where violence flows

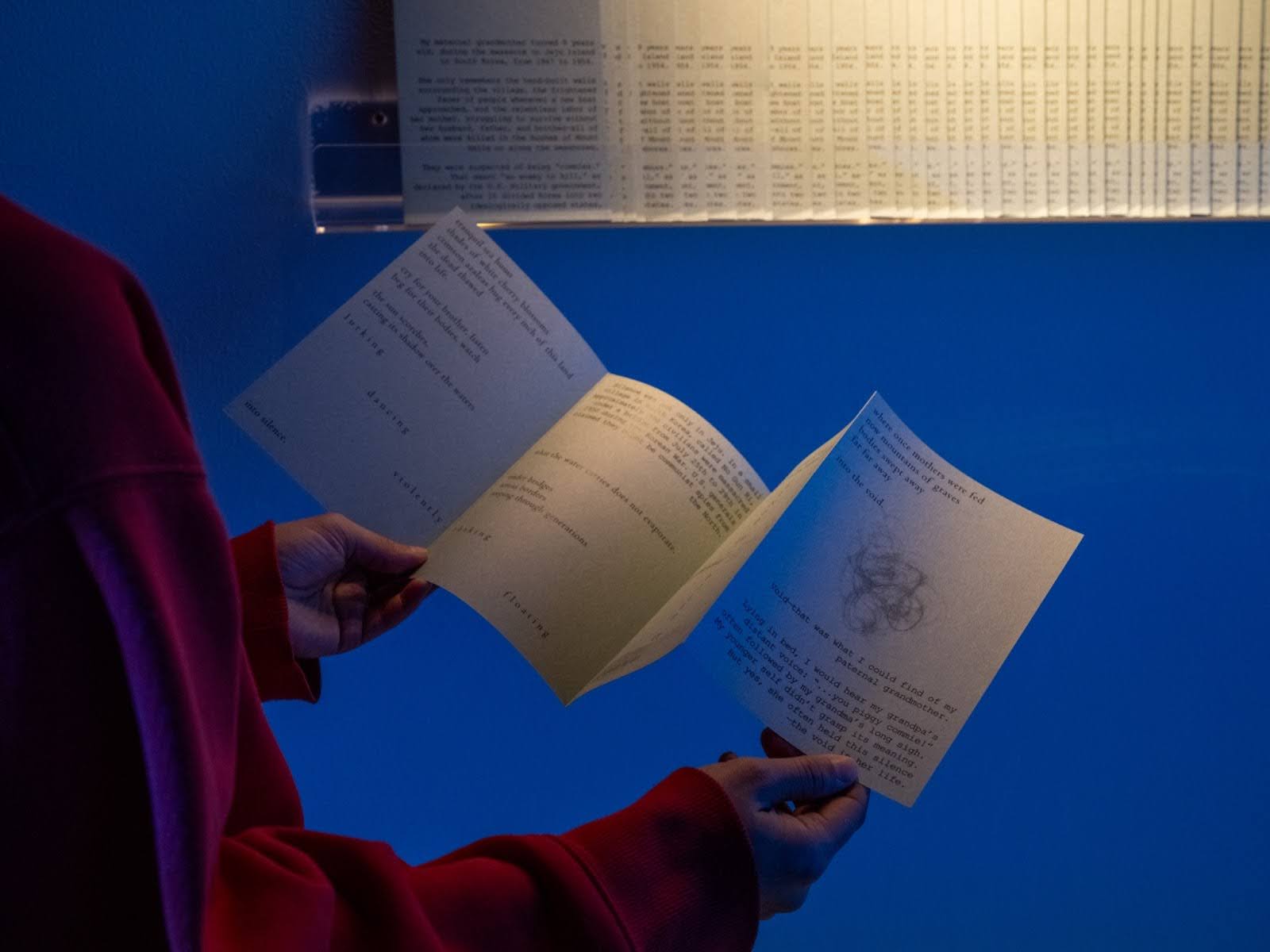

Installation View of where violence flows (2025), Photo by Andy Kajie

This spring, I presented a collaborative zine project titled where violence flows at my thesis exhibition In Flow, held at Stamps Gallery in Ann Arbor, Michigan, from March 22 to April 12, 2025. Created in collaboration with poet Kyunghee Kim and Matt Dhillon, the zine is a meditation on familial memory, inherited grief, and the enduring marks of U.S. imperialist violence on the Korean Peninsula. This project was deeply personal—and collective. Through a support from Library Mini Grant, we were able to unveil and share the silenced narratives of war and massacre.

A Landscape of Silence

The zine is informed by the stories of my maternal and paternal grandmothers—or by what remains of them.

