Introduction

The impact of open access (OA) book publishing is usually expressed through quantitative metrics, especially ebook views and downloads. Indicators of qualitative engagement, such as citations and social sharing, are also metricized (e.g., citation counts, Altmetric scores) (see Figure 1). These numbers-based approaches do not reflect the human impact that happens when books are free to access and read. Secondhand anecdotes from authors are sometimes used to tell user stories, such as with the Author Success Stories on the OA Books Toolkit site. This study asked: “Are there ways to understand and represent the qualitative impact of OA on book publishing more directly?”

This analysis involved interviewing readers of OA books available on the University of Michigan’s open-source Fulcrum platform in the Lever Press and Big Ten Open Books collections. Lever Press is a publisher funded by a consortium of liberal arts institutions that publishes its books immediately open access. Big Ten Open Books is a multi-publisher collection of books from participating university presses at Big Ten Academic Alliance (BTAA) institutions. The Big Ten Open Books first collection, launched in August 2023, consists of 100 backlist titles on the theme of gender and sexuality studies. These were originally published under gated models but have been flipped to open access thanks to the support of the BTAA’s BIG Collection Initiative. The transcripts of reader interviews were systematically analyzed to reveal common themes using a qualitative methodology described below. I completed the study between January and April 2024, thanks to a Rackham Doctoral Intern Fellowship.

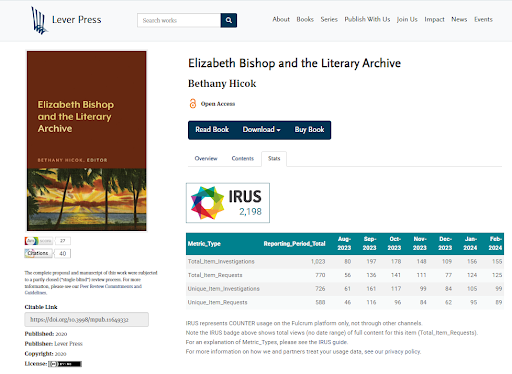

Figure 1: The impact of Elizabeth Bishop and the Literary Archive, published by Lever Press, is expressed through numbers. The IRUS widget displays usage (COUNTER total item requests since 2022), while the Altmetric.com “score” and Dimensions citations “count” express qualitative engagement but in quantified ways.

Methodology

My methodology for the study was partially based on an earlier and related study of a collection of University of Michigan Press OA books by my fellow doctoral candidate, Ani Bezirdzhyan (Bezirdzhyan 2024), and refined to fit these particular collections in consultation with Charles Watkinson (co-founder of the Fulcrum platform), Kate McCready (representing BTAA), and Sean Guynes (representing Lever Press). It was then submitted to the University of Michigan Institutional Research Board (IRB) and approved for an exemption (Study eResearch ID HUM00248606).

When a user opens a free book on Fulcrum, they are prompted to share their experiences via a pop-up survey designed in collaboration with Open Book Publishers under the Mapping the Free Ebook Supply Chain project, funded in 2016 by the Mellon Foundation. To avoid alienating users, the optional Free Ebook Survey prompt quickly disappears. However, a small proportion of users share their experiences, and some also offer to speak further, providing their email addresses.

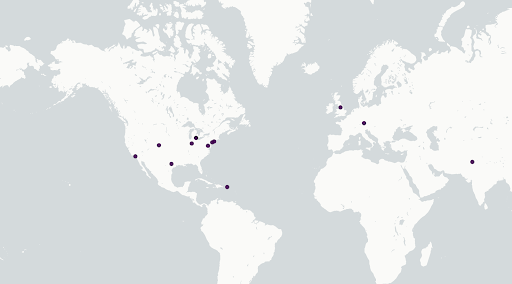

I contacted the 188 individuals who had opted in to be contacted for each collection, following up with a second email to ensure that my sample was geographically diverse. Of the 171 Lever Press respondents I contacted, 8 agreed to be interviewed. Of the 17 BTOB respondents, 5 agreed to be interviewed. The Lever Press respondents are currently located in 5 US states and territories, and 3 countries. The BTOB respondents are currently located in 5 US States (see Figure 2).

Figure 2: A map showing where the interviewees came from in the world. Generated using kepler.gl.

I then proceeded with semi-structured interviews via Zoom over the course of a month. Participants were asked three questions (“How do you generally find and access books?” “What interests lead you to this particular book?” and “Why is it important to you that the book was OA?”)from the study protocol, though one question was altered depending on whether or not they had read the book themselves. While the interviews were guided by the questions, I left room for wider participant discussion based on what they wanted to share about their OA experiences.

Each meeting was recorded, and the recordings were used to produce a typed transcript. I then anonymized and formatted these transcripts for upload into NVivo 14, a qualitative and mixed-method research software. After a valuable consultation with Michael Beckstrand (research project specialist, University of Minnesota), I undertook three rounds of coding:

- The first round of coding was coupled with the formatting work, which involved inserting headers to indicate which sections of text related to which questions from the study protocol.

- The second round of coding was a more inclusive version of the first. Each section was reviewed to see if it contained information relevant to more than one question.

- The third round of coding focused on the text gathered under the question codes generated in the earlier rounds. With responses coded under each question, I reviewed this text for key themes, focusing on individual participant responses and connections between participant responses.

