We are pleased to report about our recent acquisition of the first edition of Alessandro Vellutello’s influential commentary on Dante Alighieri’s Divine Comedy, which was published by Francesco Marcolini da Forlì in Venice in 1544. Undeniably, this edition marked a significant shift in the history of the iconography and reception of Dante’s poem, departing from the previous allegorical interpretations by Cristoforo Landino and Girolamo Benivieni, and challenging Antonio Manetti’s reconstruction of the topography of Hell as described by Dante.

Woodcut and text from La comedia di Dante Aligieri con la nova espositione di Alessandro Vellutello(Venice: Francesco Marcolini da Forlì, 1544)

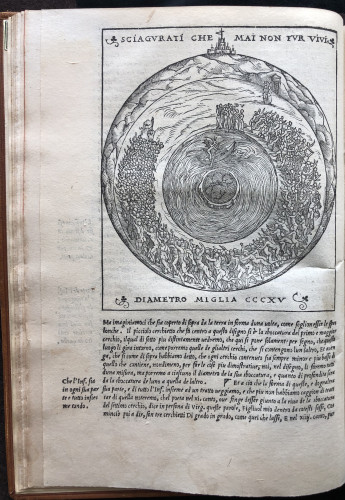

Richly illustrated with 87 woodcuts, three of which are full-page illustrations introducing each of the three parts (Inferno, Purgatorio, and Paradiso), Vellutello’s edition proposed a new way to interpret, and visualize, Dante’s poem. While previous illustrations of the Commedia were mostly tools to aid readers to identify major events within the poem, it seems clear that Vellutello sought to challenge his audience by pairing the intellectualism of his commentaries with the artistry of these woodcuts. This synergy between text and image is clearly manifested through the illustrated commentaries on the Inferno. In fact, the book opens with an introduction called Descrizzione de lo Inferno, in which ten highly artistic woodcuts closely follow Vellutello’s interpretation of how Dante conceived the geography of Hell. For instance, to introduce, and prepare, the reader to the oneiric experience of the journey through the various levels, or circles, of the Inferno, Vellutello first painstakingly describes its exact location and size. He suggests drawing an imaginary straight line beginning from the bowels of earth, just above its center, and going upward toward a location below Mount Sion, the site of Jerusalem. There, we would see the large mouth of a pit of equal width and depth: 3000 braccia. However, how do we figure out the length of a braccio? Vellutello explains that each braccio is six times the length of the vertical line conveniently drawn on the margin of the page: “intendendo che ogni braccio sia a punto sei volte la lunghezza de la linea posta qui di fuori in margine…”

The line to measure Hell, from La comedia di Dante Aligieri con la nova espositione di Alessandro Vellutello (Venice: Francesco Marcolini da Forlì, 1544)

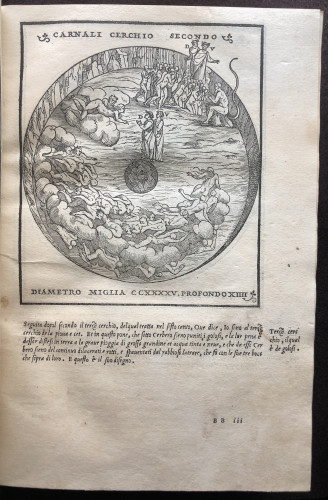

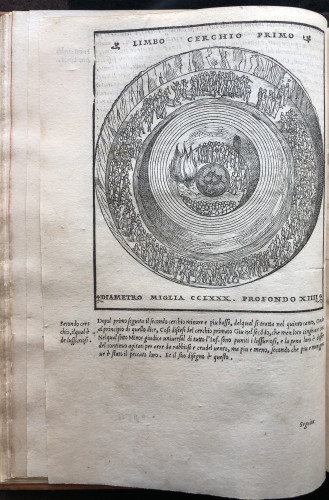

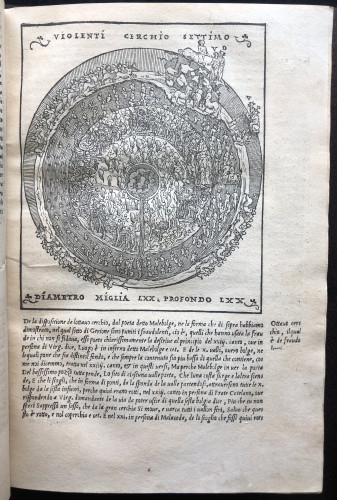

As the reader travels downward, the measurement of each circle gradually decreases, offering us an overall image of the Inferno in the shape of a funnel. In addition, most of the woodcuts describing the successive circles of Hell includes the figures for their respective width (diametro) and depth (profondità).

