Each June, the nonprofit waterway protection and restoration group American Rivers sponsors National Rivers Month to spotlight more than 250,000 rivers and streams throughout the U.S. Visit the American Rivers website to find opportunities to participate in hands-on river clean-up efforts across the country. Approaching the celebration from a literary angle, today's post shares 18th and 19th century descriptions of river journeys. Read on to see America’s rivers through the eyes of John Bartram, Henry David Thoreau, and Mark Twain.

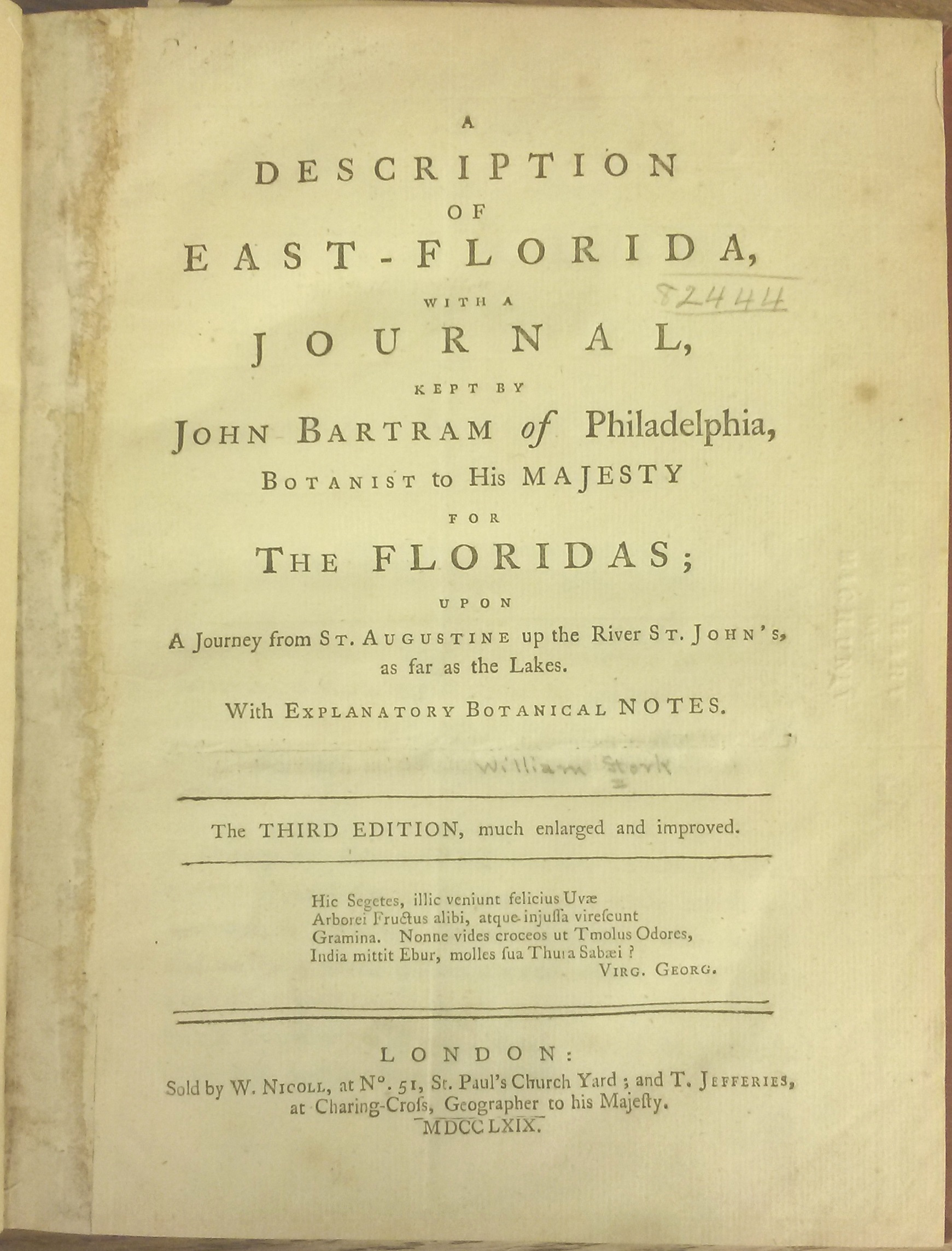

A Description of East-Florida, With a Journal kept by John Bartram of Philadelphia, Botanist to his Majesty for the Floridas; Upon a Journey from St. Augustine up the River St. Johns as Far as the Lakes. With Explanatory Botanical Notes. (1769) 3rd ed. Special Collections F 314 .S885 1769

