One of the great pleasures of spending this summer in the archives as a Mellon Public Humanities Fellow has been stumbling into and out of people’s lives, or the echoes of them left behind in correspondence, records, doodles, drafts, and other materials. There are a lot of recognizable names in the Special Collections Library stacks, but for every person I’ve read or heard about there are so many more who are new to me.

The Joseph A. Labadie Collection’s Mary Hays Weik Papers (1921-1979) roughly outline the trajectory of Weik’s work as a journalist, writer, leading proponent of world government, and anti-nuclear activist. They follow her from the Chicago area to Cincinnati, where by the late 1940s she was becoming increasingly involved in (and would eventually lead) the American Federation of World Citizens (AFWC), and finally to New York, where she was as an accredited United Nations (UN) observer; the papers record the extensive international travel she undertook for her role at the AFWC, and her decades in New York, where she increasingly gravitated toward anti-nuclear activities and writing children’s fiction.

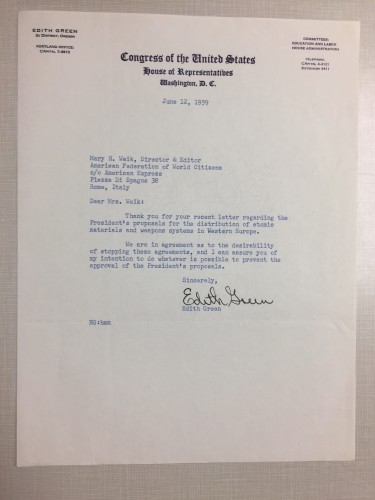

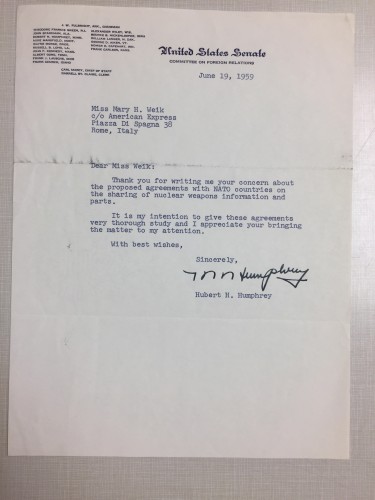

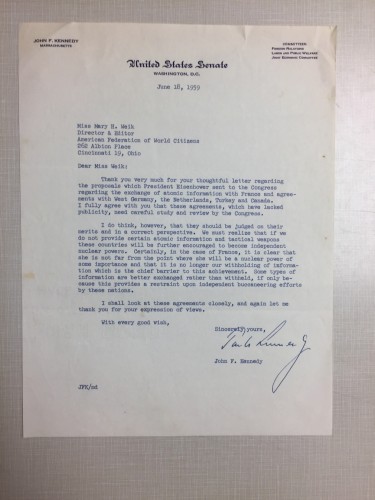

The papers show a lifetime of tireless work. Weik graduated from DePauw University in Greencastle, Indiana, and was a journalist through the 1920s and ‘30s while raising two children on her own. She moved to Cincinnati while her son attended graduate school there and became increasingly involved in local, national, and international peace activism. Correspondence gives us a window into her network as it grew in size, distance, and rank. By the late 1950s, Weik’s network was extensive, and her position as director of the AFWC assures that her correspondence varies from quotidian organizational matters, letters between friends, and lobbying officials in Washington and at the UN. From Italy in June 1959, Weik wrote to members of Congress to register her opposition to President Eisenhower’s proposal to share information on nuclear weapons with allied countries in Europe; we don’t have a draft of this letter, but we know it existed because we have some of the responses she received.

Letter to Mary Weik from Representative Edith Green (Photo courtesty of Rebecca Huffman)

Letter to Mary Weik from Hubert Humphrey (Photo courtesy of Rebecca Huffman)

Letter to Mary Weik from John F. Kennedy (Photo courtesy of Rebecca Huffman)

In this case, and in most cases, we only have some of the puzzle pieces available to us. The responses, our evidence of Weik’s letter to these representatives, start to fill out the shape of her activism. Her correspondence with other supporters of world government, a movement that peaked in the years between the Second World War and the Korean War, shades in more sides of that work. Some letter writers come and go, and some return as old friends in folder after folder, year after year. Often, we have only one side of that correspondence. The letters are the material remnants of affection and friendship, a record of the bonds Weik forged between people in her life.

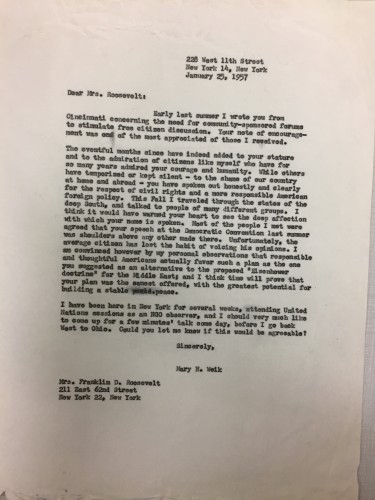

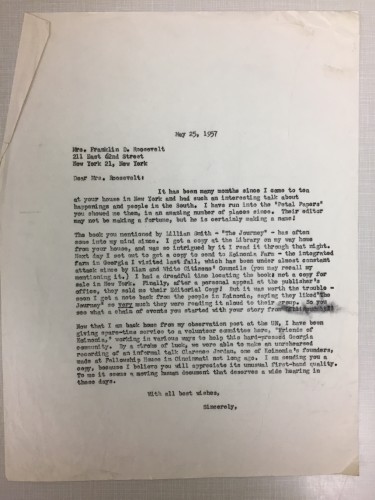

For me, those gaps are an invitation to possibility. I’m sharing my favorite gap here: a letter from one activist to another, one that seems to exist within the context of an ongoing, if occasional, correspondence. We don’t have Weik’s first letter to Eleanor Roosevelt, and we don’t have Roosevelt’s replies, but we have drafts of Weik’s second and third letters:

Letter to Mary Weik from Eleanor Roosevelt (Photo courtesy of Rebecca Huffman)

Letter to Mary Weik from Eleanor Roosevelt (Photo courtesy of Rebecca Huffman)

Between January and May 1957, while Weik was still in New York attending the UN, she and Roosevelt had what sounds like a fruitful discussion at Roosevelt’s home. Roosevelt recommended reading to Weik, who like Roosevelt was active in the Civil Rights Movement. Weik seems to have been bolstered by her meeting with Roosevelt, who was 14 years Weik’s senior, and who died five years after their meeting. I can’t tell you with any certainty if other letters from Weik to Roosevelt are extant, but these are the two we have in our collection— as for the rest, we’ll just have to explore the different ways we can connect the dots between them.

Working in the archives this summer has underscored questions I ask as a researcher about how historical narratives are made and who makes it into them. Acceptance into an archive helps determine the historical narratives we’ll tell about a period; this is raw material for the researchers who write those narratives. But archives themselves are also rich in the publicly available but less-well-known collections that haven’t emerged into broader public consciousness. My hope is that my work this summer will make those seemingly "hidden" collections at least a little less hidden.