Comprised of nearly 75,000 books, serials, audio recordings, pamphlets, posters, photographs, political buttons, and archives, the Joseph A. Labadie Collection has been actively gathering together the words of social protest movements across America for more than a hundred years. Because of the remarkable temporal scope of this internationally renowned collection, it is possible to trace concepts and institutions that are now an integral part of modern society from their inception at the periphery of political thought through the long fight for enfranchisement and recognition to a point where their presence in everyday life seems a foregone conclusion. As of June 26, 2015, the same can be said for same-sex couples wishing to marry in the United States.

Last year, curator Julie Herrada and I highlighted some of the Labadie’s extraordinary LGBTQ artifacts in a display outside the Special Collections Reading Room in order to reveal the deep roots of this struggle in the American experience. In preparation for the one-year anniversary of Obergefell v. Hodges, I recently revisited the Labadie stacks looking for print manifestations of this revolutionary idea.

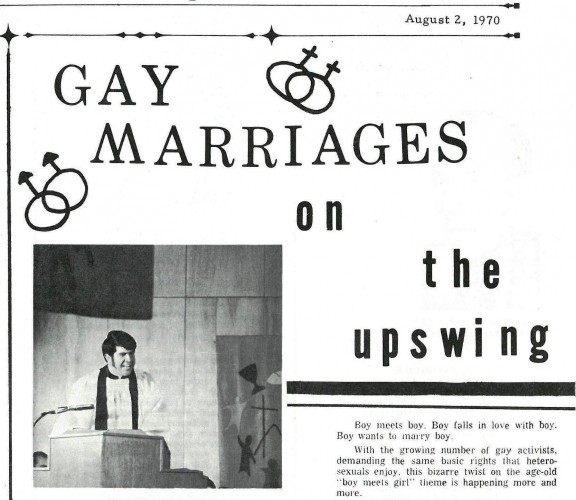

Items in June 2015 display case celebrating legalization of same-sex marriage in the United States

(see also http://u-mspcoll.tumblr.com/post/123636070572).

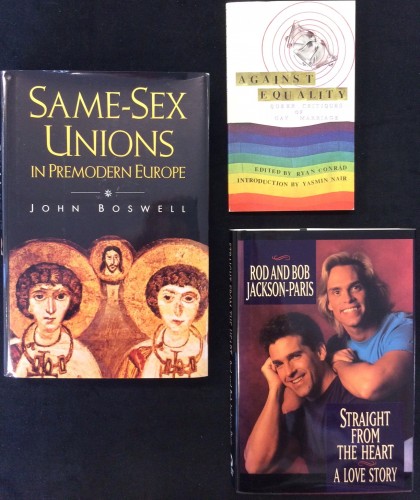

Boswell, John. Same-sex unions in premodern Europe.

New York: Villard Books, 1994.

Conrad, Ryan and Nair, Yasmin, eds. Against equality: queer critiques of gay marriage. Lewiston, ME: Collective, 2010.

Jackson-Paris, Rod and Paris, Bob. Straight from the heart: a love story. New York: Warner Books, 1994.

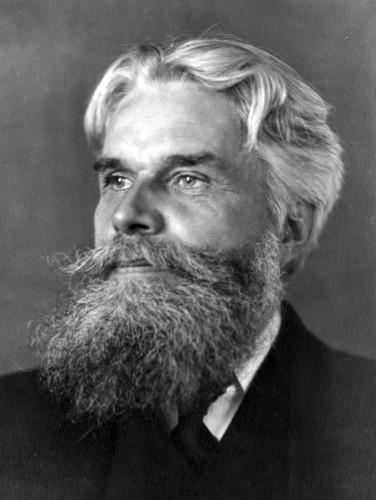

To begin with, I discovered that we have the Victorians to thank for our modern notions of sexuality. Springing from the late 19th-century psychology craze, self-styled “sexologists” sought to quantify, categorize, and, in many cases, pathologize the wide range of human sexual expression they observed through medical case studies. Coined in 1892, the term “homosexuality” came to be applied to subjects’ self-identities as opposed to their behaviors. Havelock Ellis authored the first (translated) English medical text devoted specifically to this new concept in 1897.

