In Special Collections, our books don’t leave the building, but sometimes the recipes sneak out for a trip to the kitchen. Last week, the U-M Library Art Alliance (a staff interest group), the William L. Clements Library, and the Special Collections Research Center teamed up with Student Life Sustainability for a small, hands-on staff event, where we brought two nineteenth century cookie recipes to 21st century tastebuds.

For this historical cooking experience, we prepared a recipe titled simply “Cookies” from the Washington Sarah Dunkin Washington Cookery and Confectionary Book from the William L. Clements Library, and a “Ginger Cake” recipe from Dr. Chase's recipes; or, Information for everybody… in the Janice Bluestein Longone Culinary Archive. For December’s Recipe of the Month, I’ll focus on Dr. Chase’s Ginger Cake, which in modern parlance is not a cake at all, but much closer to what we could call a cookie.

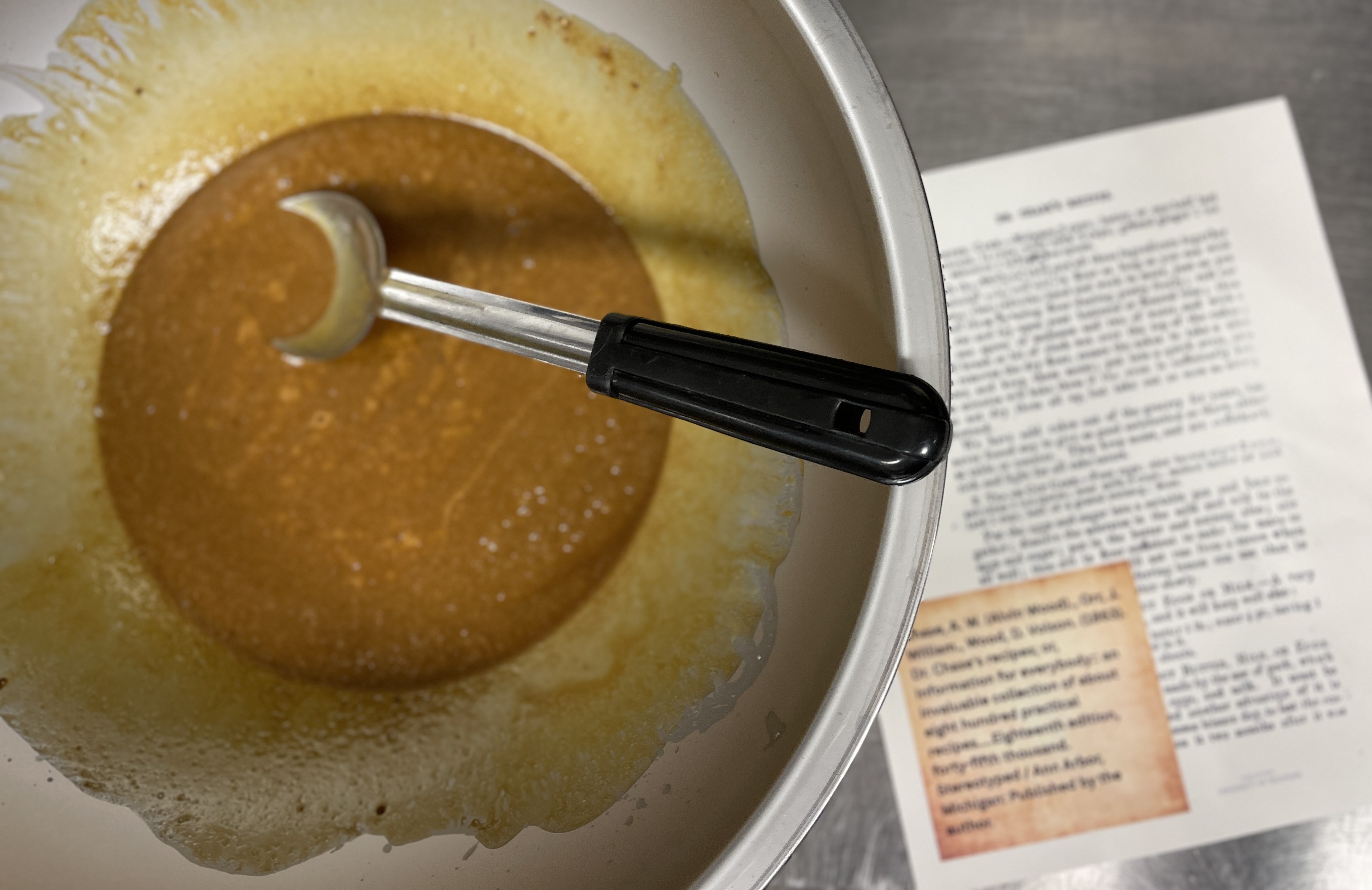

Ginger Cake - Molasses 2 cups; butter, or one-half lard if you choose 1 ½ cups; sour milk 2 cups; ground ginger 1 teaspoon; saleratus 1 heaping tea-spoon.

Mash the saleratus, then mix all these ingredients together in a suitable pan, and stir in flour as long as you can with a spoon, then take the hand and work in more, just so you can roll them by using flour dusting pretty freely; roll out thin, cut and lay upon your buttered or floured tins; then mix one spoon of molasses and two of water, and with a small brush or a bit of cloth wet over the top of the cakes; this removes the dry flour, causes the cakes to take a nice brown and keep them moist; put into a quick oven; and ten minutes will bake them if the oven is sufficiently hot. Do not dry them all up, but take out as soon as nicely browned.

In comparison to many 19th century recipes, this is actually fairly detailed, with specific amounts of (most) ingredients and directions for mixing, rolling, and baking. However, when actually making the recipe, a few questions arise:

- What is saleratus?

- How much flour should be used? This is the one ingredient for which no specific amount is given.

- When rolling the cookie dough, how thin is “thin?”

- How hot is a “quick” oven?