I added a fourth and final round of coding, which was separate from the earlier rounds. Here, I returned to each transcript individually. Rather than focus on grouping by question, I reviewed the text to see what key themes and repeated words were present. The goal of this round of coding was to capture what participants said in response to being asked about OA in their own words. These keywords were technically not used to create codes but were recorded using the memo function and included as part of the analysis. I began the formal analysis stage by reviewing participant demographics and seeing what connections there were. I then considered these connections in conjunction with the codes and participant keywords.

The Findings

The goal of the analysis was not so much to provide an answer to a single hypothesis as to reflect on the data collected and detect themes in the reader experience broadly. While the two studies were conducted separately, three common themes, listed below, emerged. To stay true to the conditions under which IRB exemption was obtained, all participants’ names have been altered to random names (generated by https://www.behindthename.com/random/).

OA books can be recommended and shared

When asked how they find and access books, many interviewees noted that they either actively sought or received a recommendation for titles from another person or online source. I have divided these into personal/personalized/primary recommenders and secondary/general recommenders. The first includes book clubs, colleagues, and friends, while the latter includes online book reviews, podcasts, blogs, and email listservs. Often participants had more than one way to receive recommendations, and it usually was a mix of primary and secondary recommenders. This also tracks with data collected through the Free Ebook Survey tool for the BTOB collection: 30% of survey respondents said they found the book through Tumblr, a blogging and social networking website and app, and another 6% had another person recommend the book and collection to them.

“The best books, the ones that catch my attention, are the books that people recommend to me . . . I guess I read a lot of book reviews, and I listen to a podcast that is very book-focused called the Mars Hill Audio Journal.” - Devyn

“Well, it really depends…If I am generally not sure, I will go into the purchasing interface that my library uses…I also hear about books from other people or from blogs or websites or Listservs that I will then look into as well. And I mean, I will occasionally browse for books based on general subject area. So it's really a variety of ways, I would say.” - Kelsey

OA books can be reused, not just read

During the course of the interviews, it became apparent that since I initially focused on the participants as “readers,” I had not fully appreciated the variety of ways people could reuse OA books beyond just reading them. Sharing does not necessarily involve reading. Three participants accessed a book in order to share it with someone else without reading it (three others both read and then shared the book). Sharing behaviors included personal recommendations to friends and a librarian expanding their online offerings. If licensed appropriately, OA books are also easy to reuse creatively. One interviewee was part of an amateur bookbinding group that reformat relevant OA books to create and share unique physical objects. Another participant used a book as part of the generative process for an art project.

“. . . When I saw this on the list I immediately thought of Annette and sent it to them and they were indeed very happy to have it. They haven't sent me specific comments, but it did lead to our having a lovely lunch together again after not seeing each other for a long time.” - Aýna speaking about Leaders of the Pack

“I really have found it generative for the way that the author responds to the vulture [and] the vulture's behavior as a model for grieving . . . It's helped me feel like this is something worth pursuing, that other people have also seen the potential for the bearded vulture as a cultural model.” - Ivar speaking about Honorable Bandit

“Open access” means different things to different people

One of the major takeaways from the interviews was the various ways people understand and use the words “access” and “accessibility.” Interviewees interpreted these books as “being accessible” in a variety of ways:

- there is more availability and wider reception for niche topics;

- the availability of an English version means the work can be more easily shared across language barriers;

- digital copies are more accessible to people with disabilities (including being less risky to handle than printed copies);

- not having to navigate authentication mechanisms makes OA titles more accessible under time pressure, allowing the assignment of excerpts to students when preparing for courses;

- digital copies are more mobile than physical books, which is a great resource for people without permanent teaching or research positions;

- and when expert knowledge is easily available to be read, scholarship thrives and is more diverse.

Most of these benefits revolve in part around the digital format, but the value of it being free is implicit. The variety of benefits and types of accessibility mentioned here highlight the value of OA to readers.

“Well, first of all is the cost. Adjuncts don't get paid well, and every dollar we can save is helpful, and especially when you're talking about the prices of some publishers. One of my friends asked a couple of weeks ago if I knew about a certain book, and I said, ‘Yes, and given who the publisher is, I imagine neither one of us can afford it.’” - Leon

“The things that are useful to me about the open access program include first, mobility. I don't own the computer I'm talking to you on, it's owned by my university . . . . Digital manuscripts become part of the toolkit that the itinerant globalized scholar must carry. So now I can have his book wherever I am in the world when I have a need to cite something about the racialization of engineering institutions.” - Mila

“But also, I think that when it comes to particularly things in the queer book collection, in order to be accessible to queer people who are often economically more disadvantaged for a variety of reasons, it's great when they're free. And having access to that information, having access to stories that they relate to, having access to things that make them feel less alone in the world, it's important.” - Quinn

Conclusion

The number of interviewees in this study was small, and there was selection bias. For example, interviewees able to easily spend 30 minutes online within the interview window (7 am to 8 pm Eastern US time on weekdays) were more likely to respond. However, even a small study revealed an amazing diversity of human experiences behind the download numbers, showing that there is no such thing as “the average reader.”

Within the diversity, actionable themes emerged to inform platform improvements (e.g., “make sharing and recommending titles easy”) and ways of articulating the value of OA book publishing (“accessibility” is a resonant term with multiple meanings). As a result of this research, the Fulcrum platform is highlighting the sharing functionality in its ebook reader (allowing easy sharing of a full-text link on Twitter/X, Facebook, Tumblr, Reddit, and Mendeley), and the publicity generated for Lever Press and BTOB will encourage sharing and discussion of OA books in its publicity. Recognizing that accessibility means different things to different audiences. The teams will also be experimenting with new ways of describing the affordances of open access in their messaging.