My name is Qihao Liang, and I’m a rising senior in Sociology in the Honors Program. I am deeply grateful for the U-M Library Student Mini Grant, which supported my May 8 to 23, 2025 fieldwork in Taiwan for my honors thesis on investment and education migration between Mainland China and Taiwan since 2008. I also want to thank Dr. Liangyu Fu, Director of the Asia Library, whose research guidance, fieldwork planning, and safety check-ins made this work possible. Writing in mid-August, I see how being on the ground in Taiwan reshaped my project; embodiment became tangible (what Ruth Behar calls “the vulnerable observer”), bringing emotional resonance and my own researcher subjectivity into view. Stepping onto the island as a citizen of the People’s Republic of China (PRC) with relatives separated across the Strait, I learned that self-exposure, the experience of being scrutinized and scrutinizing, and the slow time of fieldwork with participants—walking, eating, talking, getting lost—led me and, I hope, my readers to places that Zoom calls, archives, and scraping Instagram, Xiaohongshu, or Threads cannot reach.

Night train on Taiwan’s Pacific coast, shot on a Polaroid as I headed back toward Taipei on the third-to-last day of fieldwork.

Project overview

“The most familiar strangers.” That was how a Mainland Chinese student described studying in Taiwan (Chao & Yen, 2018, p. 73). My interlocutors echo this tension: we speak nearly the same Mandarin, draw on a shared repertoire of “Chinese” culture and kinship, yet the air cools the moment identity or nationality enters the room. Across semesters and visa renewals, bewilderment often hardens into guarded indifference. This simultaneity, intimacy and estrangement at once, marks a distinctive form of co-ethnic migration between divided homelands, China (People’s Republic of China, PRC) and Taiwan. It unsettles nation-bounded ways of thinking about cross-border movement. From Cold War Germany to the Koreas and Sudan, divided polities pose a similar puzzle: how do governments of “the same people” manage the friction between shared heritage and sovereign difference as they claim, contest, and interpret jurisdiction over co-ethnic migrants?

Many states extend a familial hand to their diasporas, easing family reunification (for example, Hungary) or granting extraterritorial voting rights (for example, the Dominican diaspora). What Walzer (1984) called a “kinship principle” later developed into “kin-state politics” (Waterbury, 2011). During the Cold War, both the PRC and Taiwan worked within this logic, courting overseas Chinese for investment and knowledge transfer (Gao, 2003; Han, 2019). Since 2008, however, their paths have diverged. With direct flights restored after six decades, mobility quickened. The PRC expanded incentives and access to social benefits for Taiwanese migrants, while Taiwan adopted tighter immigration pathways and narrower welfare eligibility for Mainland Chinese migrants. The divergence complicates the assumption that shared ethnicity naturally produces inclusionary policy, showing how interstate competition can refashion kinship politics, turning a tool of transnational inclusion into an instrument of sovereign differentiation.

My questions follow from there. Why do two culturally proximate polities adopt opposing approaches to each other’s co-ethnic migrants? How do these approaches, together with ongoing political division, shape everyday life on the move? Focusing on migration between Mainland China and Taiwan since 2008, I ask how fragmented states govern across borders and how migrants’ practices, in turn, reconfigure those state projects.

I paired policy analysis from 1987 to 2024 with on-site fieldwork in May 2025. The dataset includes fifty in-depth interviews across two groups: Mainland Chinese students in Taiwan and Taiwanese businesspeople in the PRC, including adult children where relevant. On the policy side, I compiled regulations and administrative measures from both governments and tracked revisions over time. I read policy language to see how rules define who counts and what rights follow. I read interviews closely to understand how people experience those rules in daily life. The Asia Library shaped each step. With Dr. Liangyu Fu and colleagues, I refined bilingual keywords, identified PRC and Taiwan policy repositories, and planned archive visits and reading rooms; I also consulted UDNdata, Airiti, and the Taiwan Yearbook. The Student Mini Grant covered travel, local transport, printing, and the slow time needed to walk with participants, talk, and follow leads in person. All names are pseudonyms and identifying details are adjusted to protect privacy.

Four fieldnotes

- Whose language, whose accent

On my first day in Taipei, I realized I had not printed enough consent forms. Recruitment had grown from ten participants to fifteen. I was not worried. In Taiwan, convenience stores function as small infrastructures: electronics and hot meals, parcel drop-offs, lottery slips, even ATMs that recognize foreign cards, and, crucially, self-service printers. I asked the front desk at the fandian (飯店; hotel; Taiwan usage prefers fandian over the PRC’s jiudian 酒店 or binguan 宾馆) for the nearest 7-Eleven. In Taiwan, most people say it in English, “Seven-Eleven.” On the Mainland, people often say “qi yao yao” (七一一; using yao as the radio code for “one”). The difference is tiny. It is also audible.

