The University of Michigan Library’s Bible: King James Version (KJV) digital collection is one of our oldest and most-visited text collections and, based on web analytics, has a loyal following of returning visitors. At nearly 30 years old, the collection’s design reflects the early days of the Web with minimal identifying information. With effort underway to update the functional underpinnings of our digital collections, it was time to return to the KJV to study how well the text would work within our updated site layout, which is now used across the majority of our text collections.

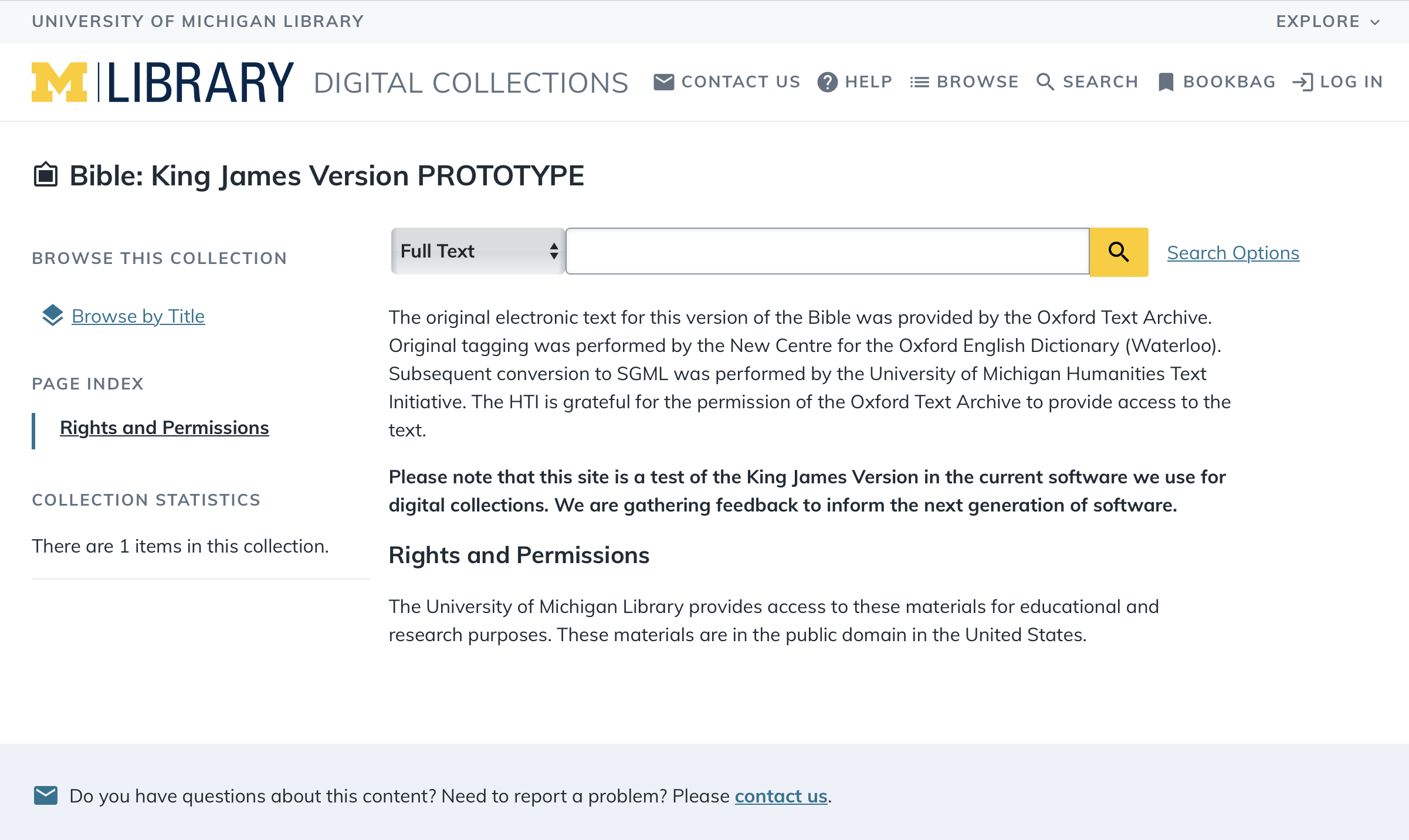

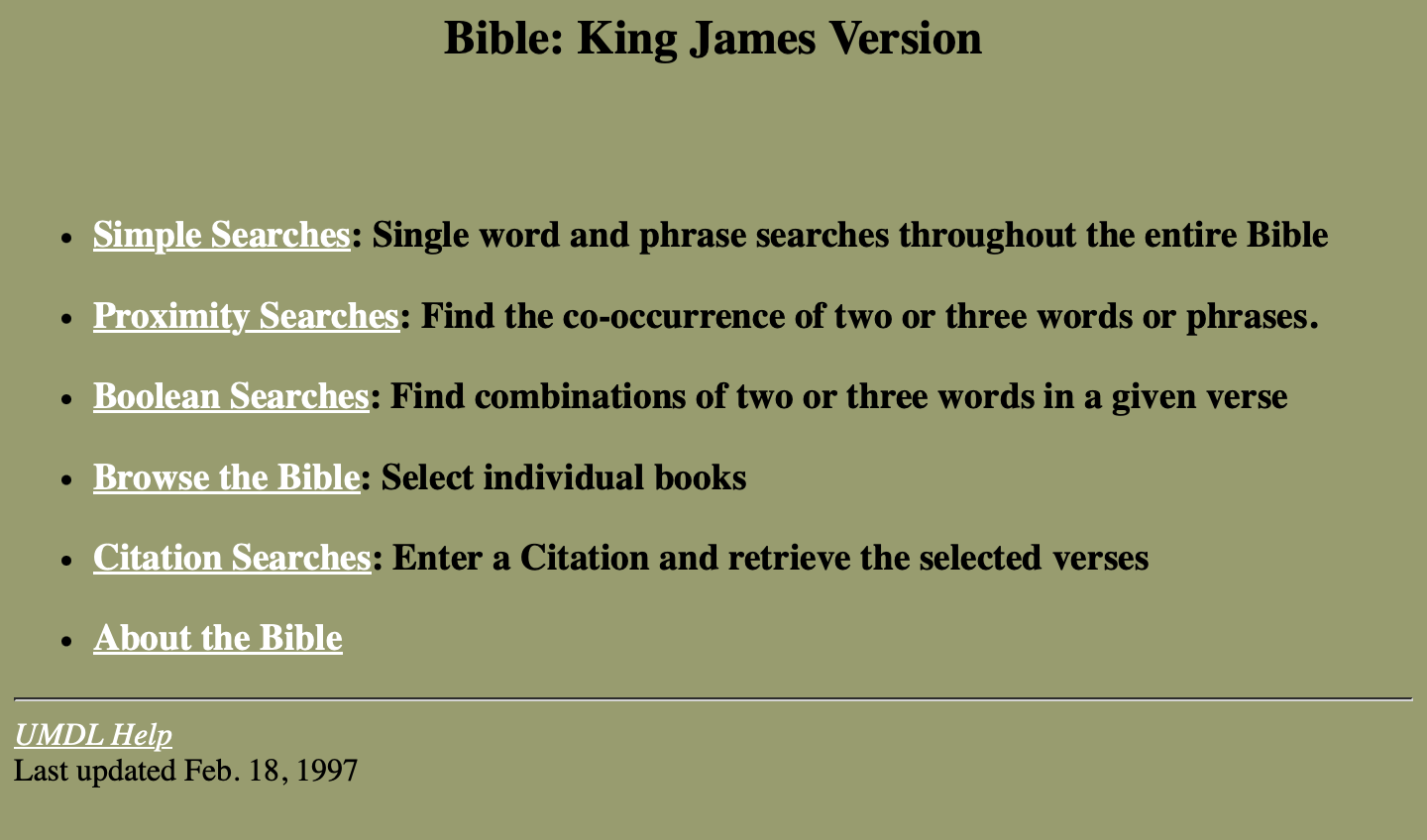

The difference between the current version and the preview is dramatic (see the two screenshots below for comparison).

