From mid-May to mid-July this summer, I joined the U-M Library’s International Studies team as their Southeast Asian studies librarianship intern. I applied to the inaugural internship program, hoping to build upon my previous work experiences in metadata and cataloging services at three different academic libraries in California and Massachusetts. As a student copy cataloger and a part-time assistant, I mainly proofread certain parts of bibliographic records that are considered crucial (e.g. book titles, page numbers, etc.) and transferred records from a shared online database to a local one used by the U-M Library. In other words, I did what is called copy cataloging and other entry-level tasks involved in processing new library materials. In short, I arrived in Ann Arbor with the goal of expanding my understanding of librarianship, which was limited to a few library jobs I have had.

During the first four weeks of the program, my fellow interns and I went through modules created on Canvas for the internship, both through self-study and in morning class meetings led by Beth Snyder, the head of International Studies Technical Services, and Leigh Billings, the metadata management librarian. We were introduced to the role of technical services in library administration, its workflows, and collection development tasks like selecting and ordering books as well as cataloging. Beyond classroom time, we went on tours to other libraries beyond the Hatcher Graduate Library and participated in staff meetings. At the end of each week, we had a discussion section for a chapter from Lesley Pitman’s Supporting Research in Area Studies. Our discussion was facilitated by Jeffrey Martin, the South Asian studies and Anthropology librarian, and Fe Susan Go, the librarian for Southeast Asia, Australia, New Zealand, and the Pacific Islands. What was distinctive about this is that the two librarians served as a corrective for the somewhat outdated book, which was published in 2015, with their knowledge of the current states of affairs in the field. We were also fortunate to have our internship coincide with the search for a librarian in Western European studies with Germanic focus. I relished the opportunity to attend the job talks because I got to see for myself what kinds of jobs really exist in librarianship and what job candidates are asked to do to demonstrate their fit for the position.

Given my specialization in Southeast Asian studies, I worked closely with Susan and the Southeast Asian Studies Specialist Sujira Meesanga Prayoonhong. Susan gave me first-hand glimpses of what it is like to work with publishers in Southeast Asia and to select newly published materials from vendor catalogs. I worked on four such catalogs - two on Burmese books, one on Indonesian, and one on Malaysian - and discussed my selections with Susan. One of my fondest memories during my eight-week stay in Ann Arbor is working with Sujira to do original cataloging (i.e. creating bibliographic records from scratch). This is especially important for materials in a less well-known language like my native tongue Burmese. If a record has not been created for a book or if the one created is severely deficient, it cannot be made available to researchers. Also, when it comes to Burmese, it is hard to find expertise in the language among library staff. So, Burmese books with problematic records or none at all remain in the backlog of the library for a long time, if not indefinitely. I learned during the internship that this is called the “hidden collection” problem. Towards the end of the internship, Sujira and I managed to rescue six of such problematic materials from the backlog limbo.