John Bartram, colonial botanist, Philadelphia farmer, and father of writer William Bartram, traveled extensively throughout the Southeast. One of his last journeys is chronicled in a journal that appeared in partial, edited form in William Stork's A Description of East-Florida: With a Journal Kept by John Bartram of Philadelphia, Botanist to his Majesty for the Floridas; Upon a Journey from St. Augustine up the River St. Johns as Far as the Lakes. With Explanatory Botanical Notes (1769). The longest river in Florida, St. John’s River forms an important part of Florida’s interior wetlands as it moves from its origin in the sawgrass marshes of central Florida into a navigable river moving northeast to the Atlantic Ocean. On January 14th, a little over three weeks into their journey towards St. John's headwaters, Bartram describes the landscape:

Clear morning; wind north. Set out from Coffee-bluff, thermometer 52; a very long reach on the west side of the river, of piney, palmetto-ground, with scrub-oaks; about noon we entered the west lake steering S.W. a ridge of pine-land runs on the east side and a marsh a quarter of a mile more or less between it and the lake, which I think is 8 or 10 miles from north to south, and 5 or 6 miles broad, the marsh is in many places a mile or two wide, and then comes to hammocks of oaks; saw a mullet jump three times in a minute or two, which they generally do before they rest, so are called jumping-mullets; on the south side of this lake is a great low cypress-swamp; here to my great disappointment my thermometer was broke accidentally in striving to take a swarm of bees for their honey, which is practiced both by the whites and Indians, who take great quantitites in the cypress-swamps and pine-lands. We landed on the west side, which was low and rich for 100 yards back, rising gradually from the water to 4 or 5 foot perpendicular, then comes to a level, looking rich and black on the surface for an inch or two, then under it a fine sand to a great depth; this level produceth red-bay, great magnolia, water and live-oaks, liquid amber, hiccory, and some oranges, but no large trees; the lower rich ground produceth gledistia, pishamins, cephalanthus, ash, cypress, and cornu femina: Our hunter killed a large he-bear supposed to weigh 400 pounds, was 7 foot long, cut 4 inches thick of fat on the side, its fore-paw 5 inches broad... (18)

