The exhibit Shakespeare on Page and Stage: A Celebration (Audubon Room, January 11-April 27, 2016) showcases both the textual and performance history of Shakespeare’s plays. This post looks at a particularly dramatic instance of Shakespeare forgery.

When William Shakespeare died on April 23, 1616, his work was sufficiently respected that within seven years, his fellow actors, John Heminge and Henry Condell assembled and published the First Folio. The First Folio’s significance is difficult to overstate - not only is it the earliest surviving source of many Shakespeare plays, it was the first collection consisting entirely of English plays to be published as a folio - a large and costly format that clearly marked its contents as worthy of serious attention. Nonetheless, Shakespeare was not then the legendary icon of English literature that he later became. And it is perhaps for this reason that so few traces remain of Shakespeare’s life as he lived it, for not even his friends and admirers thought to preserve drafts, letters, or other documents for posterity.

This absence in the historical record has, at certain times, provided an irresistable opportunity for literary forgers, with one of the most infamous incidents occuring in London in the 1790s. Enter from stage left William Henry Ireland, the son of publisher and avid Shakespeare collector Samuel Ireland. Samuel and William Henry Ireland had a relationship that was strained at best, and as a young man, William Henry wished desperately to please and impress the elder Ireland. And indeed Samuel Ireland was very pleased when his son began bringing home manuscript material in Shakespeare’s hand, supposedly from the home of a gentleman who wished to remain anonymous.

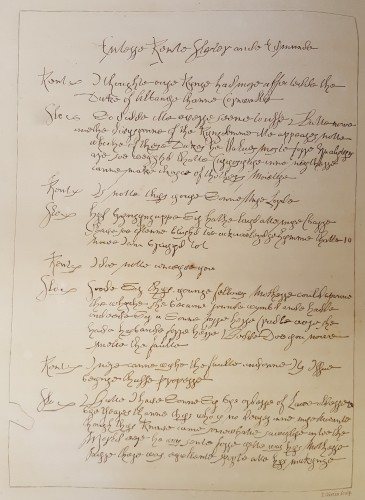

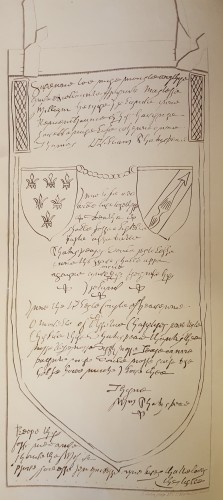

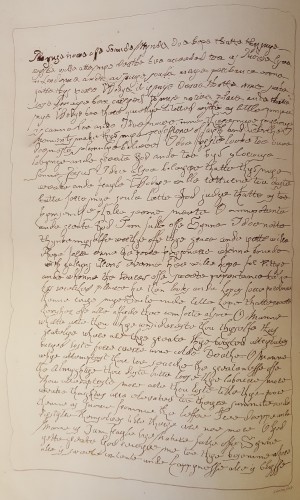

Forgery by William Henry Ireland, purporting to be a page from a manuscript draft of King Lear. Reproduced in facsimile in Miscellaneous papers and legal instruments under the hand and seal of william Shakespeare : including the tragedy of King Lear and a small fragment of Hamlet, from the original mss. in the possession of Samuel Ireland, of Norfolk street. London : Mr. Egerton [etc.], 1796.

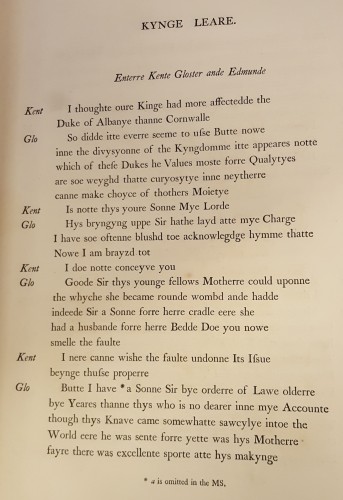

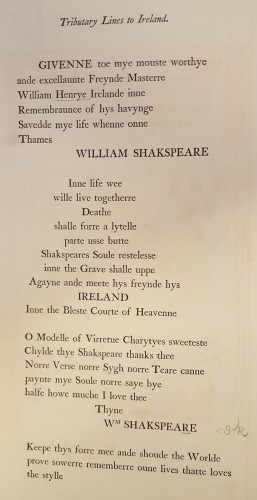

Transcript of the above from Miscellaneous papers and legal instruments under the hand and seal of william Shakespeare : including the tragedy of King Lear and a small fragment of Hamlet, from the original mss. in the possession of Samuel Ireland, of Norfolk street. London : Mr. Egerton [etc.], 1796.

