The Ladino language, which is also known as Judeo-Spanish and Judezmo, developed among Jews who were expelled from the Iberian Peninsula in the 15th and 16th centuries. Based on early modern Castilian Spanish, Ladino migrated with its speakers and gradually took on elements of co-territorial languages such as Ottoman Turkish, Greek, and Arabic, as well as European languages such as Italian and French.

In a controversial study, Tracy Harris (1994) proclaimed the death of Ladino. Harris discusses the historic trajectory of the language and the reasons for its so-called “decline” and “death” after the Second World War.

But is Ladino really dead?

Some evidence suggests that might not be the case. The recent rise in interest in and study of the language, especially since the Covid-19 pandemic, had been dubbed the “Ladino Zoom boom.”

Even before Covid, there has been a steady increase in resources devoted to the study of Ladino and its culture, most notably at the University of Washington, UCLA, and here at U-M.

This interest is also manifested in the increased visibility of the language in popular culture, with Netflix shows such as “The Beauty Queen of Jerusalem” and “The Club,” and English-language novels such as Elizabeth Graver’s Kantika.

Yet another potent example of Ladino’s cultural revival is illustrated in the recent reprinting of seven formerly unknown Ladino romance novels. The new publications come from Gozlem Gazetecilik Basın ve Yayin A.S., the only Jewish publisher in Turkey, founded in 1984. These works, which are held by the U-M Library, were originally published in Istanbul in the 1930s. There is almost no information about some of their authors, such as Moiz Habib, Eliya Gayus, and Albert Habib.

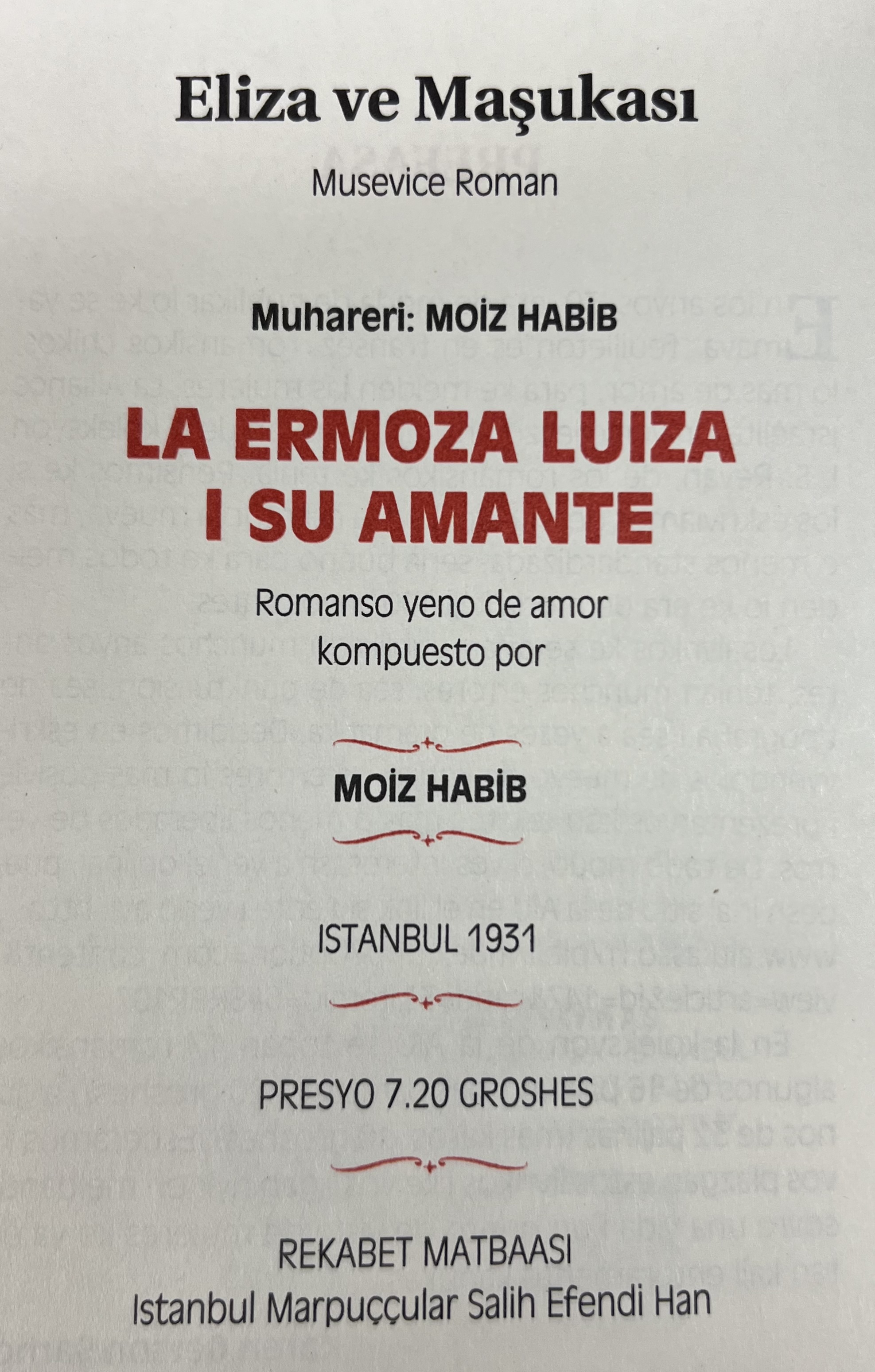

The title verso page of La ermoza Luiza i su amante, a novel published by Moiz Habib in Istanbul in 1931. It also includes the novel's title in Turkish, Eliza ve Maşukası. Below the Turkish title appears the designation "Musevice roman," which means "a Jewish novel" (using a term roughly equivalent to "mosaic").