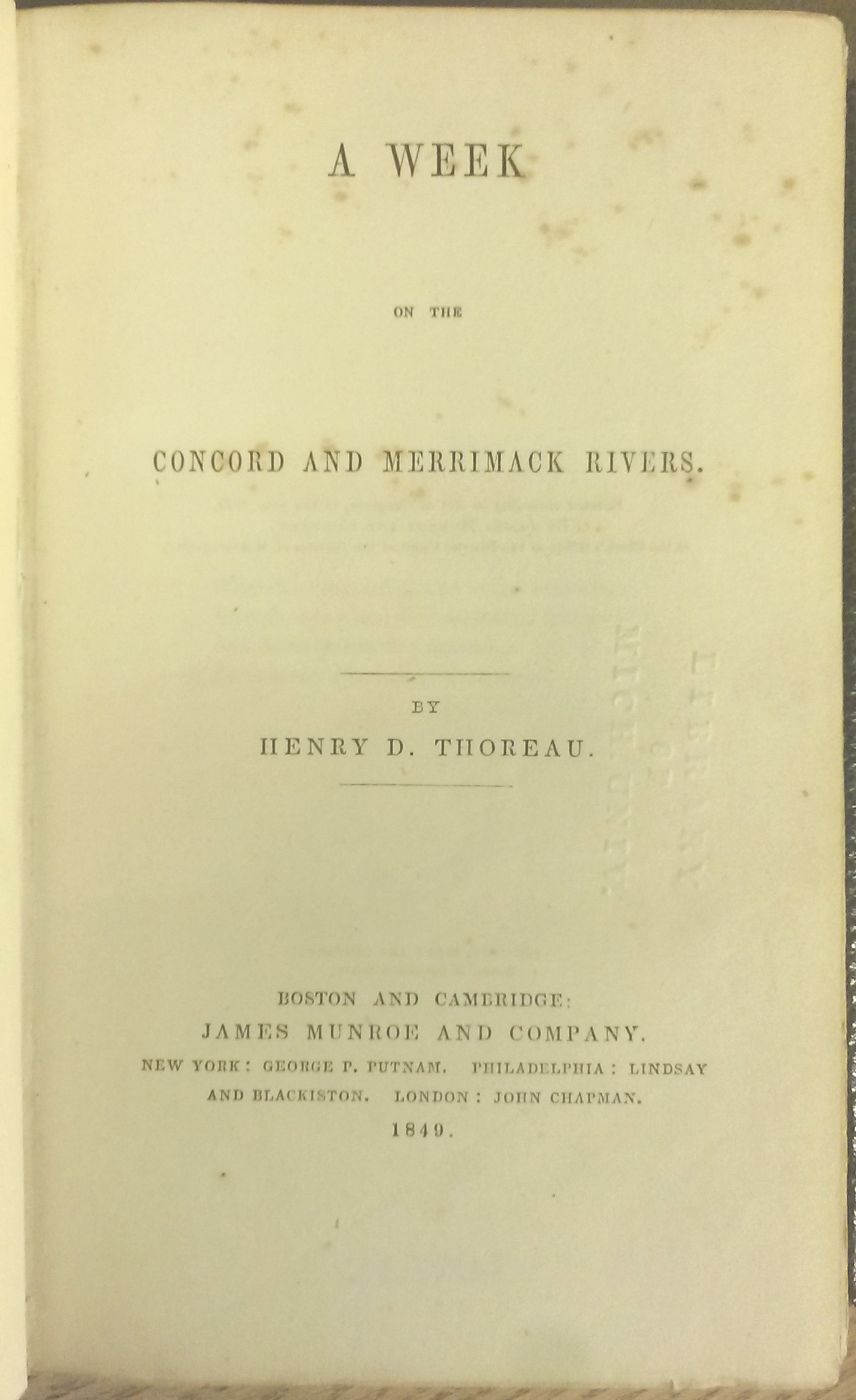

A Week on the Concord and Merrimack Rivers (1849) by Henry David Thoreau. Special Collections F 72 .C5 T5 1849

Transcendentalist philosopher Henry David Thoreau is best-remembered as the author of Walden; or, Life in the Woods (1854), but in an earlier work, he turned his pen to describing running water rather than still ponds. In A Week on the Concord and Merrimack Rivers(1849), Thoreau uses the framework of an 1839 river voyage with his brother John to meditate on “cycles of launch and return, ebb and flow, spring flood and autumn chill,”1 meandering through thoughts on the Revolutionary War, to fish species and the Billerica dam, to the nature of friendship. As the brothers prepare to launch, Thoreau celebrates the central role of rivers in human societies past and present:

The Mississippi, the Ganges, and the Nile, those journeying atoms from the Rocky Mountains, the Himmaleh, and Mountains of the Moon, have a kind of personal importance in the annals of the world. The heavens are not yet drained over their sources, but the Mountains of the Moon still send their annual tribute to the Pasha without fail, as they did to the Pharaohs, though he must collect the rest of his revenue at the point of the sword. Rivers must have been the guides which conducted the footsteps of the first travellers. They are the constant lure, when they flow by our doors, to distant enterprise and adventure, and, by a natural impulse, the dwellers on their banks will at length accompany their currents to the low-lands of the globe, or explore at their invitation the interior of continents. They are the natural highways of all nations, not only levelling the ground, and removing obstacles from the path of the traveller, quenching his thirst, and bearing him on their bosoms, but conducting him through the most interesting scenery, the most populous portions of the globe, and where the animal and vegetable kingdoms attain their greatest perfection.

I had often stood on the banks of the Concord, watching the lapse of the current, an emblem of all progress, following the same law with the system, with time, and all that is made; the weeds at the bottom gently bending down the stream, shaken by the watery wind, still planted where their seeds had sunk, but ere long to die and go down likewise; the shining pebbles, not yet anxious to better their condition, the chips and weeds, and occasional logs and stems of trees, that floated past, fulfilling their fate, were objects of singular interest to me, and at last I resolved to launch myself on its bosom, and float whither it would bear me. (13-14)

