This post is by Remy Djavaherian (BA in Middle East Studies / Persian Visual Culture, University of Michigan, 2025), drawn from his work with an album from the Islamic Manuscripts Collection. Remy first encountered the album during an independent study with Christiane Gruber in winter 2024. He then worked with the piece in detail as part of his course project for the Islamic Books Arts seminar offered in fall 2024, preparing a transcription and translation for the album's calligraphies and a seminar paper --- Evyn Kropf, curator

In the University of Michigan Library’s Special Collections Research Center, a 19th-century Persian album sits, unassuming. Opening its cover reveals its distinguishing feature: it is made entirely without ink, using only a white page and the light it reflects.

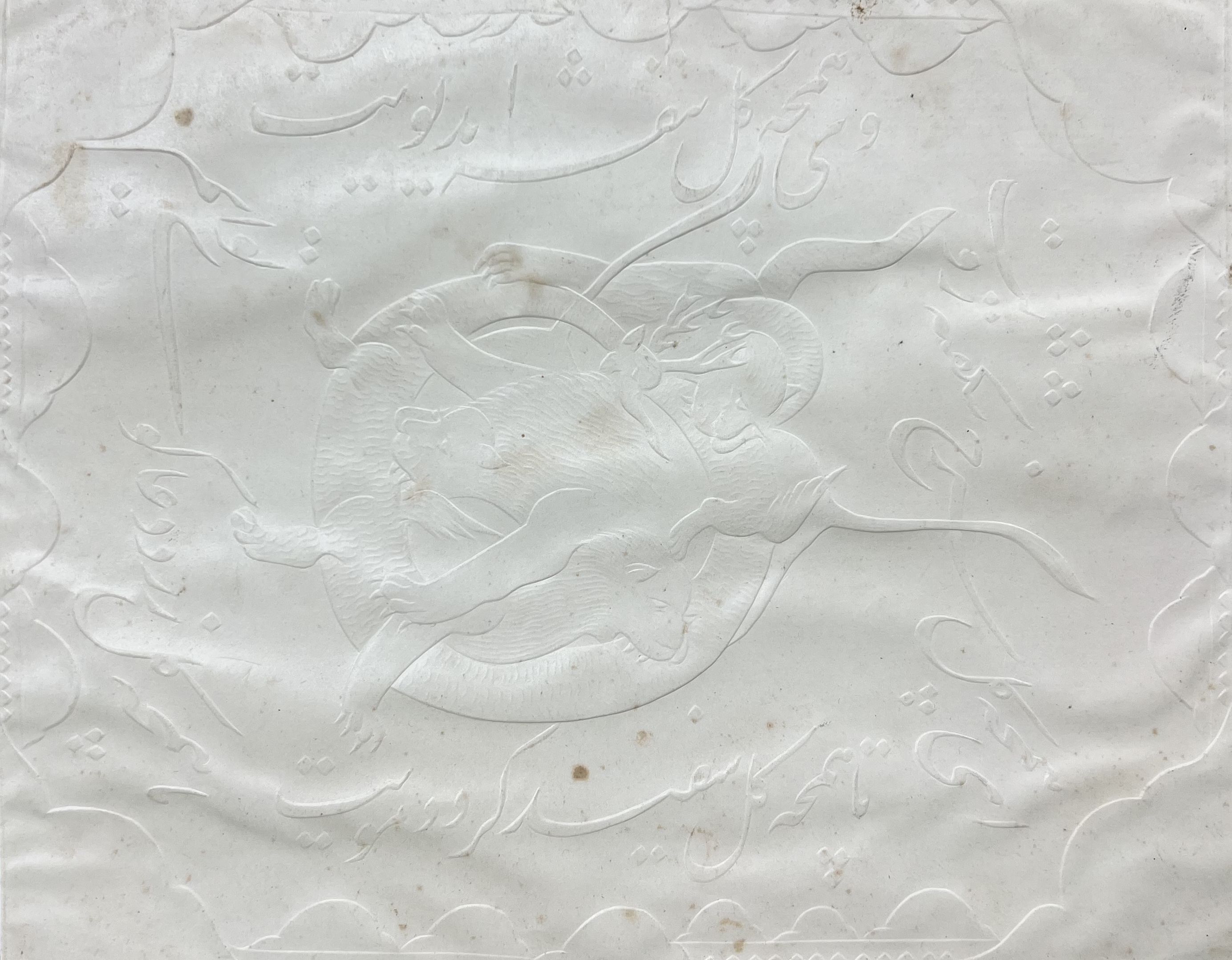

Three lions and a dragon in combat, surrounded by lines of Persian poetry* and a scalloped border (Fol. 7a in Isl. Ms. 279, 1281 H = 1864 or 5 CE)

