Dr. Amir Salaree earned his PhD at Northwestern University in 2019 and is now a Research Fellow at the Department of Earth and Environmental Sciences at the University of Michigan. He is a geophysicist interested in learning about earthquakes, tsunamis, landslides, and storms among other forms of natural hazards. He started off as a seismologist, but became fascinated by other aspects of our planet’s behavior along the way.

In collaboration with Drs. Zack Spira and Yihe Huang, he deposited a data set entitled "Supporting Data for Solving a Seismic Mystery with a Diver's Camera" in Deep Blue Data, University of Michigan's data repository. This data underlies their journal article in Geophysical Research Letters titled "Solving a Seismic Mystery With the Audio From a Diver's Camera: A Case of Shallow Water T-Waves in the Persian Gulf". In this interview, he describes this research and why they decided to share this data set publicly.

What prompted you to conduct your research in this area?

I have always been fascinated by how much you can learn from unexpected, often trivial sources of information. In 2022, I came across a video recording from divers who had captured the moments during an earthquake while scuba diving in the Persian Gulf, and then shared it on social media as something cool to watch. While the video is indeed cool to watch, it made me think “Gee, this is a high-quality recording of actual sound waves from an earthquake in shallow water; something people have not looked at before!” So I kept watching it over and over to digest every piece of information regarding the earthquake itself. I then thought, what if we use recordings like this as a means to warn people quickly after coastal earthquakes? From there, things started to get interesting as we explored various techniques and possibilities.

For those not familiar with your field, what is the one thing you think is most important/interesting to know/unique about your work or your findings?

I think the take-home message from this work is that you don’t necessarily need fancy instruments to do science, and perhaps more importantly warn people against earthquake hazard. Earthquake monitoring is – perhaps rightfully so – often considered as a complex process requiring significant amounts of data. However, we have shown the possibility of contributing to this process using simple, low-cost entertainment-grade instruments.

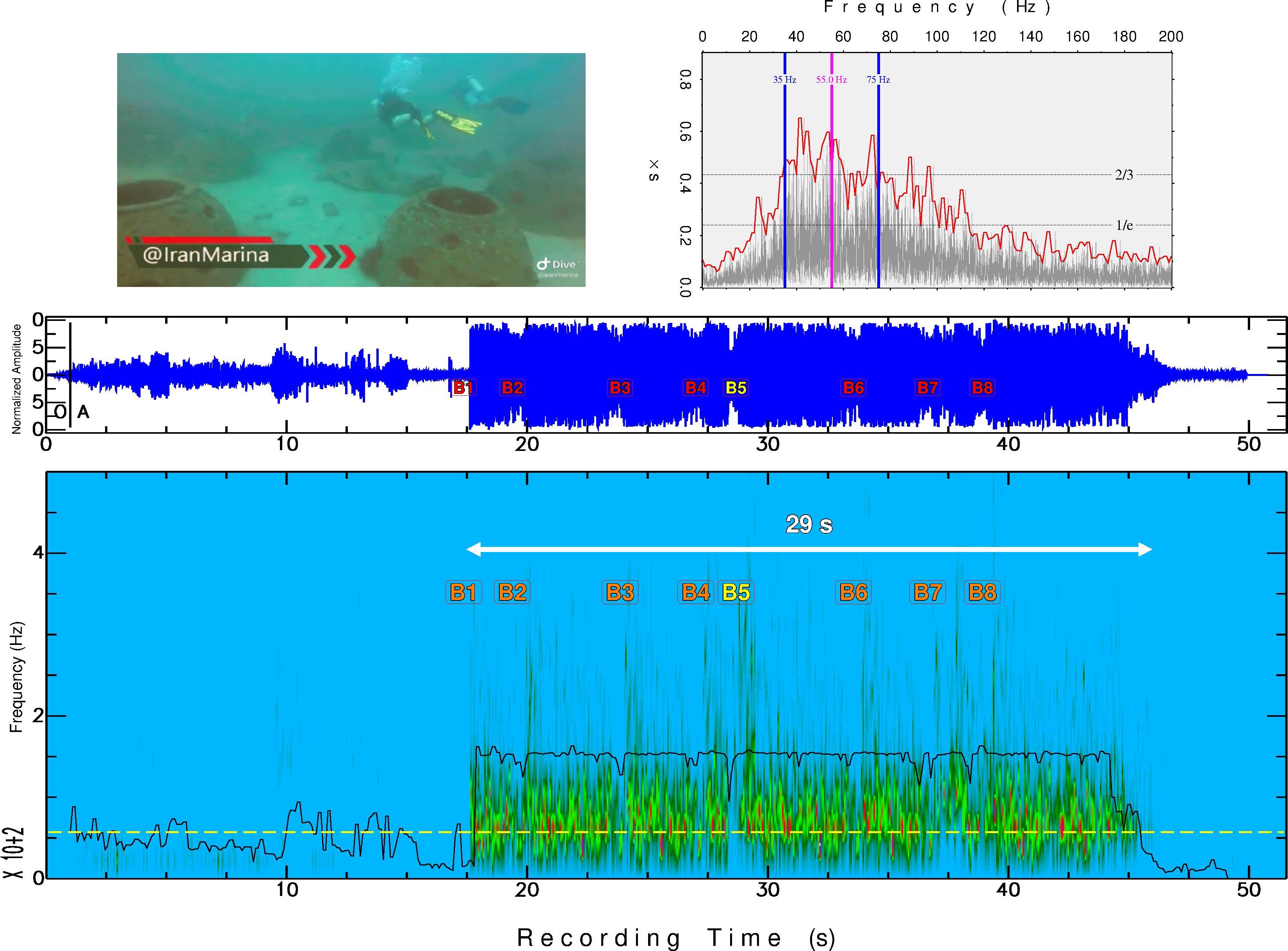

This figure from Dr. Salaree's article shows a screenshot of the video (upper left panels) and processed acoustic wave data (all other panels).

