post authored by Lori Eaton

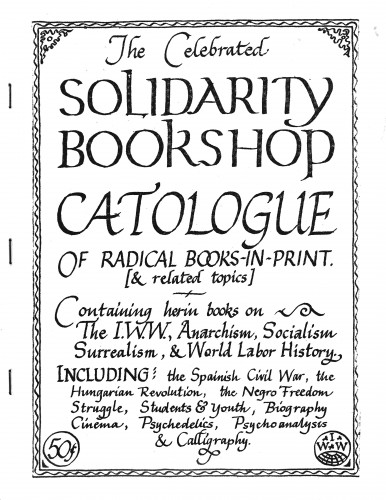

By the time they met in a class called “Social Disorganization” at Roosevelt University in 1964, Franklin Rosemont and Penelope Bartik were each set on a path toward radical thought, action, and art. Penelope, newly arrived in Chicago, was drawn to the city in search of a more authentic flavor of radical than the beatniks she had left behind at Lake Forest College in Lake Forest, Illinois. Franklin had been at Roosevelt for two years by then, and along with Tor Faegre and Robert Green, was just setting up the Solidarity Bookshop, a hangout for Chicago anarchists and surrealists selling all manner of radical literature. Together, they blazed a surrealist trail through the city and beyond for the next 45 years.

At the Solidarity Bookshop on Armitage Avenue, Franklin, Penelope, and their comrades printed the Rebel Worker and other pamphlets promoting workers’ rights on a mimeograph machine borrowed from the Industrial Workers of the World hall. They marched in the Mother’s Day peace rally of 1965, where they sold “Make Love Not War” buttons the bookshop had printed. A few days later, on May 13, Franklin and Penelope were married at a Unitarian Church in Chicago, with “no parents, friends, fuss, ceremony, etc.”

Issue 6 of the Rebel Worker, cover by

Charles Radcliffe, May 1966

It wasn’t long before their exploration of surrealism—and the role of the unconscious mind in art, creativity, and life—drew the Rosemonts to Paris where they met Man Ray, Ted Joans, André Breton, and other members of the Paris Surrealist Group. The Rosemonts returned from Paris “determined to start a specifically surrealist activity and publish a surrealist journal” with their comrades at Solidarity Bookshop. The publication of Surrealism & Revolution and The Forecast is Hot! were among the first results.

Cover of a Solidarity Bookshop catalog, ca. 1967

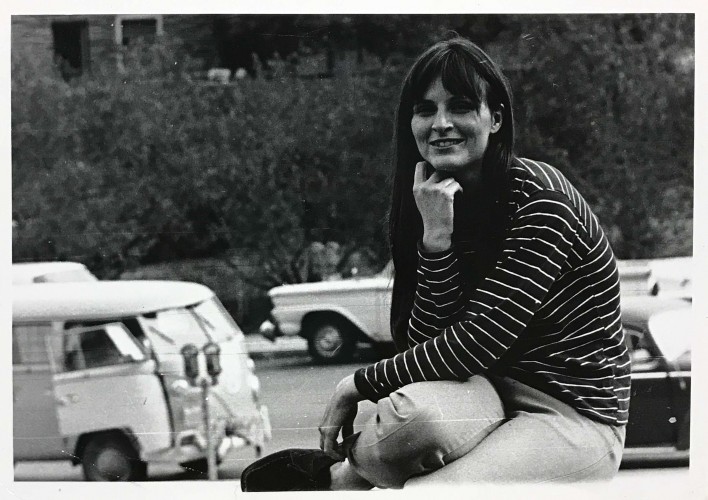

The Rosemonts joined the Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) and participated in the 1968 Democratic National Convention demonstrations in Chicago. Penelope hired on at the SDS print shop, while Franklin took a job at Barbara’s Bookstore on Wells Street in Lincoln Park where, according to Penelope’s memoir manuscript, the bookstore was packed on weekends. “Wells Street in the ‘60s was teeming with people. Friday, Saturday and Sunday, huge crowds of people could think of nothing better to do than walk down one side of the street from North Avenue to Barbara’s Bookstore and up the other; everything was open to midnight or later.”

