Sewing and needlework were strongly associated with femininity in the Georgian period. "Plain sewing" of shirts or other garments was considered an essential matrimonial duty (whether the wife held the needle herself, or simply sourced the linnen, selected the thread, and hired the seamstress). In Behind Closed Doors: At Home in Georgian England, Amanda Vickery notes that the need for new shirts is a frequent topic of letters to and from home by bachelors who relied on mothers and sisters for their sewing. Because clean linen was seen as a mark of decency and moral worth, an adequate (and adequately maintained) supply of white shirts was crucial for ambitious young men. Women's responsibility for clothing the household also carried with it a certain amount of socially-expected (though not legally-required) power within the home. Vickery found that one mark of a truly tyrannical husband in the Georgian period was his keeping the key to the linen closet or insisting on handling the financial outlay for it. By so doing, he impinged on the widely accepted authority women held in this area.

Embroidery and other forms of fancy needlework were popular past-times among genteel Georgian women. Craftwork was sometimes criticized by contemporaries such as Hannah More and Mary Wollstonecroft as being nonproductive and frivolous. However, there was an equally strong current of thought that respected and valued decorative needlework. The Reverend James Fordyce praised women for decorating their homes with their own handiwork, seeing it as part of their duty to beautify the home. Others, including author Maria Edgeworth, recognized the value of craftwork in filling the solitary and sedentary hours that many genteel women faced. It could also serve as a distraction and comfort during long family evenings or as a shield when dull or unwelcome visitors came to call.

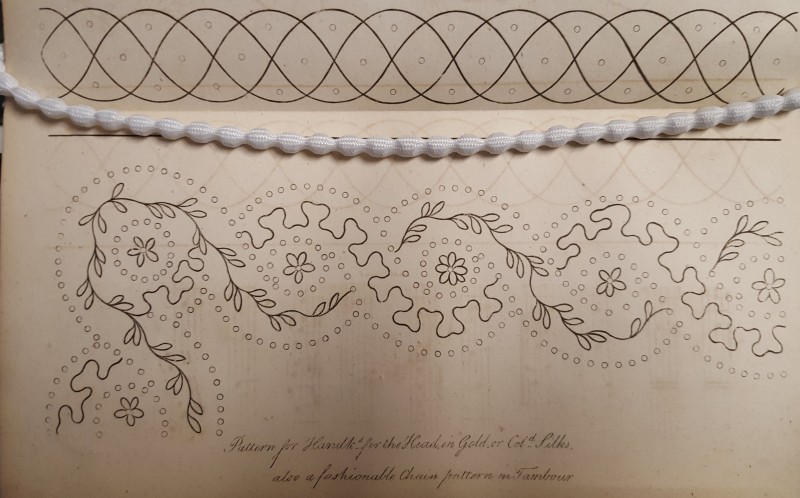

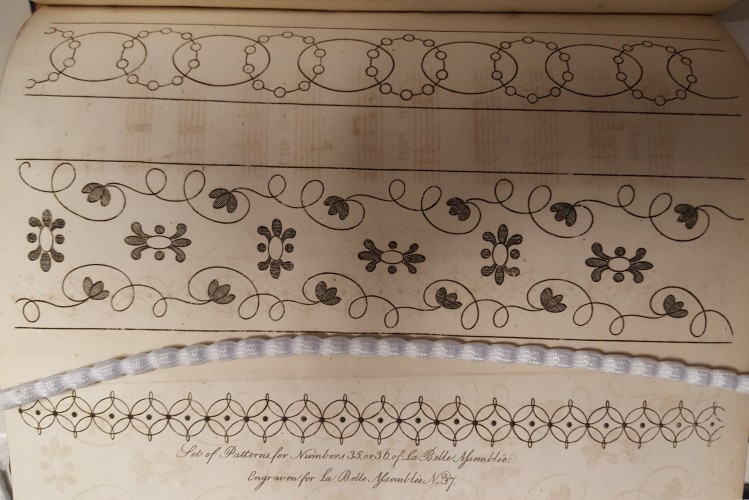

By the early 19th century, working on plain sewing in company was frowned upon, but emboidery continued to be an accepted and much-enjoyed occupation that was suitable almost anywhere. Ladies magazines, such as La Belle Assemblée: Or, Bell's Court and Fashionable Magazine, supplied the demand for new patterns with monthly fold-outs, such pictured below from 1808:

Embroidery Pattern. La Belle Assemblée: Or, Bell's Court and Fashionable Magazine. New Series, Vol. 5. London: J. Bell [etc.], 1808

Embroidery Pattern. La Belle Assemblée: Or, Bell's Court and Fashionable Magazine. New Series, Vol. 5. London: J. Bell [etc.], 1808

Embroidery Pattern. La Belle Assemblée: Or, Bell's Court and Fashionable Magazine. New Series, Vol. 5. London: J. Bell [etc.], 1808

Bibliography

Vickery, Amanda. Behind Closed Doors : At Home in Georgian England. New Haven : Yale University Press, 2009.