Questions 1 & 4 relate to changes in baking technology. Saleratus was a 19th century chemical leavening agent similar to baking soda and can be easily replaced by the modern version. In the case of oven temperature, Dr. Chase was writing in a time long before gas and electric stoves were common kitchen appliances. The first gas stoves were developed in the 1820s, but they did not become practical or common in America until the late 19th or early 20th century. Dr. Chase’s readers would have been cooking in ovens heated by wood or coal and would have relied on their own familiarity with lighting & maintaining fires to heat their homes & cook their food in order to identify an appropriate heat level for baked goods. Fortunately, there are rough conversions out there to help out a modern cook and a “quick oven” generally translates to 375-400 degrees Fahrenheit.

On the other hand, the only way to answer questions 2 & 3 was to do a little hands-on history in my own kitchen, prior to our public event. Recognizing that this recipe has a LOT of liquid - 2 cups molasses, 1 ½ cups butter, and 2 cups of sour milk - I could tell it would take a lot of flour. In my experiment, I halved the recipe, and even so, it took more than 6 cups of flour to obtain dough stiff enough to roll. That means the original required at least 12 cups!

In my quest for optimum cookie thickness, I rolled half my dough to ¼” and half to ⅛,” and cooked half of each of the resulting cookies at 375* and the other half at 400.* Personally, I liked the ⅛” cookies baked at 400* best (which required a baking time closer to 8 minutes) but some of my taste testers preferred the thicker, softer cookies.

The most notable thing about Dr. Chase’s gingerbread cookies is that there is no additional sweetener besides the molasses, reflecting the fact that in 1860s Michigan, sugar was still a luxury for many people. Compared to modern cookies, these taste barely sweet - almost savory - with a dry texture that makes them more like a thick, soft cracker or a thin biscuit than a cookie. Reactions from our fellow library staff varied from “This is awful and I need to get this taste out of my mouth!” to “These are amazing and I am obsessed!” Consider adding these to your holiday cookie rotation and see for yourself what your reaction will be!