The Project

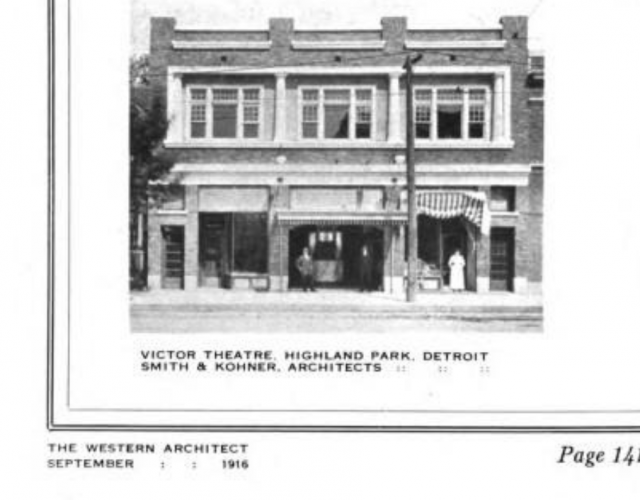

According to The Western Architect, four hundred and fifty million bricks were used in construction in Detroit in 1916. Among the brick buildings featured in this reporting is the Victor Theatre, located near the Ford factory that was, at the time, the largest manufacturing site in the world in Highland Park, an autonomous city in the center of Detroit.

Today, this building is the main location of the Ruth Ellis Center, a nonprofit organization providing social and medical services to LGBTQ youth in metropolitan Detroit. While the exterior of the building is now unrecognizable – the façade covered over in the intervening years – certain interior spaces in the theater have been preserved: the detailed proscenium arch framing the stage-turned-conference-room and the upstairs dance hall where, prior to the novel coronavirus pandemic and enforced social distancing, youth gathered to share meals and vogue during the Center’s drop-in hours.

As a PhD student in the joint program in Social Work & Anthropology, I began ethnographic research at the Ruth Ellis Center for my dissertation this past fall. Prior to that, I spent two years working with and for the Center – first, as a volunteer in the youth drop-in program and then as a part-time Data Manager for the Center’s Education & Evaluation team. Throughout this time, I became fascinated by the multiple intersecting histories still present in the physical space and social practices of the Center. The organization’s namesake, Ruth Ellis, is herself a key figure in the LGBTQ history of Detroit. A Black lesbian community leader and business owner, Ruth Ellis ran a printing press in Detroit and offered housing, support, and care to lesbian and gay youth in the city from the 1930s to the 1970s. When Ellis died in 2000, she was 101 years old and had lived just long enough to cut the ribbon at the grand opening of Ruth Ellis Center’s first site, before it moved to its current location. Today, Ellis’s portrait is displayed in almost every space – physical and virtual – that the agency occupies, and her legacy is regularly invoked by youth and staff.

When the Center made plans to renovate its current building, they also discovered relics of the building’s history hidden in the walls. Plastered over, a fragment of a poster from the Croatian Singing Society “Nightingale” Easter Concert of 1939 left one clue to the building’s past. Years later, when Carl Levin visited the center, a legend began to circulate among staff that he had recognized the space from his days as a young auto worker. As the story goes, he pulled out his wallet and revealed a tattered union card with the address, 77 Victor Street, listed as the auto union’s headquarters.

a fragment of a poster from the Croatian Singing Society “Nightingale” Easter Concert of 1939

As I began to develop my dissertation project at the Center, I became interested in following these trails about the social and material history of Highland Park and Detroit, and the ways these various histories intersected to make the Ruth Ellis Center possible. I also began to work closely with a group of young people who served as the Youth Advisory Board for the Center. When I shared what I had begun to learn about the history of the building through initial searches of online newspaper archives, they became interested in collaborating with me to document this history. Through a Rackham Public Scholarship Grant and the Library Mini-Grant, we were able to make this work possible, developing a collaborative archival and oral history project documenting the social and material histories of Highland Park and the Ruth Ellis Center.

Collaborative Archival Research

Following a community-based participatory research model, the design of this project was directed and informed by youth and staff at the Ruth Ellis Center and focused on the production of an interactive, multimedia history of the Center and the communities in which it is embedded. The Library Mini-Grant enabled me to support and coordinate this youth-driven research project and to compensate my collaborators on the Youth Advisory Board. I was also able to organize trainings for youth on topics relevant to our research, including a workshop on ethnographic filmmaking with Professor Damani Partridge and a talk about the architectural history of queer space in Detroit.