It was a five-minute walk in 35°C humidity. Under the fluorescent hum, I went straight to the counter: “Ni hao, qingwen keyi dayin dongxi ma?” (你好,请问可以打印东西吗; hello, may I print something?) “Wo you ge dongxi yao fuyin.” (我有个东西要复印; I have a document to photocopy.) I softened my er sounds, leaning toward Taiwan’s Guoyu (国语; Mandarin as used in Taiwan), the voice that in the United States sometimes passes as Taiwanese. The cashier hesitated. “Dayin… sir, do you mean…?” I tried again: “to get a document printed.” His face cleared. “Oh, you mean lieyin wenjian.” (列印文件; to print a file.) A trivial exchange, yet there it was: how PRC Putonghua (普通话; Mainland standard Mandarin) and Taiwan’s Guoyu sort vocabulary into different drawers. On the PRC side, dayin 打印 for “print” and fuyin 复印 for “photocopy.” In Taiwan, lieyin 列印 is common for “print,” and many clerks will say yingyin 影印 for “photocopy.” Even at a 7-Eleven, language policy made me visible.

The differences multiplied in small ways. In the jichengche (计程车; metered taxi; Taiwan usage), a driver asked if I was Japanese or perhaps Malaysian Chinese. He had noticed my name on the booking. PRC agencies list my English name as “Qihao.” In Taiwan the same characters are routinely romanized “Chi-Hao,” so my Uber showed “Qihao,” unfamiliar to many Taiwanese; people often hesitate, unsure how to pronounce it or whether it is Chinese at all. Later, at a yakitori place, the masked cashier tilted his head. “You are not Taiwanese, are you?” “No, I am from the PRC, studying in the United States.” I could not read his expression beneath the mask. “Visiting?” “Yes.” “Alone?” “Yes, having a good time.”

None of this was dramatic. That is the point. Borders did not announce themselves in checkpoints or speeches. They arrived in cash-register pauses, in the choice between dayin and lieyin, in whether a hyphen sits between Chi and Hao. The everyday acoustics of a divided homeland, naming a store, hailing a cab, paying a bill, kept nudging me into view. In those nudges, the project’s questions returned with a smaller, sharper edge: whose language counts, and who gets counted, when kinship and sovereignty both claim the same tongue?

Local TRA train from Taichung HSR to the city center, roughly every fifteen minutes. Trains and HSR were my main way to move between cities to meet interlocutors.

- At the Counter, At the Border

I went to the National Central Library in Taipei to look up materials on Mainland Chinese students in Taiwan. At the registration counter for a reader card, a masked woman, medium build with bright eyes, her voice almost gone, was still on shift. She asked for my passport and my Rutai zheng (入台证; Taiwan Entry Permit for PRC nationals). I had already registered online using my passport, so being asked for the Entry Permit felt faintly awkward.

Next to me stood a white man about my height. From the soft bonjour-ish vowels in his Mandarin and a furtive glance at his passport cover, I gathered he was French, a PhD student. I considered offering to interpret, but he did not need it. His Guoyu (国语; Mandarin as used in Taiwan) was smooth, only punctuated by the occasional “ok, yes.”

When my clerk finished and began explaining the rules, she hesitated over a label. “You count as a waijisheng (外籍生; international student) … oh, waiji renshi (外籍人士; a foreign national).” I smiled and nodded, sensing she was choosing words to be kind. The moment was oddly dislocating. Legally, I stood with the French student under the same sign: waiguoren (外国人; foreigners), blue or red passport covers rather than Taiwan’s deep green. And yes, I study in the United States; I did arrive here from outside. But my “foreigner” status carried another layer, made contentious by history, language, and kinship, that made it hard to set myself alongside him without an asterisk. How should I introduce myself? Zhongguo ren (中国人; Chinese)? Dalu ren (大陆人; Mainlander)? Something else? Should I ask Taiwanese staff to mirror the term I use, or is it enough that each of us names from where we stand?

She told me I would need to register again “next time.” I asked, half testing the boundary, “What if I come back tomorrow?” She clarified that because my stay, as shown on the Rutai zheng, was only fifteen days, the “next time” meant the next entry. I nodded, “the next arrival,” and she nodded back. Then she slid over a slip the size of a sticky note with my account information: a username built from my PRC passport number, prefixed, she carefully pointed out, by a tiny dot, and a temporary password.