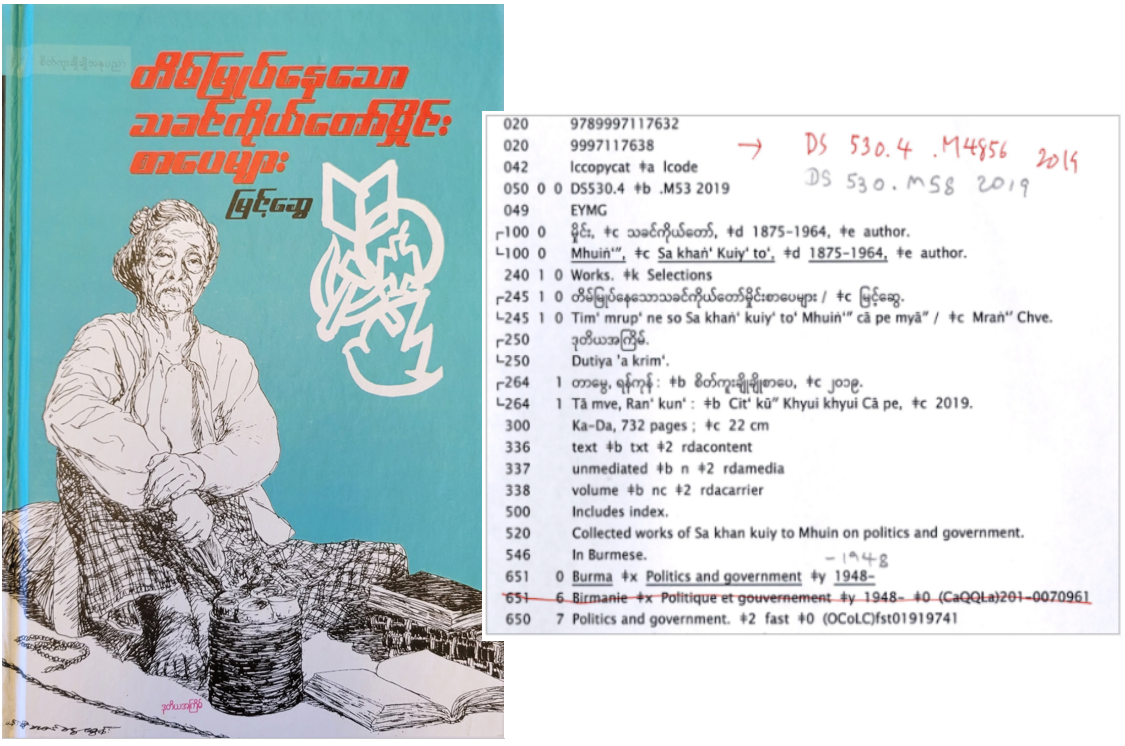

The front cover of a Burmese language book and the in-progress copy cataloging worksheet of the bibliographic cataloging description for the book.

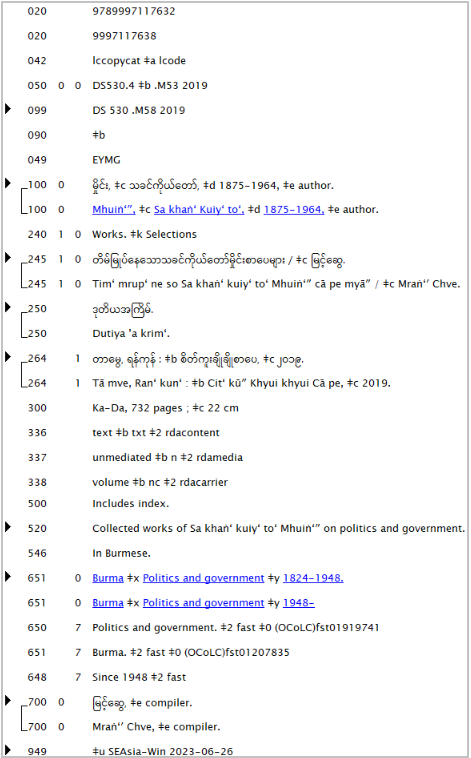

The completed bibliographic cataloging description of the book rendered in MARC format.

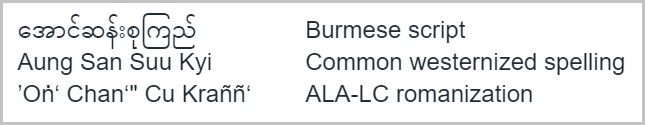

Another problem I addressed during the internship was the user-unfriendly transliteration system used by the Library of Congress to romanize Burmese. While the system is standardized not unlike the Chinese pinyin, it is based on how classical Indic languages like Pali and Sanskrit are romanized. This is partly understandable because the Burmese alphabet has been historically modeled on that of Pali and Sanskrit and it is used to systematically transliterate words from those Indic languages. The problem is that the transliteration looks foreign to native speakers as it does not reflect current pronunciation, not to mention the confusing diacritics. For example, the name of probably the most famous Burmese person “Aung San Suu Kyi” is romanized as “’Oṅʻ Chanʻʺ Cu Kraññʻ.” So, some basic knowledge of the Indic languages is unjustifiably assumed in a patron not only to decipher transliterated titles but also to look up titles one is looking for. The current solution for this problem is to include Burmese script alongside transliteration. While at U-M, I proofread such improved records and put in Burmese script for those that lack it.

Aung San Suu Kyi’s name written in Burmese script, common westernized spelling, and ALA-LC romanization.

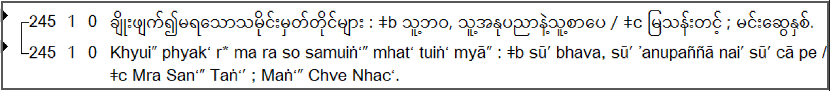

Example of paired Burmese and romanized script title and author fields added to a record.

In short, the inaugural internship program gave me a rare opportunity to meaningfully explore academic librarianship as a career through assigned readings, hands-on work, and interactions with the current staff. I benefited from the training sections given by metadata librarians, one-on-one and small-group discussions with area studies librarians, as well as close supervision of my own works by a relevant area studies specialist. I particularly appreciated the personal stories shared by the staff, whether they were about old technologies used by library staff or book-hunting adventures in Southeast Asia. I found this personal and historical touch valuable because it allows me to understand librarianship concretely, in time and space. It was also a pleasure to learn alongside my fellow interns -- the South Asian studies librarianship intern, two PhD students, and a master’s student from the School of Information. Each of them enriched my experience with their unique perspectives and ethical concerns about librarianship. Ultimately, I came out of the internship program with a more nuanced appreciation of librarianship and its intellectually dynamic nature. As someone whose research relies on primary and secondary sources in languages other than English, I am happy to have processed 155 Burmese books and made a contribution to the collection at the U-M library by the time I left Ann Arbor.