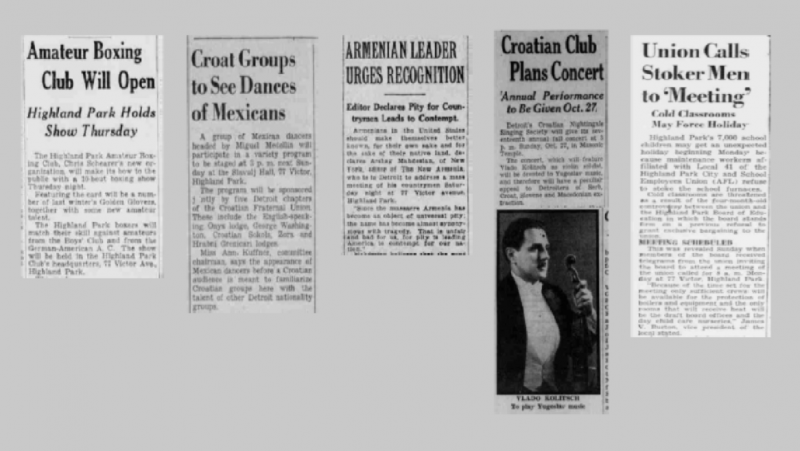

Our first step in this project was to collect every relevant document we could find about the Victor Theater. Through primarily the digitized records of the Detroit Free Press, we were able to uncover stories of its use throughout the last century as an immigrant club house and community center in the 1920s and 1930s, as the headquarters of an amateur boxing league, and as a site of labor union organizing in the 1930s and 1940s.

Excerpts from the Detroit Free Press, 1933-1944

Many of the earliest records of 77 Victor in the Detroit Free Press describe its use as the headquarters of the Highland Park Amateur Boxing Club. Publishing three stories its opening week, the Detroit Free Press publicized its first “boxing show” on Thursday, October 26, 1933, when boys from the Highland Park Club, the German-American Athletic Club, and the Boys Club of Detroit competed in a Golden Gloves bout. Articles in the Detroit Free Press go on to cover several performances of the Croatian “Nightingale” Singing Society featured in the poster discovered inside the Ruth Ellis Center’s walls, including a performance at the Masonic Temple in 1940, with over 1,000 in attendance, and at the Detroit Institute of Art with a banquet following at 77 Victor. In 1938 the Croatian Society established a permanent residence for themselves, purchasing 77 Victor as their first clubhouse. Over the years, the Croatian Society lent its space for performances and gatherings of the Rumanian “Abraham Lincoln” Society and Czech groups. Collaborations like these seem to have been intended to foster cultural exchange, as in the case of a 1941 event in which the Croatian group invited a group of Mexican dancers to perform “to familiarize Croatian groups here with the talent of other Detroit nationality groups” (Detroit Free Press, Sunday, November 16, 1941). In 1942, the Society added a newsreel film screening and a dance to their annual festivities (Detroit Free Press, March 22, 1942).

In the same era that the building was used by the Croatian Society, 77 Victor became a hub of labor organizing activities. In 1938, a newly formed group with 800 members, the Building Tradesmen’s Union of America, held a mass meeting on a Wednesday evening in the building to form their organizational policies (Detroit Free Press, Friday April 22, 1938). On 1941, 400 members of the City Employees Union, Local 77, met there to vote on a strike. On May 3, 1942, the newly elected president of the Ford Highland Park Local of UAW was inducted at the local hall in 77 Victor, now listed as the headquarters of the union, with Joseph G. O’Connor, the International representative, presiding. In 1944, on the cover page of the Detroit Free Press, an article details a potential school closure due to the union organizing activities of the “stoker men” of Local 41, the Highland Park City and School Employees Union (AFL), who met to vote on a strike on Monday, March 27. The maintenance worker union called a bargaining meeting with the Board of Education that day at 77 Victor, creating the possibility that cold classrooms, unheated by the absent maintenance workers, might cause schools to close.

While the archives of the Detroit Free Press led us to a great deal of historical material, we also encountered archival road blocks. Highland Park, founded as an autonomous municipality surrounded by Detroit in a tax scheme by Henry Ford to protect the wealth of his factory, is now in many ways an extreme microcosm of Detroit. With the closing of the city’s factories, the city has experienced profound de-population, disinvestment, and the closing of its public institutions, including its once grand McGregor Public Library. The archives of Highland Park—undigitized and often inaccessible—tell their own story of the city. In searching for records of the building that has become the Ruth Ellis Center, my collaborators and I found ourselves poring over what newspapers we could find from Highland’s Park more affluent past in a public library in Detroit.

McGregor Public Library, Highland Park, 1918

This Library Mini-Grant also allowed us to better confront the challenges of this archive. First, my meetings with my library mentor, Julie Herrada, helped me to think more creatively about how to use the University’s library resources and how to access the archives of Highland Park, Hamtramck, and Detroit. We were also able to shift our focus to collecting and videotaping oral histories of community members and organizers intimately acquainted with the histories of Highland Park, LGBTQ organizing in Detroit, and Ruth Ellis.

Collecting Oral Histories

Throughout this project – until it was interrupted by our current crisis – my collaborators and I met regularly to interview and record meetings with Ruth Ellis Center staff and founders, community members, and local residents. We learned about the organization’s history, the history of Highland Park and the neighborhood surrounding the Victor Theater, stories of LGBTQ community organizing, and the life and legacy of Ruth Ellis.

Next Steps

In the next few months, my collaborators and I will be working to continue this project virtually while physically separated. Once we have completed our archival searches and oral history interviews, we will work to edit and compile our material into a film that will document this work and preserve this history for the Ruth Ellis Center to use and circulate. In preserving and curating these histories, my collaborators and I hope to center and elevate the voices and stories of those who have made the Ruth Ellis Center possible, as well as the young people served by the Ruth Ellis Center today.

Kathryn Berringer is a PhD Candidate

in the School of Social Work &

Anthropology at the University of Michigan