During the Jeju 4.3 Massacre, my maternal grandmother turned nine years old. Between 1947 and 1954, tens of thousands of Jeju islanders were killed in a brutal counterinsurgency operation approved by the U.S. military government. My grandmother didn’t speak of the violence directly, but in fragments—memories of stone walls around the village, of faces turning pale when new boats arrived, of her mother’s aching silence after losing a husband, a father, and a brother in the bushes of Mount Halla and the sea. These stories haunted the edges of her language, surfacing in gestures, pauses, the work of surviving.

We carried these fragments into the writing process. As Kyunghee composed poems that wove together reflections on the landscapes of Jeju Island and the bodies buried beneath them, I wrote essays about my grandmothers—women who lived through the violence—and the lineage of those tragedies carried in my body. As we found: “what the water carries does not evaporate / under bridges / across borders / seeping through generations.”

A River of Voids

While Jeju’s massacre left behind a legacy of silence, shame, and denial, it was not the only site of violence in Korea. In 1950, in the early months of the Korean War, approximately 300 civilians—mostly women and children—were killed by U.S. forces under a bridge in No Gun Ri, suspected of being communist spies from the North.

The number 300 became more than a statistic. We printed exactly 300 copies, echoing both the death toll and the lingering presence of the unaccounted-for. Each zine was printed on soft, plant-fiber paper—designed to evoke the porousness of memory, the flow of water, and the fragility of bodies.

The reflection of the Korean War leads to the next chapter about my paternal grandmother. As a refugee from Hwanghae, a region in North Korea, she is assumed to have fled south during the war. The wounds she carried were something less visible but more embodied. I remember her through her silences: the long sighs following my grandfather’s sharp words, untold stories, and unresolved questions after her passing in 2023.

“She once tried to throw herself into the Han River,” my aunt once told me, indifferently. What was she hoping to forget—or to join? Her stories of death and survival remain silenced underwater, flowing through rivers, oceans, streams—and swallowing me, here and now. This feeling shaped the final section of the zine. A voice (perhaps mine) ask:

“Are you here with me? Are we submerged?”

The question lingers in water, still unresolved.

Nonlinear Flow

The zine is not chronological. It doesn’t list histories linearly, because memory doesn’t work in that way. Instead, it moves like a tide—rising, breaking, pooling. Poems overlap with prose. Lines drift apart into vertical cascades of words. Two distinct voices—a poem and a narrative—seem to converse, echoing and reflecting one another. Moments of softness, like the quiet murmurs of “...bodies swept away / far far away” are followed by sharpness—like the indictment, “white are the heroes / north are the enemies / we are taught.”

We wanted the reading experience to feel immersive and destabilizing—like wading through water that suddenly deepens. Its leads audience to the end of the poem: “we will swim the waters of jeju / dipping, gliding / along the han river / toward the han river / towards mount halla / against the current, we dance / breathless / below the bridge of no return / gasping / and if we’re lucky / there may be our beginning.”

Distribution of Memories

At the exhibition, over 250 zines were distributed. Visitors often lingered over them—some carried them in the gallery to read; others carried them outside, to their everyday lives. We often had a conversation about how printed materials can become vessels of memories and mourning.

Each copy becomes part of the circulation of unspeakable histories—some read, some intuited, many forgotten. These stories are carried by readers into new contexts, beyond the exhibition walls.

Support Along the Way

Throughout this project, I received generous support through my consultations with the University of Michigan Library. Librarian Jamie Vander Broek guided me toward archival and theoretical texts that deepened my understanding of feminist performance art, post-colonial memory work, and ritual as a framework for art practice. These resources offered theoretical grounding and poetic provocations.

What Comes Next

I’m currently applying to other exhibition opportunities to continue sharing these themes—particularly in relation to militarized imperialist violence in the trans-Pacific and the intersections of poetry and visual language.

This project has reminded me that silence is not empty—it is full of tension, holding breath, bearing witness to what cannot be said. Silence can be read, marked, and answered.

As we wrote, printed, and distributed this zine, I kept returning to the image of my grandmothers—one laboring along Jeju’s shores, the other vanishing into the Han River. They both carry unspeakable stories. This work tries to swim back to them—not to rescue, not to resolve, but to meet them mid-stream—in the flow.

Installation View of where violence flows (2025), Photo by Andy Kajie

Acknowledgments:

I want to thank Kyunghee Kim and Matt Dhillon for their generous collaboration, the staff at Stamps Gallery for their support during the exhibition, and the University of Michigan Library and ArtsEngine for funding my production. Most of all, I thank the audience—those who sat with our words, carried our zine into the world, and allowed these stories to ripple out.

A video of the exhibition can be found here or viewed below.