[Havelock Ellis, 1859-1939, head-and-shoulders portrait, facing left]. Original from Library of Congress.

Operating under the assumption that “female inverts” naturally felt inclined to adopt masculine modes of dress and comportment, Ellis later lent his support to Radclyffe Hall’s tragic 1928 Lesbian novel The Well of Loneliness, in which the masculine heroine, self-described “invert” Stephen Gordon, is haunted by her failed relationship with the callously inconstant Angela Crossby. In Ellis’ commentary on the novel, he praised Hall for crafting a story of “notable psychological and sociological significance.” Ellis' prefacing contribution lent an air of scientific respectability to the novel, but not enough to avoid public outcry. Almost immediately following publication, The Well of Loneliness was banned in the United States citing obscenity violations, though it contained not a word of explicit sexual content. Ellis dropped out of the resulting trial as an expert witness for the defense. Even the idea of a fictional Lesbian marriage, it turned out, was enough to gravely offend the sensibilities of the American people. In court, the prosecuting attorney contended that in "a pure woman or even a young man of adolescence," Angela's query, "Could you marry me, Stephen?," would induce "libidinous thoughts... deprav[ing] him and corrupt[ing] him as he conjures up the picture which the writer of this book intends." [1]

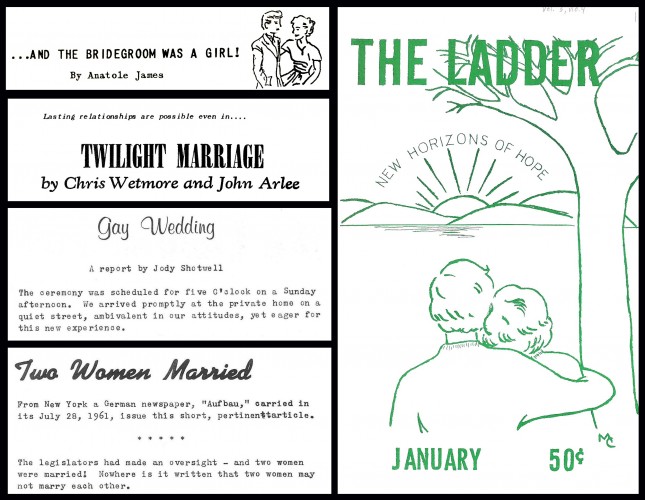

Although publications referencing homosexuality could still be prosecuted for obscenity under the Comstock Act until 1958, a small crop of limited-circulation serials aimed at gay men and Lesbians began to circulate throughout the country in the decades following The Well of Loneliness trial. Reports of same-sex marriages--as well as anti-marriage sentiment--appeared occassionaly in these plain-wrapper periodicals but were much outnumbered by articles concerning the legal and psychological ramifications of life as a homosexual in midcentury America. In June 1956, the Mattachine Review, one such pioneering magazine, ran a cover story titled “Twilight Marriage” prefaced with reassurances that this was to be a “frank report from two adult men” about how they came to establish a “permanent private life relationship.” [2] The term “marriage,” it is worth noting, appeared nowhere else in the article except the title.

From left to right:

Anatole James, "...And the Bridegroom was a Girl!"

Mattachine Reveiw 1 no. 3 (1955), 38.

Chris Wetmore and John Arlee, "Twilight Marriage,"

Mattachine Review 2 no. 3 (1956): 6-12.

Jody Shotwell, "Gay Wedding," The Ladder 7 no. 5 (1963), 4-5.

"Two Women Married," The Ladder 5 no. 12 (1961), 2.

