Larry Wentzel, in collaboration with Randal Stegmeyer and Shannon Zachary

The Harry A Franck Collection consists of roughly 9,000 photographic originals — still image negatives (ranging from 3.25" x 4.25", 3.25" x 5.25", and 4” x 5”), 35mm and 45mm roll film negatives, sheet negatives, and hand-colored lantern slides. The focus of this post is not on what the content of the collection is — the Franck family’s travels through Asia, South America, and the US between 1910 and 1946 — albeit very interesting, but rather how the collection was digitized, and the lessons we learned along the way.

Spoiler alert: We did not learn that the answer was inside us all along.

Since it was donated to the Library, most of the Franck collection has been stored in freezers because of the type of film Franck used for his photographs: nitrate film. Nitrate film (nitrocellulose, or as it’s better known, “celluloid” film) was used from the late 1880s to the 1950s. Its most defining characteristic is that it’s chemically unstable — in poor storage conditions, nitrate film can deteriorate to the point of spontaneously combusting. Entire movie warehouses of old films have gone up in flames because the nitrate films were stored improperly there. The recommended method for long-term storage of nitrate film is to place it in a frost-free freezer and keep it there. Keeping the film consistently at freezing temperatures inhibits deterioration, minimizing the risk of spontaneous combustion. Sadly, it also prevents researchers from accessing the content and burdens the Library with maintaining and monitoring freezer storage indefinitely, particularly through power outages.

Digitization offers a way around these problems. Once the film has been brought back to room temperature, we digitize it at high resolution and save the image files on servers. The images can be made available online, providing researchers with all of the access they never had before. With the content digitally preserved, the Library can dispose of the original film negatives safely and reduce the cost of maintaining and monitoring freezer storage. Wins all around!

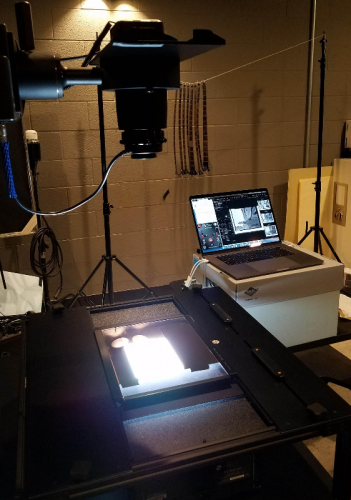

Setup:

Digital camera on a copystand with a lightbox.

Image credit: Larry Wentzel

Initially we considered using the film digitization equipment we already had — an Epson Expression 11000XL flatbed scanner with a transparency hood and slide trays. It’s certainly possible to digitize the film this way, but the time needed to complete the work is prohibitive — using a flatbed scanner to capture all 9,000ish negatives at high resolution would have taken 10 months minimum to complete. That’s a huge commitment for our photographer whose services are in high demand.

In the interest of time, we opted to upgrade our digital camera equipment, adding a lens extender tube, an improved electronic shutter, a preservation-grade lightbox, anti-newton ring glass, and metal frames to hold the film (all made possible thanks to special project funding from Bryan Skib and Maurice York, division heads for Collections and Library Information Technology, respectively). These upgrades reduced the project time to a more reasonable 4 months, including breaks for the photographer to work on other projects.

Equipment:

- 100 MP PhaseOne Q3 digital camera on copystand

- Lens extender tube for increased magnification

- Specialized lightbox, lens, glass plate, and film carriers

- Macintosh laptop

- Capture One Cultural Heritage software for image capture

- Adobe Bridge and Photoshop Creative Cloud 2019 for image processing

Process:

- Conservator pulls a box of film out of the freezer to thaw for 24 hours

- Once the film is thawed, the conservator — working in a fume hood — opens the sealed packaging used for storage

- Conservator updates the content spreadsheet with a list of film packages in the box

- Conservator hands the box of film over to photographer

- Photographer digitizes the film on the copystand

- Photographer updates the content spreadsheet with image filenames

- Photographer passes the film back to conservator for appropriate disposal

Challenges:

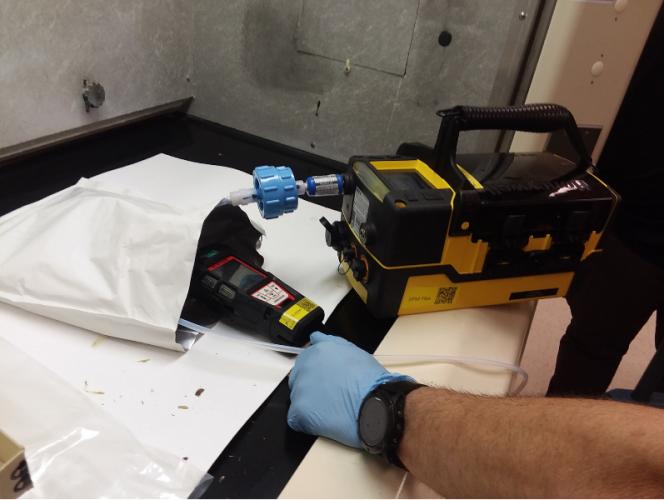

The conservation staff initially had concerns about the film off-gassing and creating a hazardous work environment. Conservation arranged for the U-M Department of Environment, Health, and Safety (EHS) to come and monitor off-gassing while the film was unboxed and being worked on in the Conservation and Digital Photography Labs. Surprisingly, EHS didn’t detect any off-gassing in either space, so the film posed no environmental risk to the employees.

EHS testing a film packages for off-gassing

Image credit: Randal Stegmeyer

On the recommendation of EHS, the Conservation Lab borrowed a portable water fire extinguisher for the duration of the project, which would be more effective than a chemical extinguisher, just in case a spark touched off the film.

Some of the film negative packages had suffered deterioration before they were put into cold storage. In some cases, the negatives were fused together along one or two edges which the conservator was able to separate. While some of the image area was lost, often the core of the picture was left intact. However, a few packs of negatives were so badly fused that the entire batch had to be thrown out undigitized. We also came across a handful of long film rolls folded to fit in envelopes while other rolled film was still in rolls. The film has to be encouraged to lay flat before it could be digitized without damaging the film in the process.

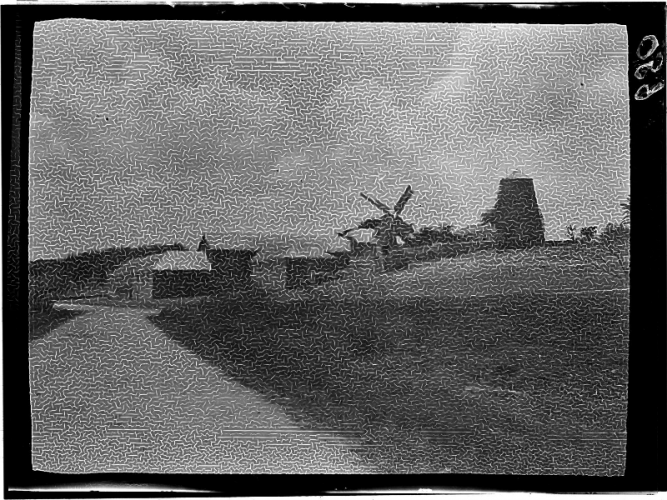

We discovered the original photographer made the same mistakes as anyone else when taking and processing their own film. Some images are out of focus; the film was under/overexposed; it was only processed partially and/or badly, in one case causing reticulation.

Example of a photographic negative suffering reticulation from the Harry A Franck collection.

Image credit: Randal Stegmeyer

The wide variety of image problems means that the digital photographer must process each image separately to adjust for the individual problems, rather than batch processing them uniformly.

Finally, we anticipate that some content was duplicated. Franck himself selected some images to become illustrations in the travel books he wrote, and some were converted into lantern slides for public lectures. He evidently used a commercial service to create the lantern slides, which included hand coloring each image. Some of the best images, therefore, probably exist in two versions: the original negative and the lantern slide.

The project plan does not include de-duplication of these images. To be perfectly fran(c)k, we have no idea which particular images in the collection were duplicated, nor how many. Also, we can’t predict which version will be of greater importance: one researcher may prefer the black and negative image, another researcher could favor the handcolored lantern slide, and others still would want both for comparison and contrast.

Completion?

Whatever timeline we had for finishing this project has been set aside due to the COVID-19 pandemic. All of the negatives and digitization equipment are stored in our facilities, waiting for us to return and pick up where we left off. Once we’re allowed to return to work, we’ll also be working at a slower pace — materials will be quarantined, shared equipment cleaned regularly, and social distance maintained between coworkers to prevent the spread of infection.

But stay tuned. Once the digitization project is done, we’ll let you know.