In a world ruled by technology and digital citizenship, we are constantly warned of the ramifications of publishing something online. We are told that what is on the internet is permanent, that we should be prepared to face the consequences of all we release into cyberspace.

There is some truth to the concept of a digital footprint. But in reality, what is online is constantly being changed or deleted, small actions that could shift the way we perceive information. Preserving what is contained within these sources grants a fuller picture of history.

A notable and often unconsidered quality of the internet is actually its impermanence — something that I hadn’t truly internalized until I started working on the Elections in Africa Web Collection project through the U-M Michigan Library Scholars Program.

As an International Studies and Romance Languages double-major — and someone with previous experience in digital studies — the project drew my immediate attention. In my French studies, I became fascinated by the dynamic character of African politics. Due to my prior research experience, I was also drawn to the exploration of technology as a tool for political engagement and transparency. I aspire to one day go into law, journalism, or research relating to the intersections of governance, communication, and communities; this project was the ideal opportunity to examine these concepts.

The project consisted of two parts. First, expanding the collection of archived websites on national elections in Africa by independently identifying relevant websites to be captured; second, archiving these websites by developing technical web collection skills. It would be a rich educational experience, allowing me to learn more about African political systems, parties, and actors while also instilling valuable knowledge of the Internet Archive’s Archive-It tool.

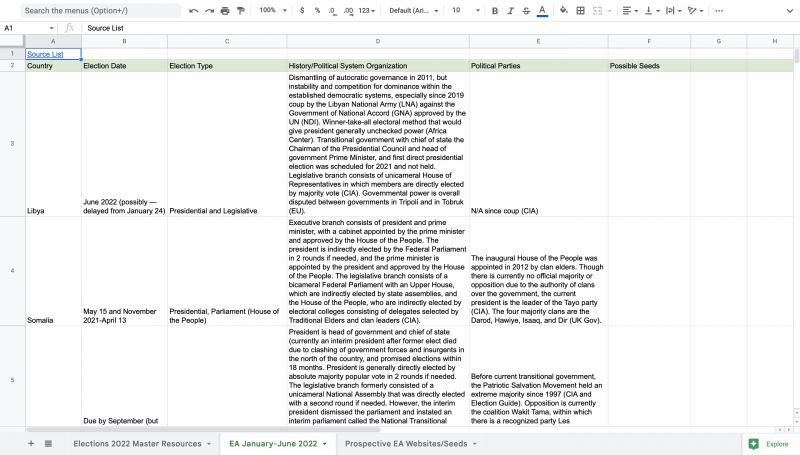

With help from collection creator, Loyd Mbabu, I determined which national elections in Africa were held from January through July 2022, and pinpointed important websites related to these elections. I used Google’s advanced search to explore different regional domains and languages, noting interesting websites from blogs, NGOs, electoral monitoring organizations, opposition parties, and official government websites. I searched for websites that held any important information about the political process or climate within the country of focus.

Screenshot of election details in spreadsheet

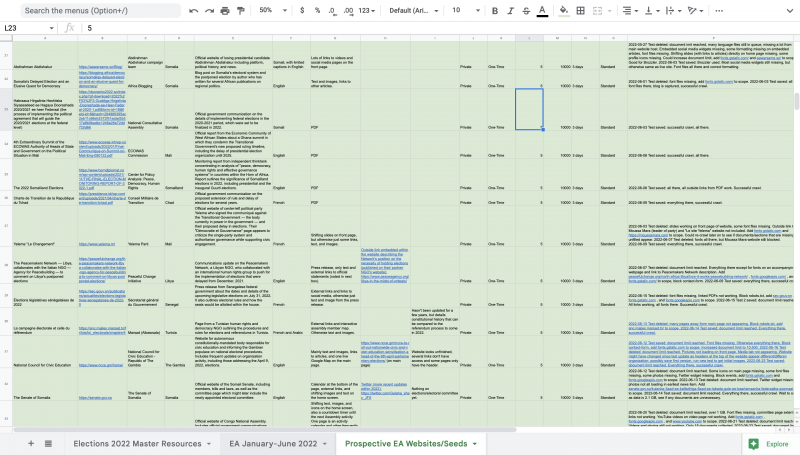

Once we had confirmed these websites — or seeds — I compiled them all into a shared Google spreadsheet and noted their metadata, including country, language, creator, and descriptions of the website content.