The Ladder 3 no. 4 (1959)

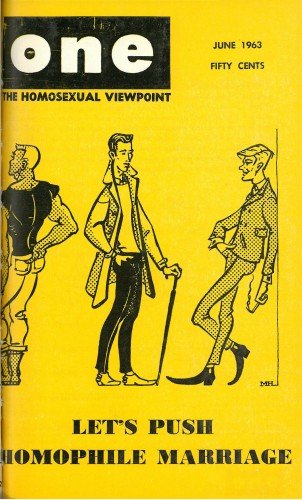

Seven years later, One (“The Homosexual Viewpoint”) published an article titled “Lets Push Homophile Marriage,” urging gay men to actively search for lifelong partners and offering dating and relationship advice. The author, writing under the pseudonym Randy Lloyd, decried the difficulty of searching out a life-partner under conditions that made it trying for gay men to gather and identify one another. On top of that, he acknowledged, “it would be a very rare homophile marriage that did not have on one side or the other some good reason for shunning publicity,” thus decreasing the likelihood of marriage-minded homophiles finding relationship role models. However, the long-term advantages of married life would pay off in the end, he asserted: “when society finally accepts homophiles as a valid minority with minority rights, it is going first of all to accept the married homophile. We are, after all, the closest to their ideals.” Furthermore, for those who “ridicule what they call the ‘heterosexual’ institution of marriage,” Lloyd simply responded, “I am a human being, male and married to another male; not because I am aping heterosexuals, but because I have discovered that is by far the most enjoyable way of life for me.” [3]

One 11 no. 6 (1963)

To be sure, many within the early Homophile Movement of the 50s and 60s as well as later battles for LGBTQ rights rejected the necessity or even legitimacy of same-sex marriages. During the Sexual Revolution, Don Milligan posited in his 1973 socialist pamphlet The Politics of Homosexualitythat “homosexuality breaks the rules, it is seditious and unnatural because it runs counter to the family and the fundamental values of capitalist society.” In Milligan’s capitalist society, the family must equate to “the man in charge, a subordinate woman, and their children on whom they imprint themselves,” thus making same-sex marriages a “grisly parody of heterosexual ceremonies. Far from making homosexuality acceptable, they demonstrate the absurdity of marriage and challenge the assumptions that the institution rests upon.” Instead, Milligan proposed establishing communes as the basic social unit, allowing for fluid relationship formation and kinship bonds. [4]

For those attempting to establish more conventionally bounded unions within the context of same-sex relationships, the practical concerns of living without a social safety net stealthily crept into every corner of their daily lives. Speaking before the second annual Symposium on the Life Style of the Homosexual held by the Council of Religion and the Homosexual in San Francisco, California, Robert W. Anderson gave a stirring keynote address titled Gay Marriage Between Two Males in which he recounted his happy 13-year marriage to his husband and wrestled with a concrete definition of marriage divorced from procreation and biological sex. After extolling the virtues of married life for several pages, Anderson finally came to the dénouement of his presentation. His tone turned bitter, reminding his audience that

The gay family doesn’t have the benefits of income-splitting for tax purposes. We don’t have special inheritance and gift tax exemptions. I can’t have my lover’s medical problems covered by my employer’s group health insurance... In view of all this, would I change? No, I’ve got my guy and he’s got me “for better or for worse,” you might say. I say our marriage has been for the better, a lot better! [5]

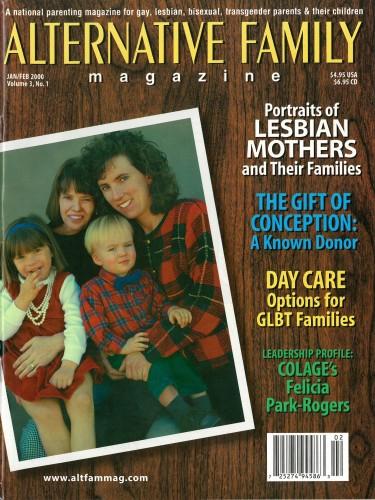

Alternative family magazine: a national parenting magazine for gay, lesbian, bisexual, transgender parents & their children

3 no. 1 (2000).

