The Project

An 1861 map of New York City, now worn with age, the delicate paper permanently creased from its life in a file-folder, shows the familiar landscape of upper Manhattan. Two hand-drawn lines, remnants of its previous handling, cross the page – a red line runs along sixth avenue, and a yellow one cuts across 86th Street, intersecting just below the reservoir. Aside from a few cosmetic changes - “Bloomingdale Road” has been straightened out into Broadway, the Great Lawn is now decorated with baseball fields – much of this landscape, detailed over a century ago, remains today. For over a century, millions of people have traversed these same paths, unknowingly following each other through the unremarkable progression of days and years.

I came across this map in the papers of Ignatz Anton Pilát, the Austrian botanist who became the first landscape gardener of Central Park, which are housed at the New York Public Library’s gleaming Schwartzman Building on 42nd Street. Pilát was chosen by park architects Frederick Law Olmsted and Calvert Vaux with designing the park’s foliage. He was also tasked with designing the Ramble, the woodland area between 66th and 79th Streets.

Olmsted and Vaux imagined the Ramble as a “wild garden” – a series of winding paths designed for aimless wandering, a manufactured area of natural seclusion in the midst of the city. The other thing about the Ramble it has become a gay landmark. Throughout 20th century, it was a well-known and popular site for cruising, its hidden pathways and secluded woodlands serving as a perfect site for private, often anonymous, sex. There is much more to the Ramble, though – it was a refuge, a place of solace, for finding community in a city where that community was not yet visible, a place to be alone together.

I was there, at the NYPL, because I had chosen the Ramble as the topic for my next project – a project which I am grateful was supported by the U-M Libraries Mini-Grant program, which funded this research trip. I had recently done a similar project for the 50th anniversary of the Stonewall Riots, a piece that was commissioned by a church literally around the corner from Stonewall, and wanted to play around with writing more pieces related to queer life. For this project, I was as intrigued by the significance of the Ramble in New York’s queer history as well as the ideas behind its design. Could there be something inherently queer about the idea of “planned wilds?” Of rambling? Isn’t a place defined by seclusion and shrouded pathways a physical realization of the closet? By digging up some dirt on the Ramble’s origins, I hoped to contextualize and illuminate its history.

In his essay “Ephemera as Evidence,” José Esteban Muñoz argues that the traces of queer acts –“those things that remain after a performance, a kind of evidence of what has transpired by certainly not the thing itself”– must be taken as evidence of queer lives. “Queerness,” Muñoz writes, “is often transmitted covertly,” which “has everything to do with the fact that leaving too much of a trace has often meant that the queer subject has left herself open to attack.” [1] When I first read this essay two years ago, in an undergrad performance studies seminar, I was searching, as I am still, for ways to find deeper meaning in my musical life, which too often seemed either pedantic to the point of being ineffective – I’m performing a piece about climate change! That will stop it! – or entirely unrelated, which is to say largely irrelevant, or relevant only to those, frankly, with the time and means to care. I was also really starting to figure out what queerness means to me – not just as a sexuality, but as a way of being in the world – and wanted a way to access this in my creative work. Muñoz offered a world-opening way in. By finding pieces of ephemera and using it for musical means – a diary entry as the text of a song cycle, for example, or pairing music with aged photographs – we could make these performances visible, where before, for the sake of survival, they left only a trace.

So I went to the archive, looking for traces. This was my strategy for the Stonewall piece as well. For that piece, I found a flyer – a flyer! like a random thing you’d find on a lamppost! – for the inaugural Pride parade, then called the Christopher Street Liberation Day Parade, which was put up by the GLF and held on the first anniversary of the Stonewall riots. I was obsessed with the idea that something so innocent and innocuous could actually be the perfect window into queer history. I set the text from this flyer to music.