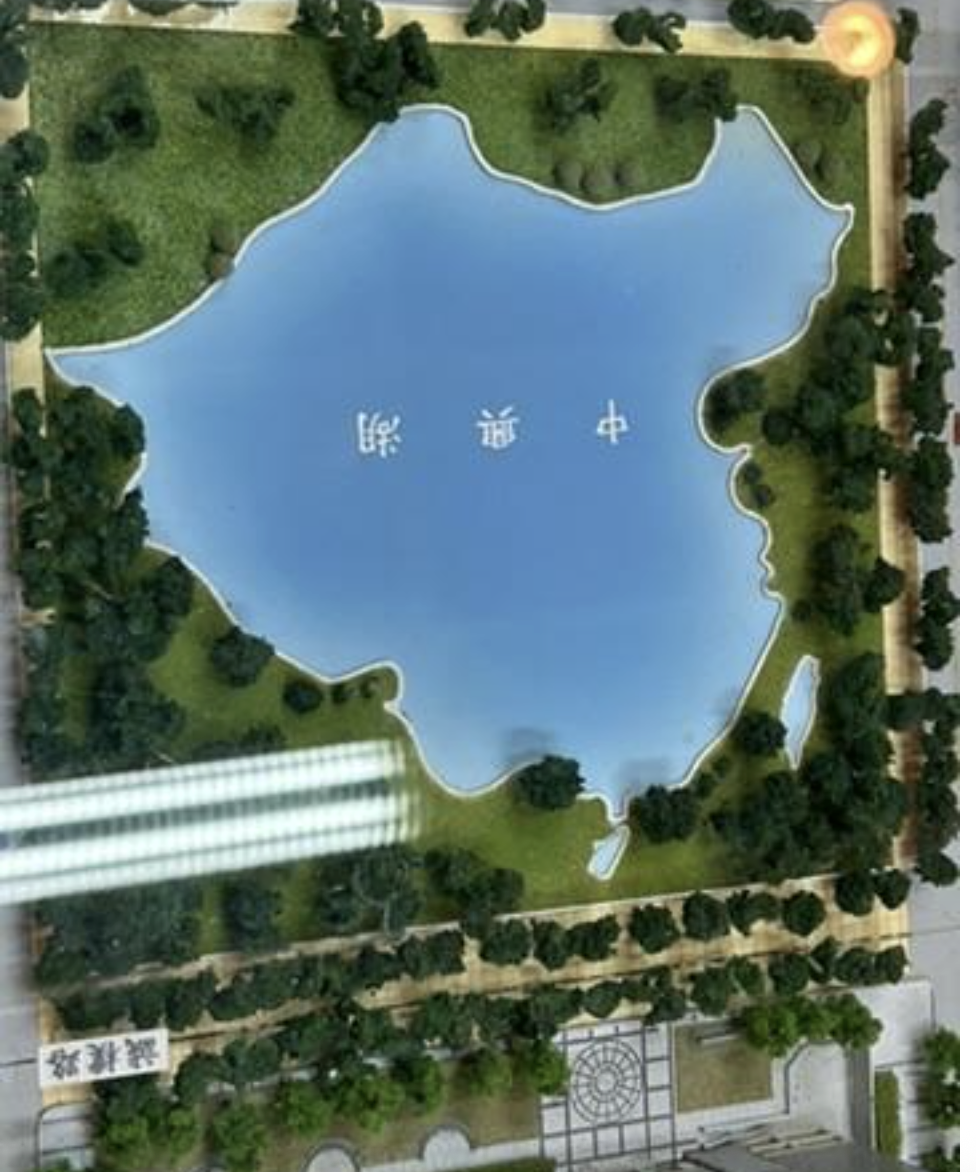

Campus history gallery at National Chung Hsing University displaying a model of “Zhongxing Lake,” shaped like a map of China that includes Taiwan. Staff explained that Zhongxing (中興) evokes “revival,” a name chosen by political elites of the Kuomintang who, after losing the Chinese Civil War and retreating to Taiwan, still envisioned counterattacking the Mainland to complete a national revival.

- Classroom

I followed one participant, Jin, to her media studies seminar. The professor, U.S.-trained and early-career, opened with a joke as I introduced myself: “Why would a xueba (学霸; overachiever) from America interview a xuezha (学渣; underperformer) like my student Jin?” I felt a flush of embarrassment at how quickly he reached for reductive, instrumental labels to sort me from my participant. Does studying in the United States automatically rank above studying in Taiwan? I was briefly at a loss for words. He went on, teasing: “So you came to Taiwan to have fun.” “I’m here to do research,” I said. “Impressive, topics even Mainland Chinese students in Taiwan do not touch,” he added, then asked what I had been hearing in interviews.

I said many Mainland Chinese students told me that once they realize marriage is, for practical purposes, the only viable route to remain in Taiwan long term, they begin to re-evaluate love, family, and reproduction, not only as private choices but as migration strategies. He pointed toward my participant and said, “she, too.” I startled at how easily a student’s intimate life could be folded into classroom illustration. He wore brown dress slacks and a blue button-down tucked in; the room also held two other Mainland Chinese students, juniors to Jin ( xuedi/xuemei 学弟/学妹; younger male/female classmates). They all seemed close.