The new editions of the romansos (as novels were called in Ladino) contain stories of love, intrigue, and crime. Unlike their original publication, these new editions are decorated with colorful images that recall movie posters from Hollywood’s golden age. The novels’ plots are set in diverse locations and periods: some in Western Europe - England, France, Spain - while others take place in locations as remote as New York, Buenos Aires, and Sydney, Australia. The majority of the characters are not identified as Jewish. What can we learn, then, from these literary works about Jewish life? How do they contribute to the preservation of their language and literature?

Firstly, the romansos provide us with a glimpse of the cultural lives of Sephardi Jews in the 1930s, and especially the perception of literature and its function in society. As was the case with many works of popular fiction, these texts contain educational content despite their foreign settings. For example, in El amor de Matilda Kon dos jovenes (Matilda’s Love for Two Young Men) which was originally published by Moiz Habib in 1931, the French heroine is depicted as “not having any thoughts about going to balls, theaters, and other vices.” Instead, “all her thoughts were dedicated to learning new things and spending her days studying, with her books.” Therefore, even though the plot is set in the fictional French town of “Shalom Sur Mer” (a conspicuously Jewish name), the author nonetheless uses it to present what was considered proper feminine behavior - and what was marked as improper - through the models of his fictional characters.

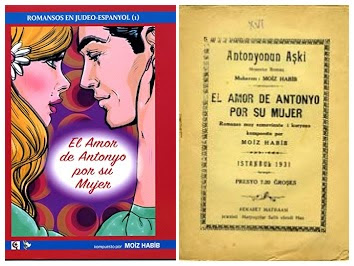

The novels also show the diverse strategies used by writers of popular fiction to intrigue and entice their readers. For many, this entailed crafting sensational plots and setting them in remote and exotic locations. A case in point is Moiz Habib's novel, El amor de Antonio por su mujer (Antonio's love for his wife), originally published in Istanbul in 1931. The following is a translation of the opening paragraphs:

In a small village in Morocco, a pale, skinny figure of a man passed through the streets, accompanied by two police agents, as the entire village shouted: Get him! He’s the one! He’s the infamous killer!

They circled him and looked at him with curiosity. Who was this man? That is precisely what we will tell our dear readers.

This man, whose name is Antonio, was unscrupulous and smart. He would catch horses, dogs, cats, wolves, and other animals in the mountains. Then he would bring them to the village, skin them, sell the meat here and sell the hide there. That is how Antonia sustained himself, with this dirty work.

This opening plunges Ladino readers into a remote an unfamiliar setting, away from the urban surroundings in Istanbul. It also piques their curiosity by placing a sensational trop - a murder - in the very first lines.

The covers of the original publication of Moiz Habib's novel, El amor de Antonyo for su mujer as it appeared in 1931, and the cover of the new edition from 2016.

Another instructive facet of the new editions comes in the form of information preserved from the original publications. Such are, for example, the final pages of Habib’s Sinko matados por una mujer (Five Murders by One Woman), where we can see additional content that appeared in the original publication. The first supplement is “Proverbos morales,” a list of Ladino refrains about ethical conduct. The second is “Kualo kale tener para ser ermoza” (how to be beautiful), which reveals the beauty ideals and behavior standards for Sephardi women:

Three white things: skin, hands, and teeth.

Three dark things: eyes, eyelashes, eyebrows.

Three pink things: lips, gums, fingernails.

Three long things: life, arms, hair.

Three short things: ears, teeth, tongue.

Three wide things: forehead, shoulders, intelligence.

Three narrow things: hips, mouth, pinky toe.

The effort to reprint these new Ladino editions is spearheaded by Karen Gerson Şarhon, the coordinator of Istanbul’s Sentro Sefardi. Şarhon is also the editor-in-chief of El Amaneser, the only Ladino-language publication in the world today, and of the Ladino page of Şalom, the Jewish weekly newspaper of Turkey. The new editions are based on texts collected and digitized by the Alliance Israelite Universelle in Paris.

Other works by Karen Gerson Şarhon held at the U-M Library include La Famiya Mozotros, the first and only book of caricatures in Ladino, containing drawings by Irvin Mandel and depicting the everyday life of the Jews of Turkey; and La izla preta, a Ladino translation of Hergé’s Adventures of Tintin. To read more about the state of Ladino in the 21st century, see this article by Tracy K. Harris (2011).

As of September 2023, the U-M Library holds over 400 items that include the Ladino language.

All the English translations are by Marina Mayorski.