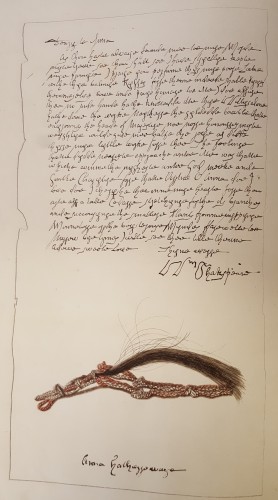

The initial manuscripts were authenticated by several experts of the time, including James Boswell, and Samuel Ireland reveled in displaying these treasures. Responding to Samuel’s and the public’s hunger for Shakespeare, William Henry produced more and more forgeries, making use of genuinely antique papers that he had access as a mortgage lawyer's apprentice and further "aging" them with the use of a candle. Among his efforts were a deed with Shakespeare’s signature, a promissory note, annotated books, suspiciously informal correspondence from the earl of Southhampton and Queen Elizabeth I, manuscript leaves of Hamlet and King Lear, and a love letter to his wife, accompanied by a lock of hair.

Forgery by William Henry Ireland, purporting to be a letter and lock of hair from Shakespeare to his wife Anne Hathaway. Reproduced in facsimile in Miscellaneous papers and legal instruments under the hand and seal of william Shakespeare : including the tragedy of King Lear and a small fragment of Hamlet, from the original mss. in the possession of Samuel Ireland, of Norfolk street. London : Mr. Egerton [etc.], 1796.

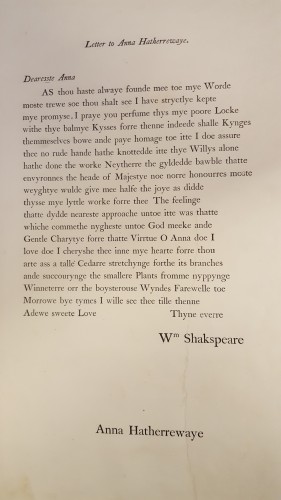

Transcript of the above from Miscellaneous papers and legal instruments under the hand and seal of william Shakespeare : including the tragedy of King Lear and a small fragment of Hamlet, from the original mss. in the possession of Samuel Ireland, of Norfolk street. London : Mr. Egerton [etc.], 1796.

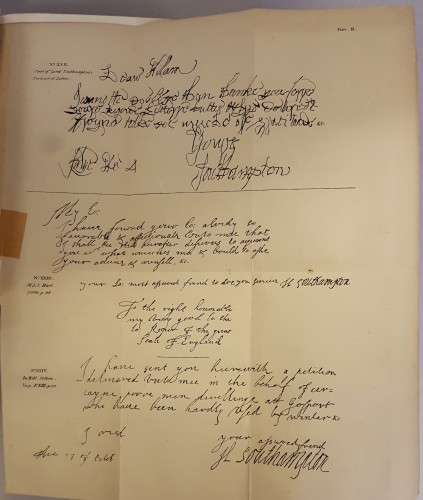

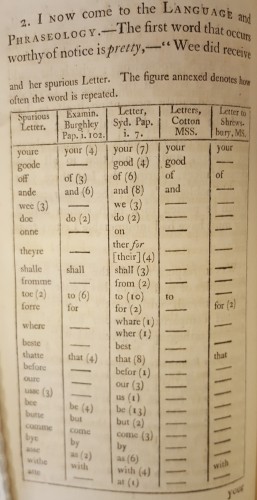

Many of these forgeries were reproduced in facsimile as part of Samuel Ireland’s Miscellaneous Papers and Legal Instruments under the Hand and Seal of WIlliam Shakespeare. This publication allowed closer, ongoing scrutiny of the documents’ appearance and content, undoubtedly hastening the inevitable exposé as questions of the documents’ authenticity were raised in public debate. There was much to question, for William Henry’s forgeries were poorly researched and painfully amateurish. The spelling, phraseology, and style were inaccurate. The handwriting and signatures of individuals such as the Earl of Southampton, whose writing appeared in extant documents, did not match. The content and self-referentiality of the documents were also sometimes suspicious, as when Shakespeare credits an Ireland ancestor with saving his life.

Forgery by William Henry Ireland, purporting to credit an ancestor of the Irelands with saving Shakespeare's life. Reproduced in facsimile in Miscellaneous papers and legal instruments under the hand and seal of william Shakespeare : including the tragedy of King Lear and a small fragment of Hamlet, from the original mss. in the possession of Samuel Ireland, of Norfolk street. London : Mr. Egerton [etc.], 1796.

Transcript of the above, from Miscellaneous papers and legal instruments under the hand and seal of william Shakespeare : including the tragedy of King Lear and a small fragment of Hamlet, from the original mss. in the possession of Samuel Ireland, of Norfolk street. London : Mr. Egerton [etc.], 1796.

Also in 1795, William Henry produced his ultimate forgery - a supposedly undiscovered Shakespeare play entitled Vortigern and Rowena, to which playwright Richard Brinsley Sheridan acquired production rights for Drury Lane Theater. It opened to widespread derision on April 2nd, 1796, just after Edmond Malone published a scathing point-by-point denouncement of Ireland’s forgeries as An Inquiry into the Authenticity of Certain Miscellaneous Papers… marking the beginning of the end for William Henry Ireland.