Penelope Rosemont at an SDS meeting in Boulder, CO, 1968

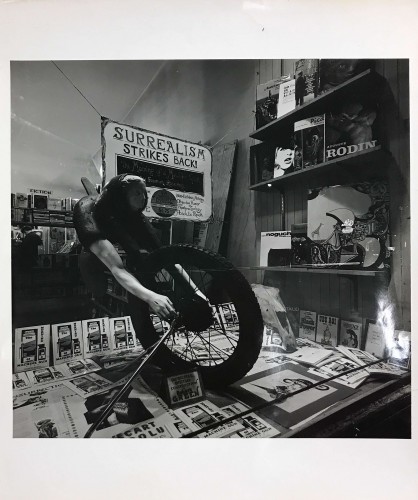

Barbara’s Bookstore window display featuring a

Robert Green sculpture, 1968

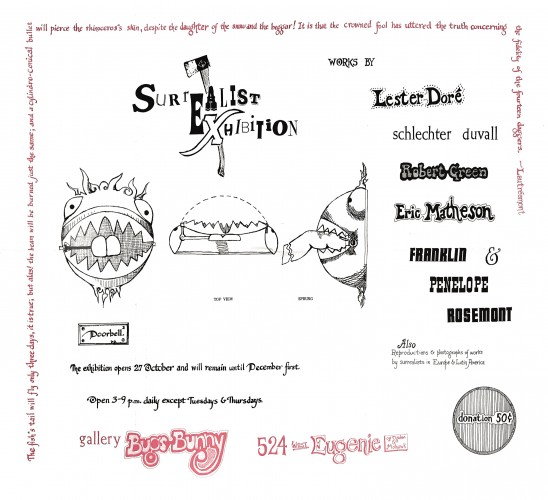

Robert Green and Franklin launched Gallery Bugs Bunny in a rented storefront at Eugenia and Mohawk streets. There was no sign out front—just a painting of Bugs Bunny, a sort of club mascot, on the door. The gallery’s first surrealist exhibition, held in the fall of 1968, was a group show featuring the work of Robert Green, Schlechter Duvall, Eric Matheson and both Rosemonts. Later, the Rosemont’s and their artist comrades organized the World Surrealist Exhibition in Chicago, drawing an international cast of characters.

Gallery Bugs Bunny exhibition poster, 1968

Franklin Rosemont with his surrealist sculpture, included in the Gallery Bugs Bunny exhibition, 1968

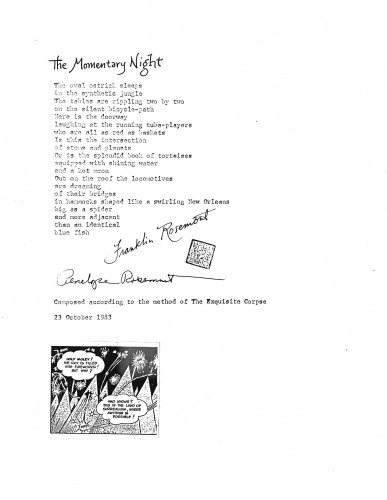

After a second trip to Paris in 1970, the Rosemonts returned home and began publishing their journal Arsenal with the help of Paul Garon. To combat misinformation about surrealism, they started Black Swan Press, Surrealist Editions, and the Surrealist Research & Development Monograph Series. The Chicago Surrealist Group attracted new members, and the Rosemonts’ connection to other surrealist groups around the world increased. The Rosemonts also published surrealist poetry, their own as well as others. In 1978, the Rosemonts joined the board of directors of Charles H. Kerr Publishing Company, the oldest radical publishing company in the world, and in 1983, Franklin Rosemont became chair of its publishing group.

Poem by Franklin Rosemont, 1983

By the mid 1980s, the center of the surrealist movement in Chicago shifted north to Rogers Park and the Rosemont home. From here, Franklin and Penelope and their comrades continued to write and publish and live out their surrealist ideals. The Labadie Collection’s Franklin and Penelope Rosemont Papers document their commitment to this way of life through notebooks, exhibition notes, photographs, unpublished manuscripts, and three extensive series of correspondence that include texts and original artwork from many individuals and groups.

As this remarkable collection has yet to be fully processed, contact the curator with any questions.