The preview version of the King James Bible text collection

The current version of the text collection

Note, that the KJV isn’t the only religious text among our digital collections. We also host digital collections for the Atharvaveda (access limited to U-M), Book of Mormon, and the Koran and several other versions of the Bible: Bibel, Martin Luther Translation, Rheims Bible: The New Testament, and Bible: Revised Standard Version.

What makes the KJV digital collection special?

The KJV is a lengthy single-text collection with a few distinctive qualities beyond its age.

It is a text-only format without the corresponding physical page scans that are included in many of our other text collections. The structured markup of the content creates a nested structure – testaments, books, chapters, and verses – and longer passages, rather than the page-based presentation of our scanned volumes. This leads to a less than ideal presentation of the content, as the current platform was originally designed for the presentation of page-length content and page images. Also, due to this structured markup, verse numbers do not appear in the snippets shown for search results because structural parsing hasn’t been applied at this point. Instead, verses listed in search results are preceded with a “ / “ to show where they begin.

Beyond the uniqueness of these content qualities, the audience for this collection ranges from casual readers to members of the clergy to literary and biblical scholars. Many of whom, as previously mentioned, are loyal, longtime users who are very comfortable with the existing site.

How we tested

We began by posting an online survey on the existing version of the site to identify current users to recruit for a follow-up usability testing and received 250 responses. Nearly half of the respondents agreed to answer a longer version of the survey with greater detail about their experience on the site.

Key findings of the survey included:

- A majority of survey respondents visit the site regularly for personal use or to prepare for sermons or bible study, and they choose the site because it is simple and reliable.

- Features they like are no ads or commentary, easy to copy and paste, fast loading times, and robust search for exact keyword matching.

- Features they dislike include the limitation of our current search necessitating an exact match of terms and phrases and, for some users, inclusion of Apocrypha content (more on that later).

In follow up, we performed remote usability testing with 11 participants to observe interactions with the new version of the site. To prevent spending time on technical connection issues, we limited participation to those who had access to Zoom, but still were able to bring in participants from a range of backgrounds. The tasks focused on sharing overall impressions, trying search and browse functionality, and reading content pages.

What we learned

Although we had tested several other text collections with the updated digital collection design over the past few years, there was still room to learn about how people interact with our digital collections. Testing with the KJV demonstrated areas for improvement within the KJV site, specifically, as well as improvements that affect all our digital collections.

What we learned about the KJV

Critical findings specifically about the KJV include:

Lack of version information. Librarian and scholarly participants desired clear identification of which specific edition of the King James Bible is reflected in this text.

The King James Bible was first published in 1611. However, following that original printing, there were many subsequent printings through which errors were both corrected and added due to the cumbersome process of laying out movable type for each page. Our KJV version is most likely the Oxford edition published in 1769, which tidied up many typographical errors and lightly edited a few passages for clarity.

Related to questions about versions of the King James Bible, the 1769 Oxford version includes the books of the Apocrypha, from the Greek for "hidden away,” which are additional books of the Bible that are not part of the Old and New Testaments. In many modern editions for the King James Bible, these books are not included. Both in our user survey and in some testing sessions, participants were often surprised or frustrated to see the books of the Apocrypha in their results, as these books are unfamiliar to them. To enable users to tailor their searches, we added a search scope option for “Old and New Testaments” to exclude the Apocrypha in search results, in the preview version of the KJV.

Scrolling to locate highlighted keywords when viewing pages included in search results. When textual content is longer than a standard written page, such as full books of the Bible, locating search keywords was more challenging.

Almost all testers were surprised to go to a full Bible chapter and to not immediately see the text snippet shown in their selected search result. This may have been exacerbated by item information, such as stable linking and citation information, shown at the top of every page. When encouraged to scroll the page participants noticed the highlighted keywords and regained confidence in the search performance, but initially they exhibited confusion or hesitancy that links would take them to their results.

This finding highlights differences between using page-bound text collections, which have page scans and shorter content pages, and using un-pagebound text-only collections like the KJV, with an increased need for scrolling (and scrolling and scrolling). This finding suggests that features optimized for one kind of text collection may not work as well with others.