This is khaṭṭ-i nākhunī (خط ناخنی) or "fingernail calligraphy" -- created entirely by pressing fingernails down on a white sheet of paper. Known in Persian as nakhuni, “of the fingernail,” this artistic technique was popular in Iran from the 17th to 19th centuries. Originating in Iran, nakhuni spread to modern-day Afghanistan, Türkiye, and the Indian subcontinent. It tapered out by the early 20th century, though a few Iranian artists still practice it today. [1] Although tools like metal styluses, molds, and stamps were used to emboss the page, [2] the fingernail was the most prevalent tool. The production process is as follows: a piece of paper is held steady while a sharpened thumbnail carves crisp, colorless creases, braced by another fingernail from behind the paper. When held at the right angle, a seemingly blank canvas becomes flush with life. The delicate maneuvering of these folios allows light and shadow to dance along the page, emphasizing and de-emphasizing letters, phrases, and even entire lines.

Opening page of the album Isl. Ms. 279 (fol. 1a) with Persian verses in praise of Fuad Paşa

The University of Michigan’s album is unique. An inscription within the piece suggests that it may have been produced for the Ottoman statesman Mehmed Fuad Paşa (1814-1869). [3] However, Ottoman-Qajar cross-cultural themes and diplomatic practices raise questions about its origins and meanings. The Persian poetry within the album blends lines from Anwari, [4] Zahir Faryabi, [5] and other poets --- perhaps even Fuad Paşa himself. [6] As a long-standing foreign minister, poet, and a man of modernity, it seems plausible that his original works could have come to the attention of other statesmen.