Facsimile of a forged Ireland letter, purportedly from the Earl of Southampton compared to facsimiles of two examples of his writing accepted as genuine, from Edmond Malone's 1796 An inquiry into the authenticity of certain miscellaneous papers and legal instruments, published Dec. 21. MDCCXCV, and attributed to Shakspeare, Queen Elizabeth, and Henry, earl of Southampton: ... London, Printed by H. Baldwin, for T. Cadell, jun. [etc.]

Table demonstrating the inaccuracy of Ireland's orthograpy by comparing the incidences of certain spellings in his forged letter purported to be written by Elizabeth I with genine documents in her hand, from Edmond Malone's 1796 An inquiry into the authenticity of certain miscellaneous papers and legal instruments, published Dec. 21. MDCCXCV, and attributed to Shakspeare, Queen Elizabeth, and Henry, earl of Southampton: ... London, Printed by H. Baldwin, for T. Cadell, jun. [etc.]

Adding to the pathos, Samuel Ireland initially refused to believe William Henry’s confession, not because of faith in his son’s good character, but because he did not believe him to be clever enough for such a scheme. Unfortunately for Samuel, despite William Henry’s multiple published confessions, many critics agreed that someone else was at the root of the scam...and often claimed that someone was Samuel Ireland himself, permanently ruining his reputation.

An Authentic Accoung of the Shaksperian Manuscripts, &c. (1796) by William Henry Ireland. Printed for J. Debrett.

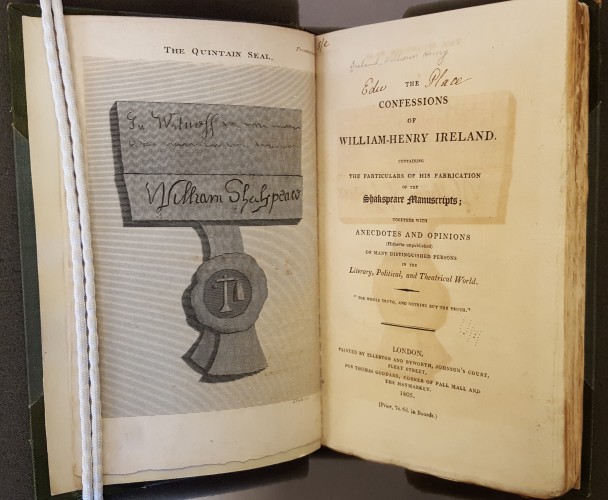

The confessions of William-Henry Ireland: containing the particulars of his fabrication of the Shakspeare [sic] manuscripts. London... (1805) by William Henry Ireland. Printed by Ellerton and Byworth, for T. Goddard.

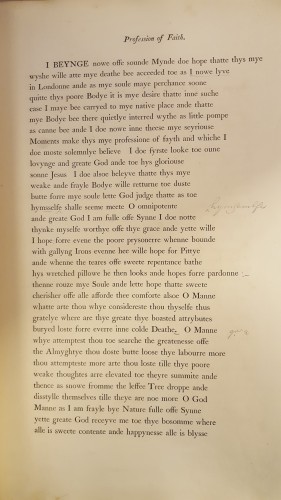

Given their obvious errors and suspect content, why did William Henry Ireland’s forgeries succeed at all? Certainly, the fact that, at first, the manuscripts could only be observed briefly and under Samuel Ireland’s watchful eye was a key factor. However, the timing was also significant. Shakespeare’s reputation and symbolic importance had grown exponentially over the course of the 18th century, alongside nostalgia for “Old England.” At that point, Shakespeare had been dead not quite 200 years - scholars and collectors were hoping and actively seeking to discover just these kinds of materials - thus, their instinctual reaction was not immediate disbelief, but of expectations fulfilled. Additionally, in certain key ways, William Henry depicted a Shakespeare in keeping with the 18th century picture of a model Englishman - staunchly protestant, in love with his wife, and on easy terms with the rich and powerful. It was a Shakespeare that Londoners in the 1790s wished very much to believe in.

Forgery by William Henry Ireland, purporting to be a solidly protestant profession of faith by Shakespeare. Reproduced in facsimile in Miscellaneous papers and legal instruments under the hand and seal of william Shakespeare : including the tragedy of King Lear and a small fragment of Hamlet, from the original mss. in the possession of Samuel Ireland, of Norfolk street. London : Mr. Egerton [etc.], 1796.

Transcript of the above from Miscellaneous papers and legal instruments under the hand and seal of william Shakespeare : including the tragedy of King Lear and a small fragment of Hamlet, from the original mss. in the possession of Samuel Ireland, of Norfolk street. London : Mr. Egerton [etc.], 1796.