The day’s first problem was a classic framing exercise (Tversky and Kahneman’s “Asian disease” in new clothing): two hypothetical drugs for 600 patients. Drug A will save 400 for certain. Drug B has a 2/3 chance of saving everyone and a 1/3 chance of saving no one. I was called last. “Four hundred deaths versus six hundred deaths both feel catastrophic,” I began. He cut in, surprised: “There is a big difference between four hundred and six hundred.” I heard the correction in his voice and could not tell if it was simply his style, or if, in that moment, he had filed me into a Cold War silhouette, the student from the “communist world” lacking a humanitarian instinct. I tried to clarify: “From an official’s perspective, if four hundred die, they are out anyway, so they might roll the dice.” He seized the phrase. “So, a gamble.”

Later, a student argued that capitalism excels at the “mere exposure effect,” saturating attention until preference follows. The professor smiled. “And other -isms do not?” He glanced my way, not quite calling on me, “Doesn’t communism?” It was not hostile; it was the kind of classroom microaggression that travels as banter, assigning each of us a role to play: the liberal skeptic, the critical theorist, the Mainland Chinese student as proxy for a system.

Footpath linking Yang Ming Chiao Tung University and National Tsing Hua University in Hsinchu. The sign toward Chiao Tung reads “Chiao-Tsing,” the sign toward Tsing Hua flips to “Tsing-Chiao.” A participant joked it is “one road with respective expressions (一路各表),” a campus play on the Kuomintang phrase “one China with respective interpretations (一中各表).”

- Love, marriage, family

In a juancun (眷村; former military dependents’ village) beef-noodle shop near campus, a Mainland Chinese PhD student, Po, lifted her chopsticks and said, “Sometimes living in Taipei feels like a dream, and dreams have to end.” Po wants to stay. Immigration rules make marriage look like the only workable route. She also knows the history. Mainland women who arrived as the wives of demobilized veterans, today often called lupei (陸配; Mainland spouses of Taiwanese citizens), were long positioned at the margins by law and by culture. “I’m an only child,” she said. “My parents love me. When they pass, I’ll inherit an apartment in China. Why should I make myself small just for a Taiwan ID?”

Her words called back an exchange in a conference hallway with a senior Korean scholar. Seeing me as LGBTQ, he said, “I’m LGBTQ too,” then offered pragmatic counsel about the United States: if you want to stay, do not do a PhD; while you are still young and charming, marry and get a green card. I was stunned at the time. Versions of that calculus surfaced again in interviews. Love, status, and family were rearranged as strategy.

After my first trip to Taiwan, I told my family in Zhoushan (舟山, an island city off China’s coast) about interviewing Mainland Chinese students there. My father joked, “You know you have relatives in Taiwan.” I was taken aback. I had never believed such a sentence would apply to us. Then came the story. In 1952, as the Nationalists withdrew from our coastal islands, their last footholds on the Mainland, local men were conscripted onto ships bound for Taiwan. One of them was my great-granduncle. In the early PRC, “relatives in Taiwan” was a politically dangerous fact, best left unspoken. Many families in Zhoushan carried similar histories, yet across generations children like me simply did not know.

Poster at National Chengchi University recruiting xueban (學伴; study buddies) for short-term Mainland exchange students, semester 114.1 in the ROC calendar. Taiwanese study buddies are often the first local friends Mainland students make; some are also roommates.

Acknowledgments

I am grateful to the U-M Library Student Mini Grant, the Asia Library, and Dr. Liangyu Fu. My deepest thanks to the Mainland Chinese students and Taiwanese businesspeople who trusted me with their stories. I am especially indebted to Professor Jaeeun Kim for her steady mentorship, and to the units that also supported this project: the LSA Honors Program, the LSA Department of Sociology, and the University of Michigan International Institute. As noted above, all names and identifying details are changed to protect privacy.

References

Chao, R.-F., & Yen, J.-R. (2018). The Most Familiar Stranger: The Acculturation Of Mainland Chinese Students Studying In Taiwan. Contemporary Issues in Education Research (Littleton, Colo.), 11(2), 73–82. https://doi.org/10.19030/cier.v11i2.10150

Gao, T. (2003). Ethnic Chinese networks and international investment: Evidence from inward FDI in China. Journal of Asian Economics, 14(4), 611–629. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1049-0078(03)00098-8

Han, E. (2019). Bifurcated homeland and diaspora politics in China and Taiwan towards the Overseas Chinese in Southeast Asia. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 45(4), 577–594. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2017.1409172

Waterbury, M. (2011). Between State and Nation: Diaspora Politics and Kin-state Nationalism in Hungary (2010th edition). Palgrave Macmillan.