Screenshot of seed compilation and accompanying metadata details in spreadsheet

I then moved to the second phase of the project: web crawling with Archive-It. This tool collects all of the individual files from a website to produce a replication of the live site. The replication is accessible through a program called the Wayback Machine, and if you save the website, the copy will be stored permanently, even if the website is taken down.

My mentor, Scott Witmer, provided a comprehensive training in the functions and limitations of Archive-It. I read many documents and watched videos on the tool and analyzed my seed list to determine if any components might be more challenging to crawl; video, dynamic elements, and social media pages could all be obstacles for the crawler, or could use up our limited data.

I then set up my first test crawls and conducted quality assurance checks. This meant that after each crawl, I had to compare the captures to the live website. I noted whether there were any differences, determined which documents I had to manually input into the crawl scope, and then ran another test, sometimes several times.

The limitations of Archive-It and the specificity of each website meant that troubleshooting needed to be considered on a case-by-case basis. I quickly learned that each issue would involve independent research on possible solutions. I looked through Google searches, read through the U-M Archive-It documentation, or brought questions to my weekly consultations with Scott if I couldn’t find the answer on my own.

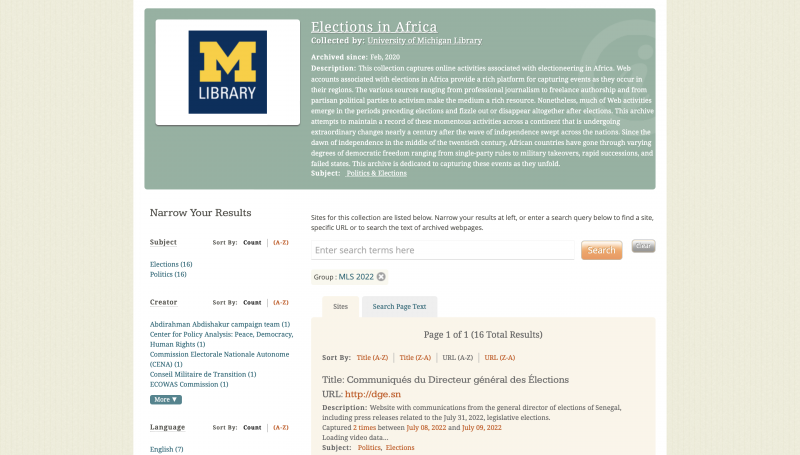

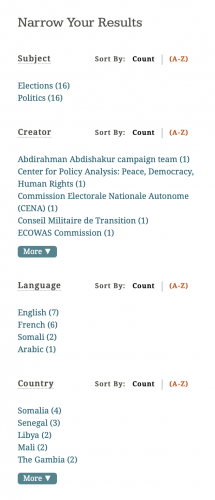

If I had a crawl that I couldn’t complete, Scott would remind me that sometimes an entirely successful capture of a website just isn’t possible with available tools. Researchers should always strive for complete replication, but when it cannot be achieved, even capturing 80 percent of its content will present most of the necessary information it contains about African democratic progress. Despite these obstacles, I was still able to save a significant number of successful crawls and make them public. In the end, I published 16 seeds to the U-M Collection Portal, all with associated metadata.

Elections in Africa Archive-It portal from summer 2022

Metadata groupings listed in Elections in Africa MLS 2022

Example of successful crawl in the Wayback Machine

As I waited for crawls to complete, I also learned about ethical considerations of web crawling, considerations that also apply to the academic research world as a whole: each researcher must recognize the bias involved in what content is archived and whether one should notify its creator about its preservation. Initiatives such as Documenting the Now aim to address these concerns and ensure that content is always saved in an ethical manner.

Throughout the course of the project, I developed a sense of my own project agency and managerial role. I made the content my own, honing my skills in independent research and leadership. I also learned how to set limits for myself upon entering a rabbit hole of information. I remained open-minded to going in different directions, to accepting the abandonment of a futile search.

I always process the impact of my work through what Scott and Loyd continually mentioned during our Friday meetings: I should always adjust my work to what would be most useful to future researchers. There was always an implication that what I was doing would certainly be used in future studies. I documented items that possibly won’t be present anywhere else in a few years. My work will offer posterity a more holistic view of political history — even if it’s through a single website.