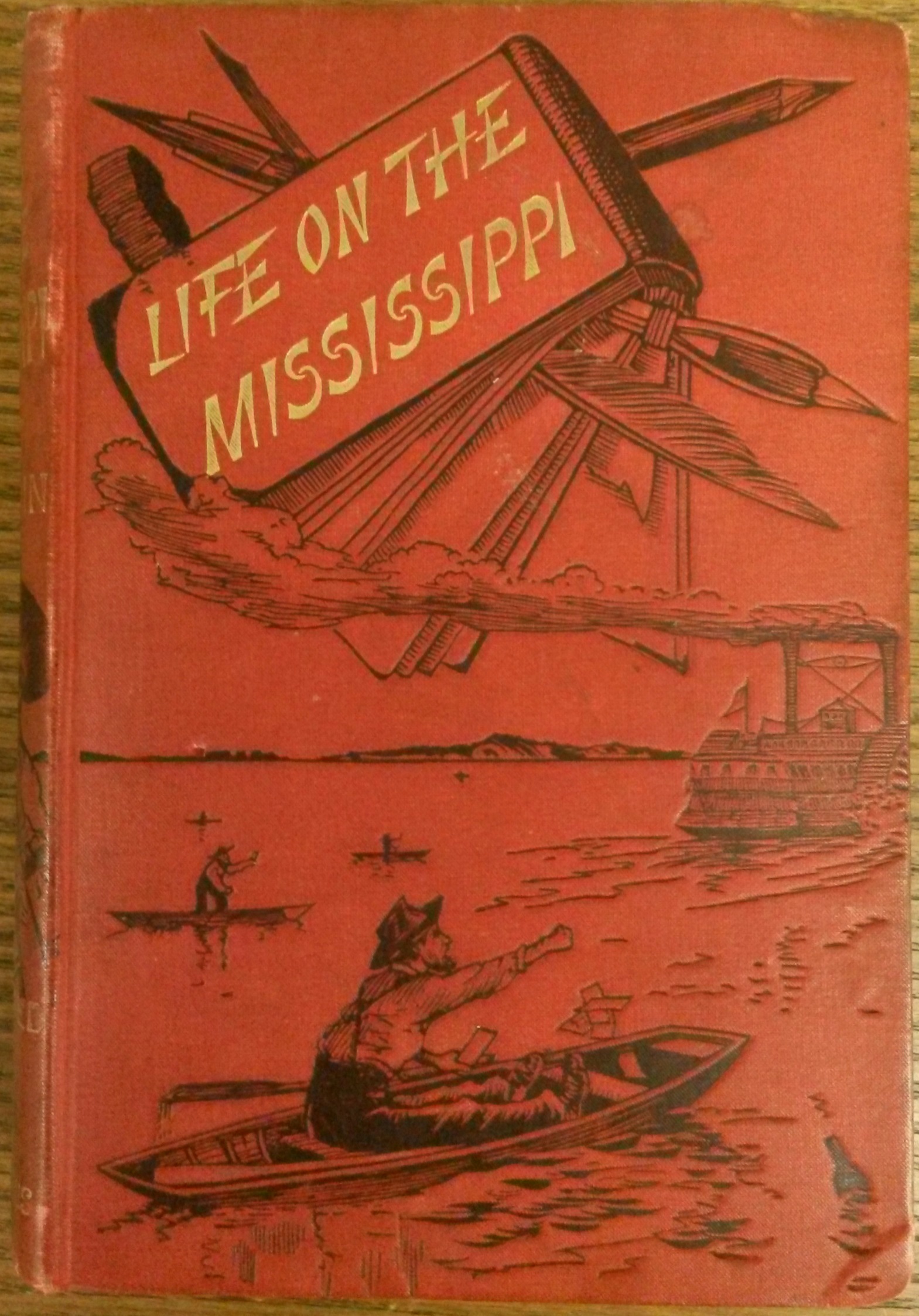

Life on the Mississippi (1883) by Mark Twain.

Special Collections PS1314

In Life on the Mississippi, the quintessentially American author Mark Twain celebrates that most American of American Rivers. In this work, Twain combines his memoir of learning his early trade as a steamboat pilot before the Civil War with a travelogue of journeying up the river’s length many years later. Twain intersperses his lyrical description of the Missisippi’s natural beauties with ironic observations on the changing American economy, as in this passage describing the upper river:

We noticed that above Dubuque the water of the Mississippi was olive-green -- rich and beautiful and semi-transparent, with the sun on it. Of course, the water was nowhere as clear or of as fine a complexion as it is in some other seasons of the year; for now it was at flood stage, and therefore dimmed and blurred by the mud manufactured from caving banks.

The majestic bluffs that overlook the river, along through this region, charm one with the grace and variety of their forms, and the soft beauty of their adornment. The steep, verdant slope, whose base is at the water’s edge, is topped by a lofty rampart of broken, turreted rocks, which are exquisitely rich and mellow in color -- mainly dark browns and dull greens, but splashed with other tints. And then you have the shining river, winding here and there and yonder, its sweep interrupted at intervals by clusters of wooded islands threaded by silver channels; and you have glimpses of distant villages, asleep upon capes; and of stealthy rafts slipping along in the shade of the forest walls; and of white steamers vanishing around remote points. And it is all as tranquil and reposeful as dreamland, and has nothing this-worldly abou tit --nothing to hang a fret or a worry upon.

Until the unholy train comes tearing along -- which it presently does, ripping the sacred solitude to rags and tatters with its devil’s war-whoop and the roar and thunder of its rushing wheels -- and straightway you are back in this world, and with one of its frets ready to hand for your entertainment; for you remember that this is the very road whose stock always goes down after you buy it, and always goes up again as soon as you sell it. It makes me shudder to this day, to remember that I once came near not to getting rid of my stock at all. It must be an awful thing to have a railroad left on your hands.