Gender is a powerful social category that individuals constantly use to make sense of both themselves and those around them. The Western world splits people into two categories: woman and man. These two gender categories can be used to visually sort almost all things. Individuals constantly attribute masculinity of femininity not only to people, but to animals and objects, too. With this in mind, my thesis hoped to examine how individuals interpret the gender cues that others present, particularly those present in the face. Individuals who identify outside of the man-woman dichotomy are gaining increased visibility. The core question is how has the increasing visibility of the nonbinary community begun to change how people conceptualize gender, particularly in how they perceive the gender of others?

People use their unconscious beliefs about gender to gain insight into the personalities of the people they meet. For example, based on knowing someone is a woman, one might infer that she wears make-up, cares about kids, and loves TV shows like The Bachelor. Knowing someone is a man, one might infer that he likes sports, loves cars, and enjoys lifting weights. But what about people that exist in the “space between” woman and man? Does the current gender order allow individuals to make inferences about people who perform a nonbinary gender?

Gender’s omnirelevance makes it an important area of study, but simultaneously renders it an unquestioned given for much of the general populace. When making gender attributions, individuals rely most heavily on the body to make their unconscious decisions. The way someone perceives and interprets different gender cues (among other social categories) influences how they sort others into cultural gender categories; this is known as the gender attribution process. In Western society, one’s biology (e.g., genitals) is the ultimate determinant of gender. In order to be read as a “valid” gender – man or woman in the U.S. – individuals must present themselves in ways that align with the dominant view of their gender. This presentation must be coherent; it must be recognizable as the target gender in order to be valid.

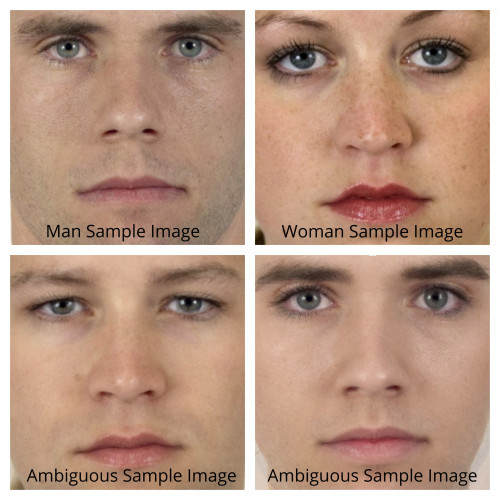

The studies I conducted focused particularly on how people perceive the gender of faces. People recognize faces quickly and efficiently, and individuals are quick to assume the gender identity of others based on facial features. Previous research looking at how individuals perceive gender fails to consider the very real possibility of a third/nonbinary gender attribution. Almost all prior studies on facial gender perception do not give participants the option to attribute gender outside of the binary; they only examine attributions of woman and man. Even when the focus is on ambiguous genders, researchers focused not on the implication of an attribution outside of “man” and “woman,” but instead on how an ambiguous attribution becomes an attribution of “man” or “woman.” In an attempt to fill this gap, this research will focus on if and when people make nonbinary attributions and look at cognitive representations of those nonbinary genders.

My thesis explores whether specific facial features are utilized when perceiving gender cues and examines the attributional distinction that the average person makes between who is a man, who is a woman, and who is nonbinary. This research will, hopefully, provide not only a greater understanding of the shifting Western gender ideology and the gender attribution process, but also create a foundation upon which further research can be built.

Study 1

In Study 1, I examined how individuals attribute gender to others’ faces. A face morphing task was performed by the participants to illuminate the attributional gap between man and woman. I hypothesized that participants would categorize more faces as “men” than as “women.” Prior research supports the notion that “man” acts as the normative baseline for gender, implying that ambiguously gendered faces will be interpreted as men.