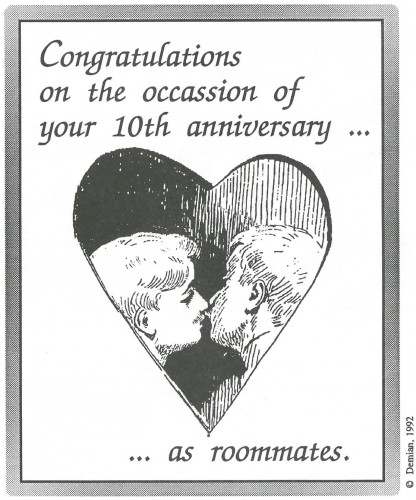

Throughout the 1980s, agitation for publically-recognized same-sex marriages and the legal concessions that accompanied them continued to grow within the LGBTQ community. Ignited in part by the so-called "Lesbian baby boom" of this and subsequent decades, the issue quickly grew into an integral part of the gay rights platform. Changing gender roles, the enduring effects of the Sexual Revolution, and a creeping public tolerance for gay visibility all helped fan the flames. Primed by over a decade of highly publicized protests and pride parades, the American public was forced to meet the gay front as a group with purchasing power and political might. Satirical images such as the one below likewise reflected a growing frustration with the perceived hypocrisy of a society that grudgingly acknowledged the existence of gay relationships but insisted on the fig-leaf of euphemism and innuendo in public discourse.

"Closeted couples forfeit support," Partners 7 no. 1 (1992).

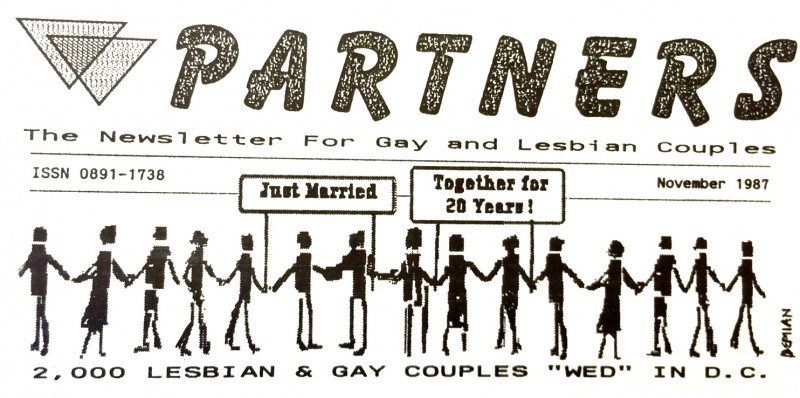

During this period, domestic partnerships, commitment ceremonies, and civil unions proliferated as marriage alternatives even as clamor increased for access to the full set of protections claimed by heterosexual couples. On October 1, 1989, Denmark became the first country in the world to offer "registered partnership" rights, which were equal under the law to those granted by marriage. Beginning in the early 21st century, the term "marriage equality" began to find adoption as a cause celebré of the LGBTQ community even as pushback from conservative political groups resulted in the passage of bills such as the Defense of Marriage Act and "Don't Ask, Don't Tell." While a long road lay ahead to the landmark Supreme Court decision of one year ago, a new paradigm of public, politically powerful gay relationships had emerged in the closing years of the second millennium, forcing heterosexual America to acknowledge and relate to same-sex couples in a manner that Victorian sexologists could never have predicted.

"2,000 Lesbian and gay couples 'wed' in D.C.,"

Partners Nov. 1987.

[1] Noble, Jean Bobby. Masculinities Without Men? Female Masculinity in Twentieth-century Fictions (Vancouver: UBC Press, c2004): 24.

[2] Wetmore, Chris and Arlee, John. “Twilight Marriage.” Mattachine Review 2 no. 3 (June 1956): 6.

[3] Lloyd, Randy. “Let’s Push Homophile Marriage.” One 11 no. 6 (June 1963): 6.

[4] Milligan, Don. The Politics of Homosexuality (London: Pluto Press, 1973): 4.

[5] Anderson, Robert W. Gay Marriage between Two Males (San Francisco: Council on Religion and the Homosexual, 1971): 5.