fell by half, and we saved hours of our staff’s time and increased the goodwill of our patrons who no longer had to use proxy accounts.

The remaining proxy users were mostly undergraduate students working on behalf of faculty, as it happened, which is where we turned our focus next. Most undergraduate requests for Local Document Delivery were placed by accident, and we rarely fulfilled two requests a month. We could extrapolate from how many Interlibrary Loan Borrowing requests came from undergraduates, but we also subscribed to the common academic library belief that most undergraduates are not looking for specific articles and books, as with graduate students and faculty, but rather seek solid sources of information that they can get quickly to complete short-term assignments. Better the article you can get today that has good information than the perfect article you might receive in two days. Interlibrary Loan Borrowing would not then be a good gamble for most undergraduates. But would they consider Local Document Delivery to be an enticing option?

No test case presented itself, but with Local Document Delivery request volume slowly decreasing over time (for a variety of reasons, from social media article-sharing among patrons, to the steady purchase of electronic journal backfiles by the University Library), we made a leap of faith to eliminate the fees for undergraduate requests. This created a fully seamless entry point into Document Delivery for all patrons, eliminated virtually all need for proxy accounts, and greatly reduced financial complications in the department.

Undergraduate requests increased 413% — from 123 requests in 2017 to 631 in 2018 (from .5 requests per day to 2.5 requests per day). This presents a minor increase in workload for us, but we believe it has eliminated a lot of confusion and annoyance for the undergraduate students who use our services.

Using our existing systems to analyze available metrics and data points in an ongoing way, we were able to make our Local Document Delivery services free for all patron categories. Making significant service changes created opportunities for leaps forward in thinking about the patron experience and simplified workflows, as well as for our participation in the statewide library consortium (MeLCat) as a lender, and for our enhanced scanning services for patrons with print disabilities.