Study 2

Study 2 followed-up on the findings of Study 1. Study 1 showed that some faces are ambiguously gendered, but did not investigate whether that ambiguity led to an ambiguous or otherwise nonbinary categorization. Study 2 provided space for participants to attribute either man, woman, or another gender to the ambiguous faces. Thus, I was able to examine the relationship between nonbinary gender attributions and perception of ambiguity. Participants rated faces found to be ambiguous in Study 1 as either a man, a woman or another gender. I hypothesized that most participants would assign a binary gender to the ambiguous faces, but that there would be a small subset of the population that would use the label of another gender. Forcing participants to attribute a gender to each stand-alone face, while providing space for an attribution outside of the man-woman dichotomy, allows us to examine whether individuals are conceptualizing gender as being more fluid and expansive than the dominant binary model. Given that the Western gender ideology relies on binary thinking, I assumed that the average person would sort facial stimuli primarily into the categories of man or woman. Individuals who have been exposed to nonbinary or other non-conforming gender presentations would, assumedly, have less essentialist beliefs and thus be more open to using a gender category outside of the man-woman dichotomy.

General Results:

My research shows that people do in fact attribute genders outside of the man-woman dichotomy in certain contexts. Much previous theory surrounding gender centers the Western gender ideology that says there are only two genders and those genders are man and woman. This series of studies shows that that may no longer universally be the case; some people are able to categorically recognize nonbinary genders in others. It seems that some individuals have begun conceptualizing gender in a less restrictive way than previous generations. The studies herein utilized an MTurk sample, which is predominantly white and cisgender, but future studies should explore this phenomenon within different demographic groups – how would a non-cisgender (e.g. individuals who do not identify with the sex they were assigned at birth) population attribute gender to ambiguous stimuli? Is there a geographic difference in that urban individuals have more fluid conceptions of gender than rural individuals? How does religious identification influence one’s propensity to attribute a gender other than man or woman?

Of further interest is how ambiguity is perceived differently between Study 1 and Study 2. In Study 1, when lacking a nonbinary gender label, I found a significant number of faces that were attributed both man and woman at chance rates (i.e. some faces were attributed man and woman at equal rates – their gender was hard to reliably determine). In Study 2, which used the faces from Study 1 mentioned above, participants were confidently making decisions about which of these faces were men and women and, for many of the faces, there was participant agreeance on which gender category each face belonged to. It seems that, when asked to attribute gender to a standalone face, ambiguity begins to fade. This begs the question: are people truly seeing less ambiguity or are they convinced that the ambiguity must be either a man or a woman and choosing the “best fit”? Why does ambiguity, in the majority of contexts, fail to lead to an ambiguous or otherwise nonbinary attribution?

My research provides evidence that nonbinary or otherwise ambiguous genders are perceivable. This has implications not only for perception processes - what aspects of gender expression are salient when attributing nonbinary to another individual? – but also for gender theory more broadly. Clearly, the man-woman binary is no longer the sole working model of gender within Western thought. As this two-and-only-two framework continues to break down, will individuals still be able to make inferences about other’s personality, interests, and the like based on their gender expression? Will we see a decrease in the importance of the genitals when it comes to gender attributions? There are even implications for gender role theory here: as nonbinary genders become categorically unique, what actions will become indicative of a nonbinary gender? What professional and domestic roles will those that occupy nonbinary spaces inhabit? The studies herein are merely a stepping stone into the unknown and much future research is needed to even begin to flesh out the phenomena being captured.

Fund Allocation:

I used the Library Mini-Grant funds to purchase stimulus design tools, statistical analysis software, and pay participants for their time. I used Morpheus – and photo morphing software – to create the faces used in both studies. I used SPSS to perform my analysis of the data. The studies utilized an online MTurk sample, and individuals were paid the equivalent of a $10/hour wage when taking my surveys.

Next Steps and Library Mentor

My library mentor, Hailey Mooney, was incredibly helpful in terms of fleshing out my literature review for my project. She educated me on how to best use the library search features and how to use search phrases most efficiently.

Going forward, I hope to continue performing research along this same vein. My thesis may have answered one question (Do people ever attribute gender outside of the man-woman dichotomy? Yes, they do.), but it’s opened the door to so many others that still need to be empirically investigated.