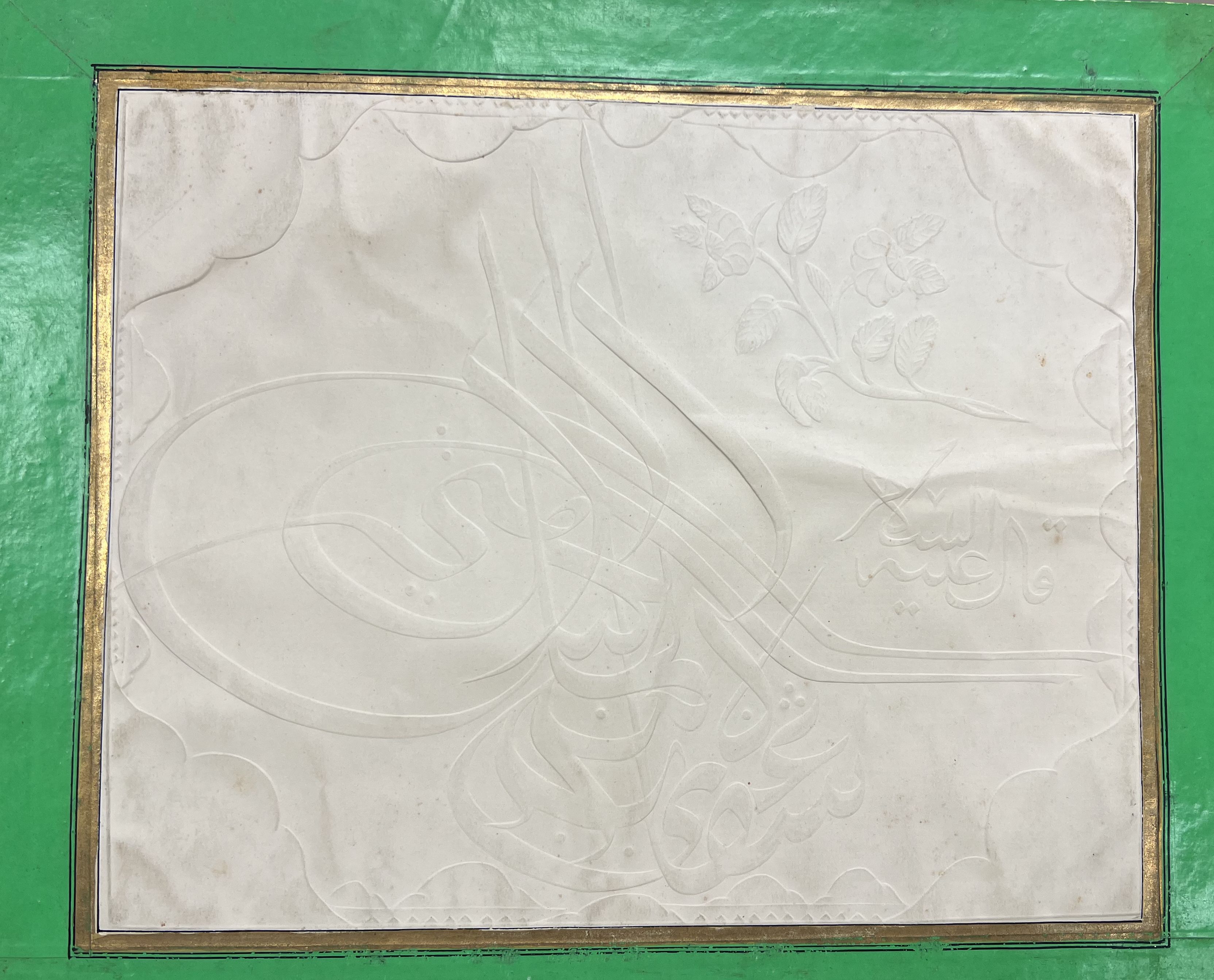

Notably, an Ottoman tuğra (royal signature or insignia) [7] is included, but modified --- a Hadith of Intercession appears in place of the expected name of the sultan. Additionally, Shi’i references like the Garden of Fatima align more closely with Qajar Iran’s religious identity rather than a Sunni Ottoman context. These elements all suggest that the album was crafted in Qajar territory, perhaps as a diplomatic gift for Fuad Paşa.

“Tughra (Insignia) of Sultan Süleiman the Magnificent (r. 1520–66).” (Istanbul, ca. 1555–60) The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Accession no. 38.149.1 (available online open access)

Panel with a full page tuğra bearing a Hadith of Intercession rather than the name of an Ottoman sultan (Isl. Ms. 279, fol. 1b)

Gifts in Qajar-Ottoman relations were rarely neutral; instead, they operated within a gift economy that, per Marcel Mauss, creates obligations between giver and receiver. [8] Incorporating Fuad Paşa's poetry may have been a statement of Qajar diplomacy and cultivation. Alternatively, it may have been requested by the Ottoman statesman himself. What is nevertheless clear, is that his poetry's inclusion in a Qajar album of fingernail art reveals an encounter between Qajar and Ottoman cultural and artistic spheres. The tuğra’s modification could signal Qajar defiance, reimagining an Ottoman imperial symbol to assert Persian authority, or else it may have functioned as a subtle challenge to the Ottoman sultan on the part of Fuad Paşa. In other words, this album embodies the “burden” of reciprocity, which includes a demand for acknowledgment.

Analyzing the album through artistic, cultural, and political lenses reveals a complex narrative transcending its minimalist medium. Its nakhuni technique showcases cultural sophistication, while its diplomatic role highlights Qajar-Ottoman power dynamics, thus offering a holistic framework for better understanding this enigmatic album.

*For complete transcription and translation of the album's calligraphies, see Remy Djavaherian, Isl. Ms. 279, Transcription with translations, https://hdl.handle.net/2027.42/201230

[1] For further reading, see Shiva Mihan’s two-part article on this art, including an introduction to a contemporary nakhuni practitioner cf. Shiva Mihan, "Fingernail art (I): three-dimensional calligraphy and drawing in the 19th century," The Digital Orientalist,11 December 2020 (available online) and "Fingernail art (II): three-dimensional calligraphy and drawing in the 19th century," The Digital Orientalist, 15 February 2021 (available online)

[2] Additionally nakhuni and its relation to low relief Qajar carvings are discussed by Christiane Gruber in her piece "Without pen, without ink: fingernail art in the Qajar period," In Revealing the unseen: new perspectives on Qajar art, edited by Gwenaëlle Fellinger and Carol Guillaume (London: Ginkgo, 2021): 94–105.

[3] See R.H. Davison, "Fuʾād Pas̲h̲a," In Encyclopaedia of Islam New Edition (EI2), edited by Peri Bearman et al (Leiden: Brill, 2012) doi.org/10.1163/1573-3912_islam_SIM_2395

[4] For more on this Iranian poet see Johannes Thomas Pieter de Bruijn, "ANWARI," Encyclopaedia Iranica, published 15 December 1986 (available online open access)

[5] See Johannes Thomas Pieter de Bruijn, "FĀRYĀBĪ, ẒAHĪR-AL-DĪN ABU’L-FAŻL ṬĀHER." Encyclopaedia Iranica, published 15 December 1999 (available online open access)

[6] The son of a famous poet, he was also known to compose his own ghazals, quatrains, and extemporaneous verses. See p.205 in Orhan F. Köprülü, "FUAD PASHA, Keçecizâde," TDV İslâm Ansiklopedisi 13 (1996): 203-205 (available online open access)

[7] For more on the format of the tuğra, see Maryam Ekhtiar, How to Read Islamic Calligraphy, (New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2018), p.48-49

[8] See Marcel Mauss, M. The gift: forms and functions of exchange in archaic societies, translated by Ian Cunnison. New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 1967. For more on gifts of exchange see the essays in Gifts of the sultan : the arts of giving at the Islamic courts, edited by Linda Komaroff. Los Angeles: Los Angeles County Museum of Art ; New Haven : Yale University Press, 2011.

To cite: Djavaherian, Remy. "Invisible gifts, strings attached: an investigation into a Qajar fingernail album." Beyond the Reading Room (The University of Michigan Library), published 23 January 2026 (available online open access)