Woodcut and text from La comedia di Dante Aligieri con la nova espositione di Alessandro Vellutello (Venice: Francesco Marcolini da Forlì, 1544)

Woodcut and text from La comedia di Dante Aligieri con la nova espositione di Alessandro Vellutello (Venice: Francesco Marcolini da Forlì, 1544)

Woodcut and text from La comedia di Dante Aligieri con la nova espositione di Alessandro Vellutello (Venice: Francesco Marcolini da Forlì, 1544)

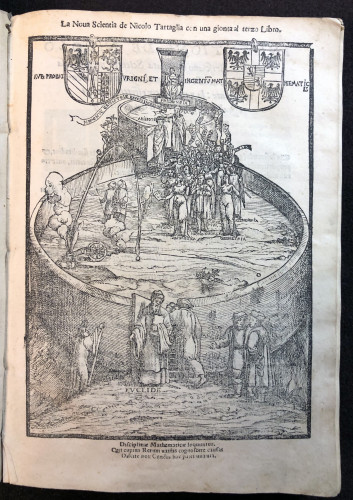

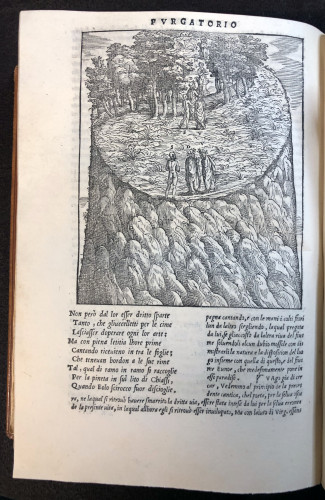

Massimiliano Rossi has suggested that Vellutello himself might have drawn the sketches for the illustrations, commissioning the woodcuts to the German artist Giovanni Britto (Johannes Brit or Breit), who was active in Venice in the first half of the sixteenth century and was connected to Titian’s workshop. This attribution is based on the identification of other woodcuts that share similar aesthetic features and are signed with the artist’s initial, like the frontispiece, Il colloquio tra Petrarcha e Girolamo Malipiero, in Girolamo Malipiero’s Il Petrarcha Spirituale (Venice: Francesco Marcolini, 1536). Furthermore, argues Rossi, we can probably trace Britto’s artistic style in the allegorical frontispiece he did for Nicolò Tartaglia’s Nova Scientia (Venice: Stephano da Sabio, 1537). Its frontispiece depicts the accession of mathematicians to reach the throne of Philosophy and, strikingly, the style and structure of this illustration resurface in the second woodcut of Purgatorio in Vellutello's edition. 1

Frontispiece of a later edition of Nova Scientia that reprints the original 1537 illustration: Nicolò Tartaglia. La nova scientia de Nicolò Tartaglia con una gionta al terzo libro (Venice: Nicolò de Bascarini, 1554)

The second woodcut of Purgatorio, from La comedia di Dante Aligieri con la nova espositione di Alessandro Vellutello (Venice: Francesco Marcolini da Forlì, 1544)

The impact of this richly illustrated and commented edition of the Commedia can be measured, for example, by the fact that the blocks would re-appear in other publications. Francesco Marcolini used again the Inferno blocks for the publication of Antonio Francesco's Doni’s I mondi in 1552-1553. And following the death of Marcolini, the blocks used in the Commedia ended in the hands of the Venetian firm of the Sessa brothers, who re-used them in large folio commentated editions of the Commedia published in 1564, 1578, and 1596. 2

1. Massimiliano Rossi. "Alessandro Vellutello e Giovanni Britto che 'per sé fuoro'. Sul corredo grafico della 'Nova esposizione' (1544)", in Un giardino per le arti: "Francesco Marcolino da Forlì". La vita, l'opera. el catalogo. Ed. Paolo Procaccioli, Paolo Temeroli & Vanni Tesei. Atti del Convegno internazionale di studi Forlì, 11-13 ottobre 2007. Bologna: Editrice Compositori, 2009: 366, 371, 379-380.

2. Ruth Mortimer. Harvard College Library Department of Printing and Graphic Arts. Catalogue of Books and Manuscripts. Part II: Italian 16th Century Books. Vol. 1. Cambridge, MA.: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1974: 207-211.