How do you hope your data might be encountered or reused out in the world?

First, there is the scientific merit of the results we have shared: we hope for them to be picked up by both the scientists in the field and the early warning institutions whose business is to save lives. I think in a nutshell, our method is an effort towards building a more inclusive scientific community where scientists from developing societies with little or no access to expensive computational resources can also take part in the monitoring of earthquakes.

Second, in an effort to give back to where I have acquired the data, I have tried to produce engaging demos for broad audiences. I hope both the audio and visual aspects of our shared results can motivate people to think about both science and earthquake hazard.

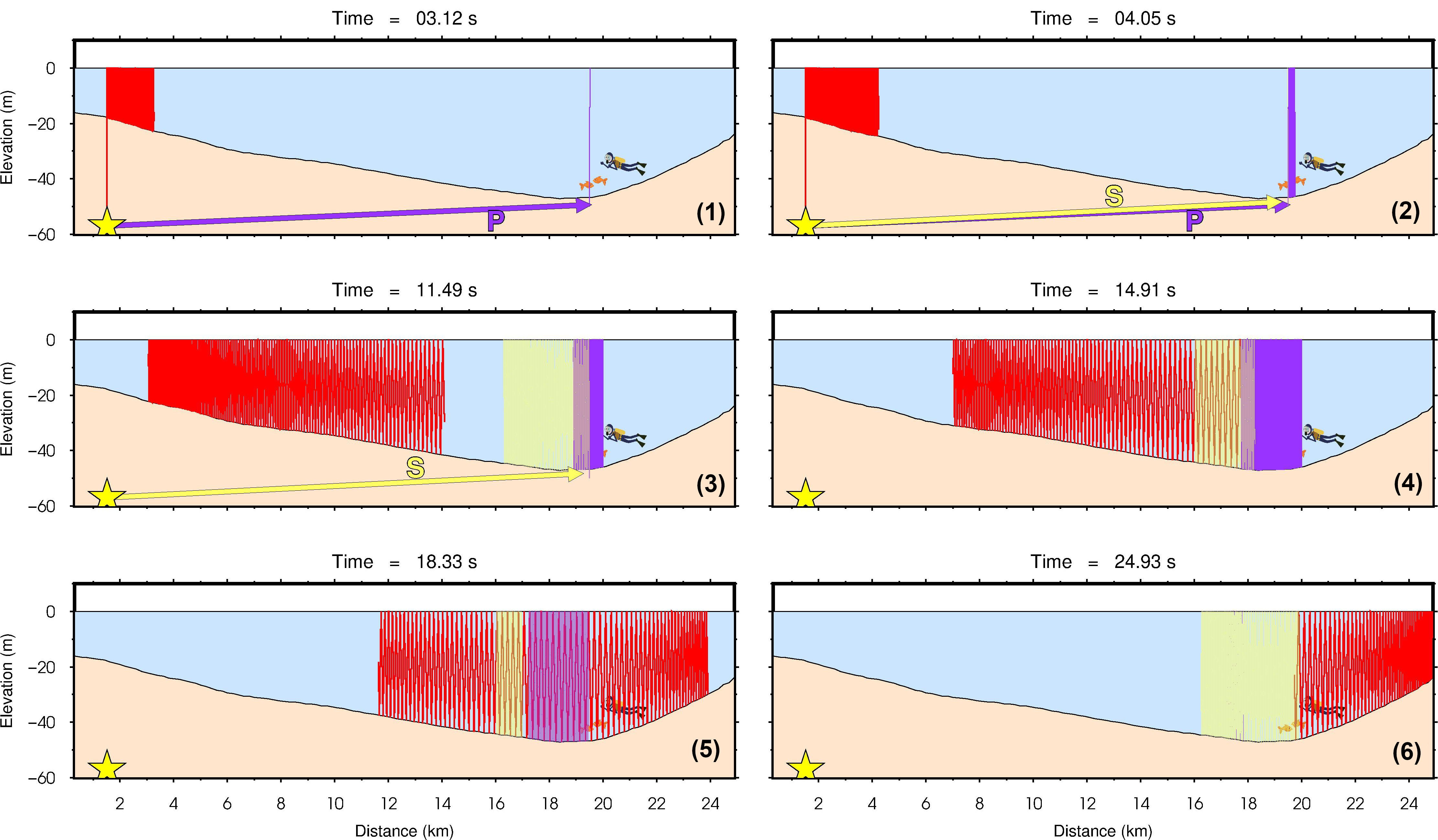

This figure shows the propagation of the acoustic waves generated by the earthquake, as determined by analyzing the diver's video.

What is one thing you learned during the process of preparing your data for deposit or sharing?

Self-contained packaging! I have found that while sharing data is important and must be straightforward, it by no means is a trivial process. Every bit of included information in a shared bundle matters, and the user must be able to find all the relevant pieces in what they get. I feel this is a tricky, but at the same time, rewarding process.

Why do you think sharing data is important?

I believe we have been shown over and over throughout history that humans as a species have prospered whenever they have shared knowledge and resolved the boundaries against it. While producing exclusive science can lead to profit, it will by and large slow down our progress as a species.