The Special Collections Research Center is thrilled to announce the opening of our latest exhibit, “A Revolution Worth Having: Emma Goldman at 150,” on view on the 6th floor of Hatcher Graduate Library from June 3rd to August 1st.

This exhibit pays tribute to one of the most distinctive figures represented in our collection, and is dedicated to the memory of the friends and comrades who have nourished and sustained the relationship between Emma and the Labadie Collection over the years. The majority of the items on display are being exhibited to the public for the first time.

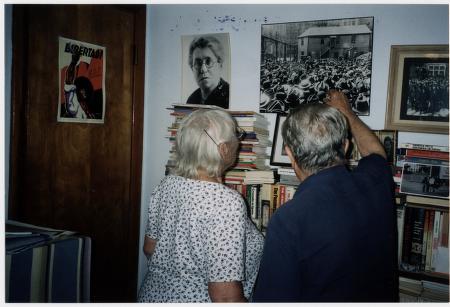

Federico Arcos and Audrey Goodfriend examine a photograph of Emma Goldman in Arcos’ home, 2003. Arcos received Goldman’s famous suitcase in the 1970s from Arturo Bortolotti and cared for it until his death in 2015, when it was transferred to the Labadie. Photo: J. Herrada

Goldman’s connection to the library dates back to at least 1906, when she first corresponded with Jo Labadie. Labadie’s personal collection of anarchist materials would eventually become the Joseph A. Labadie Collection under the stewardship of its first curator, Agnes Inglis. Goldman subsequently made several visits to Ann Arbor and Detroit, giving lectures and seeing her friend Inglis. Never one to hide her opinions, the famously cantankerous Goldman made her distaste for the area known. One 1911 newspaper headline read: “Anarchist Leader Tells What She Thinks of Detroit and Ann Arbor — ‘Pampered Parasites,’ She Calls Students; Roasts Weak-Hearted Radicals Here.” Inglis later reminisced in a letter to Goldman, “You said if you had to choose between living in Ann Arbor and going to jail, you would choose to go to jail.”

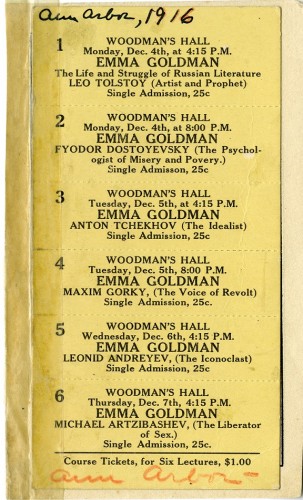

Tickets for a 1916 lecture series Goldman gave in Ann Arbor's Woodman's Hall, located on the corner of Washington and Main

Despite her general antipathy toward Michigan, Goldman had warm feelings toward Inglis and the Labadie. Writing from Paris in 1930, she told Inglis: “Alas, I shall never be able to see it, but just to know that such a thing exists and will be accessible to students of social thought is encouraging.” Although Goldman, living in exile from her adopted homeland, believed then she would never see the United States again, she was permitted to return for a 90-day lecture tour in 1934. After a lecture in Detroit, she made a separate trip to Ann Arbor to visit the Labadie Collection. Inglis wrote of this visit: “Emma was happy in her perusal of this most wonderful record of, not only her life’s interest bu in [sic] the record that meant so much to so many, many others... When she smiles and relaxes she is beautiful. Usually, however, she is intense and serious. And her face is sad.”

While Inglis was the only one of the Labadie’s three curators who knew Goldman personally, the special relationship between the Labadie and Goldman has endured to the present day. In 1997, current curator Julie Herrada and her predecessor Ed Weber traveled to Toronto together to visit Eva Langbord. Then in her late eighties, Langbord was the daughter of Goldman’s close Toronto comrades whom she had known in her later years. Langbord shared her memories of the many anarchist figures who had spent time at her parents’ house when she was a child, including Emma Goldman. After Goldman’s death in 1940 Langbord received many of her personal items, including her shawl she always wore while lecturing and a packet of personal papers and official documents she carried everywhere with her. Langbord told Herrada and Weber that these papers belonged in the Labadie, and so she gifted them to the collection.

