In early April, we welcomed Cheryl Porter to campus for a lecture and 3-day workshop. Participants in the workshop included colleagues from the Special Collections Research Center, Library Preservation & Conservation, and Stamps School of Art & Design, along with several graduate students from the Department of History of Art. In this post, Marieka Kaye (Head of Conservation & Book Repair) offers us an overview of the workshop which explored the colors used by artists working in the Islamic and European traditions of the medieval era. All photos by Marieka Kaye.

As librarians, instructors, and conservators working for U-M, we are of course familiar with the magical quality of some of our earliest and most rare holdings – our medieval and Islamic manuscripts. It’s easy to get lost in the small painted and gilded details on the pages of finely made parchment or paper. What we don’t get to do as much is dive into how these exquisite pieces were actually made, from raw materials to the final product.

In early April 2019, Special Collections was fortunate to be able to welcome Cheryl Porter to the library to teach the workshop, Re-Creating the Medieval Palette. Cheryl is a world renowned book and paper conservator and the Director of the Montefiascone Conservation Project for over 30 years. She established this project in order to raise money to save a derelict medieval library in a small medieval Italian city, and in 1992 also established an international summer school with class offerings for librarians, conservators, catalogers, bibliographers, and those interested in the history of bookbinding. She is currently writing a book on the use of color in manuscripts for Yale University Press.

Cheryl Porter demonstrates the formation of a lake pigment during the workshop

In Cheryl’s workshop, participants were able to immerse themselves in the raw materials that were processed to make colors used by artists throughout the medieval era, mainly those working in the Islamic and European manuscript traditions. The materials explored in the class included rocks, minerals, metals, insects, and plants. Cheryl spent each morning providing extensive background information on the colors used to paint manuscripts, including chemical and physical properties, recipes, methods of manufacture, and economic and iconographic significance. Binding media was also examined, such as egg whites and gum arabic.

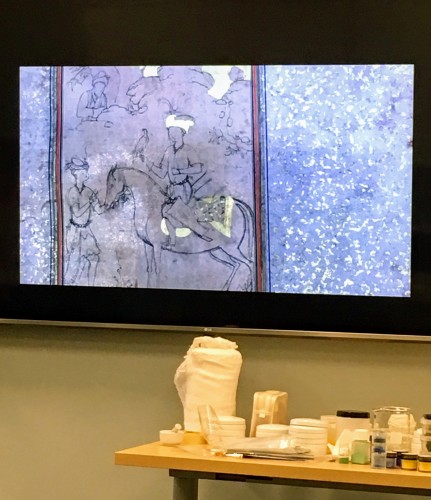

View from the morning lectures

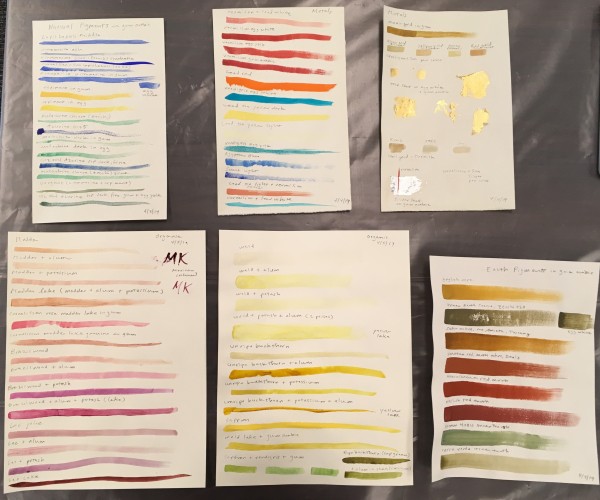

The afternoons were spent with hands-on practice and experimentation. Participants re-created colors using original recipes. Everyone was able to get a feel for the labor required to prepare pigments from their raw sources to their final application as paint. Samples were collected in the form of pigment charts, made by everyone to take away for future reference and analysis. Some of the samples re-created included earth and natural mineral colors, synthetic colors, metals, and organic “lake” colors - particularly focusing on yellow, green, red, and blue organics from plant and insect sources.

Sample charts created during the workshop

One of the most memorable parts of the course included using a glass pestle to grind a variety of dry pigments into a finer consistency that could then be mixed with egg white or gum arabic to give them the viscosity of paint. Some pigments were more difficult to grind and blend, and some were quite toxic, such as lead white, lead red, verdigris, and vermilion. Experiencing these trials and tribulations made the amount of labor that medieval artisans went through even more astounding.

Grinding pigments with glass pestle, then mixing

Additionally, participants were able to experience the sheer delicacy of applying thin gold and silver leaf to a mordant on paper. There was much holding of breath and moving at a sloth’s pace, so as not to disturb the delicate wisps of metal leaf as they were being lifted from a suede cushion to a fine brush and transferred to paper. Cheryl also provided a variety of metallic shell paints, such as various hues of shell gold reminiscent of those used in the Islamic manuscript tradition.

Working with gold & silver leaf (above) and shell gold (below)

The organic portion of the class was a bounty of odors, as participants explored the cooking down of saffron, brazilwood, buckthorn, and woad. There was much exploration of the subtleties of indigo, and how pH changes the quality of organic lakes and dyes. We also experienced the intensity of insect-based colors, which require painstaking collection methods. A favorite is the cochineal insect, which provides the most vibrant red lake pigment and dye. Cheryl allowed participants to scoop some soaked (and odoriferous) insect carcasses into little baggies for future reference and fun show-and-tells to entertain students and colleagues.

Dying alum tawed skin with brazilwood juice

Cochineal insects from Oaxaca, Mexico

The workshop provided an incredible opportunity to enter a different time and space, recreating the vibrancy we find in the manuscripts we love to study and admire. Cheryl emphasized that further pigment analysis is needed to add to our knowledge of medieval material history. Although sampling the real thing is a tricky proposition because we don’t want to interfere with our originals, it may be necessary for future discoveries so that we may continue to learn from and preserve these important records of human knowledge.

With thanks to the Special Collections Research Center and Department of Preservation and Conservation as well as the University of Michigan History of Art Department and the Interdisciplinary Islamic Studies Seminar for their sponsorship of Cheryl's visit.