What we learned that applies to all

We also observed some universal concerns that affect all collections using the updated template. That we found new issues in already-tested designs highlights both why we test and why usability testing isn’t comprehensive. Different users, in this case passionate users with deep subject expertise, saw different qualities than previous participants. Additionally, different rounds of testing focus on different kinds of tasks or use a different content that illuminate different interpretations or experiences. Particularly in this study, with more non-academics and more long-time users, we saw a deeper exploration of content in context than when we have people explore a site or material they’ve never seen before. Additionally, we had one participant testing via mobile phone and another who used the JAWS screenreader, which uncovered previously missed issues.

Some insights about the system as a whole include:

Issues with cleanly copying-and-pasting keyword-highlighted text. While Bible verse content was displaying clearly onscreen, our participants found that copying-and-pasting carried along the markup used for labeling keyword highlighting, which required editing to produce a clean text snippet. This was a significant issue because users frequently come to the site to gather quotations to share with others or preserve in their research notes. Fortunately, the project team was able to quickly correct this shortcoming across all of our text collections.

Unclear instructions or features of search functions. Several participants had questions about how to use search functionality, including questions about the meaning of the on-screen instructions. Updating this text to be more helpful in context is on our list of things to do.

Confusing Advanced Search action (submit) button label: Labeling the button to submit searches as “Advanced Search” didn’t come across as an action label, likely because it’s a noun phrase and not a verb as “Search” is. This was noted by a JAWS-screenreader user who listened several times before deciding this was the action button.

Screenreader issues with the arrow indicators used to mark highlighted terms in proximity search results. In testing with this JAWS-screenreader user, we found that highlighted keywords in search results were read aloud as “Highlight number one marks <KEYWORD> End mark highlight number one” for each matched keyword, which was unexpected to the user, hard to interpret, and distracted from the listening experience. We are continuing to investigate alternatives to provide a better experience.

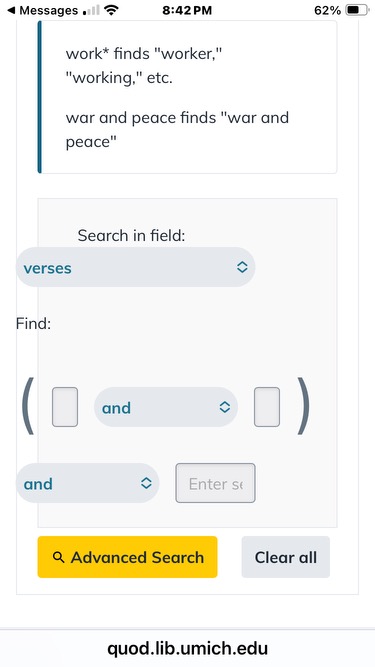

Frustrating presentation of Boolean search fields on mobile phones: One participant tested by mobile phone and found that, on smaller devices, the Boolean form fields resized too small to see what was typed. Additionally, the shrunken text boxes enclosed by oversized parentheses lost the appearance of form entry fields (see image below). Fortunately, this issue was quickly corrected.

A mobile phone screen displaying Boolean search options

What’s next

For the near term, our old version of the KJV will remain online until the underlying system used for hosting our digital collections is redone. At that point, findings from this round of testing will be used to improve functionality and align system behaviors with user expectations, as we migrate our digital collections into that new system.

Reflections and Gratitude

Performing usability tests is one of the most rewarding aspects of my work. These sessions provide an opportunity to connect with real people who use our systems, and they yield a wealth of information about what’s working (or not) in the design and implementation decisions we’ve made. This study was particularly rewarding because we were able to recruit frequent users who really knew the current site’s features well. Our participants also expressed a lot of gratitude that this resource was free to use, reliable, and accurate.

In kind I would like to express gratitude on behalf of our project team to all our volunteer participants for their time and insights about the KJV preview site. We look forward to continuing our support for access to this and other important, historical digital collections.

And, finally, a huge thank you to the members of the project team, Chris Powell and Roger Espinosa, who created the preview site, made it available for testing, and have begun implementing these recommendations.