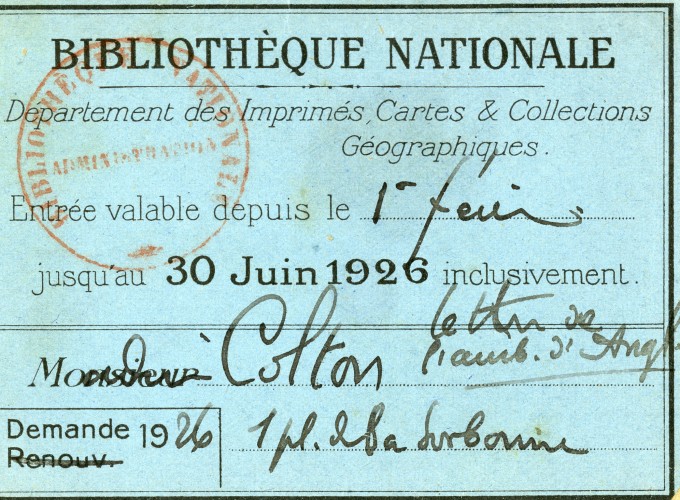

Goldman's libary card for the Bibliotheqe Nationale, issued in 1926. Her married name, Colton, is used

The “packet” is the source of several of the Labadie’s most moving Goldman artifacts. It contained, among identity documents from five other countries, the paper proving that Goldman had been naturalized as a U.S. citizen. Stripped of her citizenship and deported in 1919, Goldman kept this document with her for the rest of her life. Another document she cherished was the emotional letter from her lifelong friend and comrade, Alexander “Sasha” Berkman. Writing in 1917 as the pair sat in separate jails awaiting the court decisions that would eventually lead to their deportations, and determine the course of their lives from that point, Sasha told Emma:

You have been my mate and my comrade in arms, my life's mate in the biggest sense, and your wonderful spirit and devotion have always been an inspiration to me, as I'm sure your life will prove an inspiration to others long after both you and I have gone to everlasting rest... I know that whatever happens, you will remain the immutable in the strength of your spirit, in your passionate love of liberty and human welfare.

Sasha’s tribute to Emma is a testament to the devotion that she inspired among those who knew her.

We invite you to our exhibition space on the 6th floor of Hatcher Graduate Library to view this remarkable document (known as the “Letter from Tombs Prison”), along with other Goldman artifacts including her publishing contract with Alfred Knopf for Living My Life, her Soviet passport, and photographs of her famous suitcase (currently on traveling exhibition).

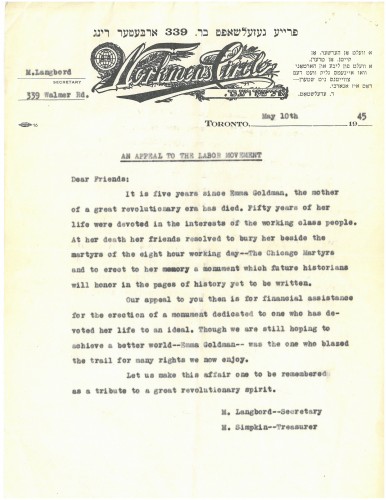

Goldman died in 1940 and was buried alongside the Haymarket Martyrs in Chicago's Waldheim Cemetery. Comrades around the world contributed money to erect a monument to her. This fundraising plea came from Morris Langbord, secretary of the Toronto Workmen's Circle.

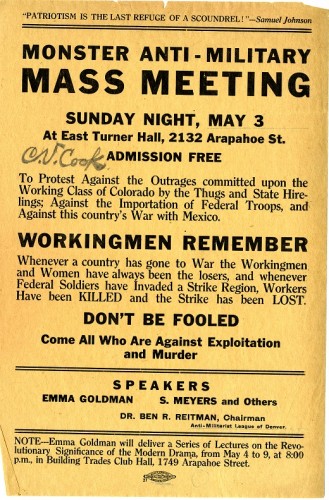

Flyer advertising an anti-war rally in May of 1914. Though World War I was looming, this meeting was concerned with the possibility of a war between U.S. and Mexico. Goldman was eventually arrested and deported due to her opposition to U.S. involvement in World War I

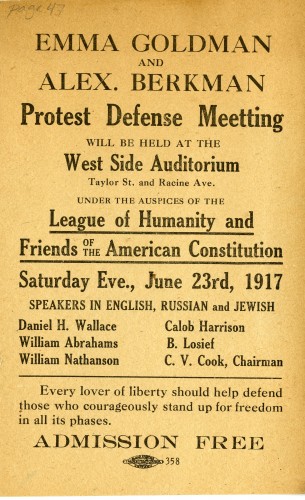

Palm card advertising a rally held in Chicago in defense of Goldman and Berkman, who in 1917 were facing deportation

"A Revolution Worth Having: Emma Goldman at 150" will be on display until 1st August in the Special Collections Research Center, Hatcher Graduate Library.