This Ramble piece would be a bit trickier, I thought, because I was trying not just to represent a singular thing – like a place or event itself, but the idea of the thing, too. I knew I wanted the eventual piece to feel like rambling – if it was the form of the garden, it should be the form of the piece. I had vague thoughts about maybe using a text, if I could find the right one, and thought I might incorporate field recordings from the Ramble. But I had to find the right way in, which required giving into the process of discovery, waiting for something to strike you that you know is right. This is especially true for a composition project, wherein my criteria isn’t just information – which abounds – but something that will lend itself to music. You turn through piles of folders, some faster than others, leafing through yellowed paper and muted photographs until you find something salient. Archival research can and should feel a bit like rambling. There’s a peculiar and wonderful kinship between the two.

It was during this process that I saw the map, from 1861, a literal trace of the city as it was – evidence, as it were, of the people that made it alive, and a glimmer of possibility for what it would become. In the archive, we can commune, from a position of radical difference, with the bodies and lives of the past.

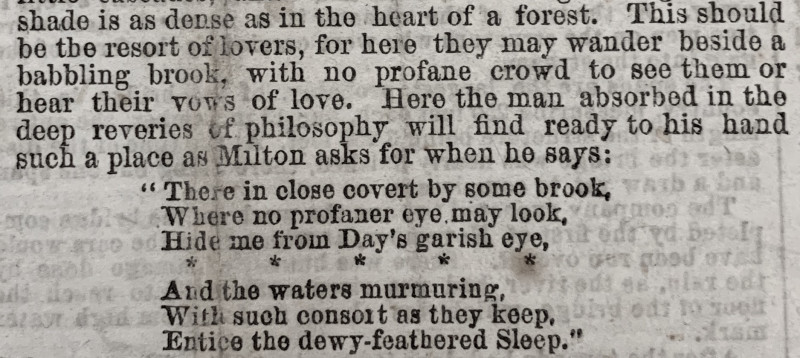

It was also during this process when, out of all the notebook entries and newspaper clippings I came across, I found what I knew immediately was the perfect text – an excerpt from an 1866 editorial in the Chicago Tribune (I had hoped it would be a New York paper, but this will do):

“Below the reservoir the ground is either level or gently undulating; above it, it breaks into hills, and presents such rugged features of natural scenery… Our park will grow each year more and more romantic and attractive, and more and more assume the appearance of a diversified natural landscape. Large as its area is, the designers have aimed to conceal its boundaries and convey to the visitor the idea of still larger extent… To shut out the city, or conceal the close proximity of neighboring roads, impenetrable thickets have been employed, and, to give perspective to minor parts, the shrubbery has been disposed in converging lines, and the groves so formed - with paulownias, platanas and maples in front, oaks, ashes and poplars next, and the light-colored and feathery-shaped locusts, silvery ables, or silver-leafed maples in the background - that one is cheated into the belief that he is looking over a wide stretch of country; while, with dexterous skill, vistas are opened through the trees wherever a view can be had of the shores or waters of the distant rivers… Leading along the western bank of the lake and the brook which will feed it, there is a path cut through a dense plantation of natural growth that every one should see, but few do. It passes by two charming little cascades, and where it runs through the grove the shade is as dense as in the heart of a forest. This should be the resort of lovers, for here they may wander beside a babbling brook, with no profane crowd to see them or hear their vows of love.”

Next Steps

Now, my final step in this project is to actually write the piece, which I anticipate will premiere sometime next year. I’m writing and composing now from my kitchen table, where I do all my work now that we all stay inside. While we’re all working from home, zooming into classes and meetings, the steady progression of people following people has come to rest. Watching New York City from quarantined safe haven, I see the rising death count every day, the growing list of bodies – friends of family, family of friends, and strangers - who once walked these same paths and no longer will. We thank frontline workers and talk to loved ones, staying six feet away but holding each other tight – finding solace in a time and place of radical separation, the resort of lovers in a socially-distanced age.

The time will come, we hope and know, when we can wander and ramble again, amongst friends as in the anonymous company of strangers. Until then, as before, we remain alone together.

[1] José Esteban Muñoz, “Ephemera as Evidence: Introductory Notes to Queer Acts,” in Women and Performance: A Journal of Feminist Theory 8 no. 2, 5-16.

Leonard Bopp is a Graduate Student in the School of Music, Theater, and Dance at the University of Michigan

All photographed materials are from the New York Public Library Archives