Although largely forgotten today, The Water-Babies was once one of the most popular Victorian literary fairy tales. Written by Charles Kingsley, chaplain to Queen Victoria, it appeared serially in Macmillan’s Magazine from August 1862 to March 1863 and was published later in 1863 in book form, with two illustrations by Sir Noel Paton. The Water-Babies was an immediate literary success, and several scholars even credit it with a significant role in the passage of an 1864 law banning the use of child chimney sweeps. Leaping from realistic adventure, to fantastical exploration of aquatic biology, to an imaginary voyage in the tradition of Gulliver’s Travels, Kingsley’s The Water-Babies is a remarkably imaginative tour de force.

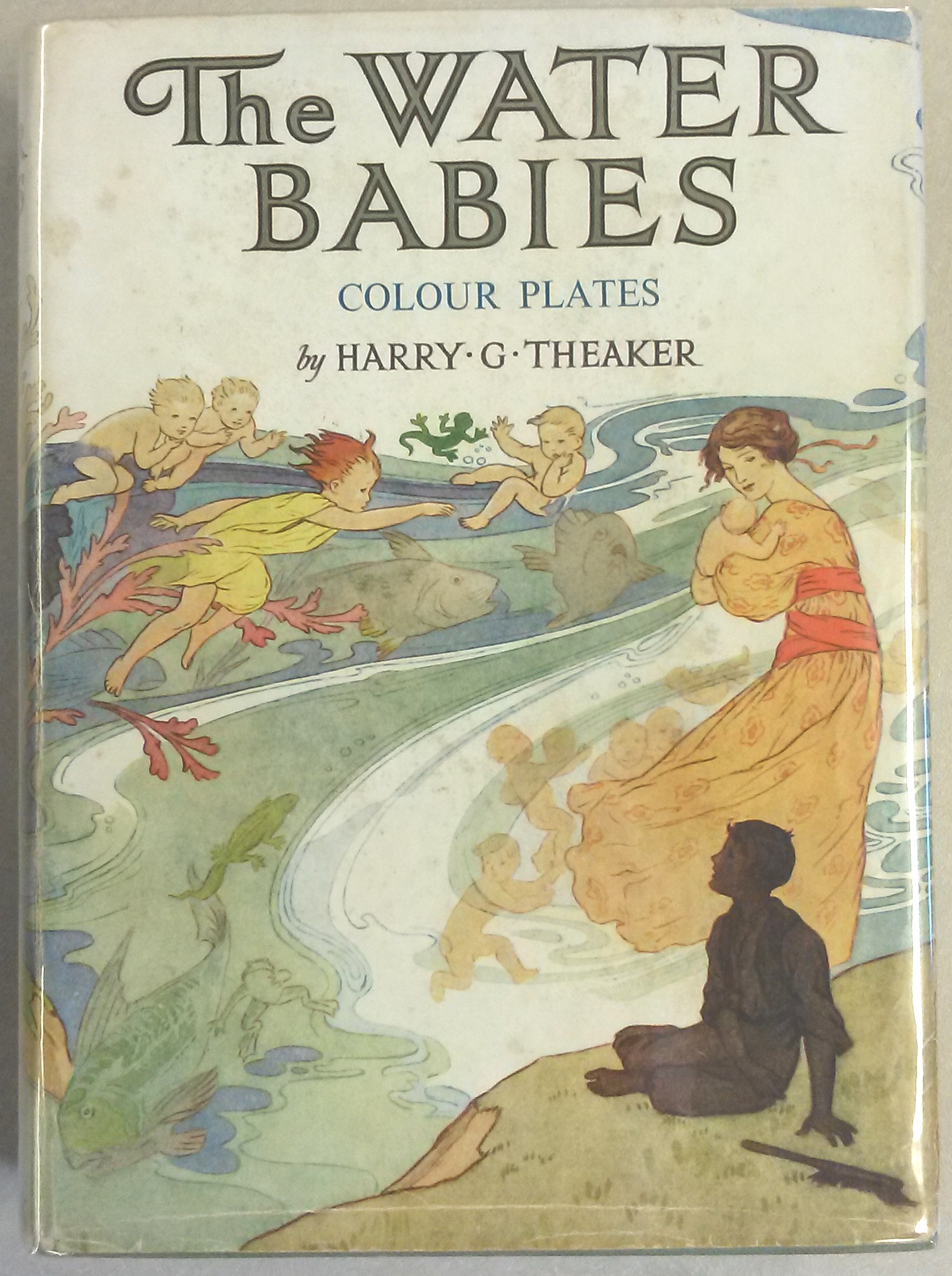

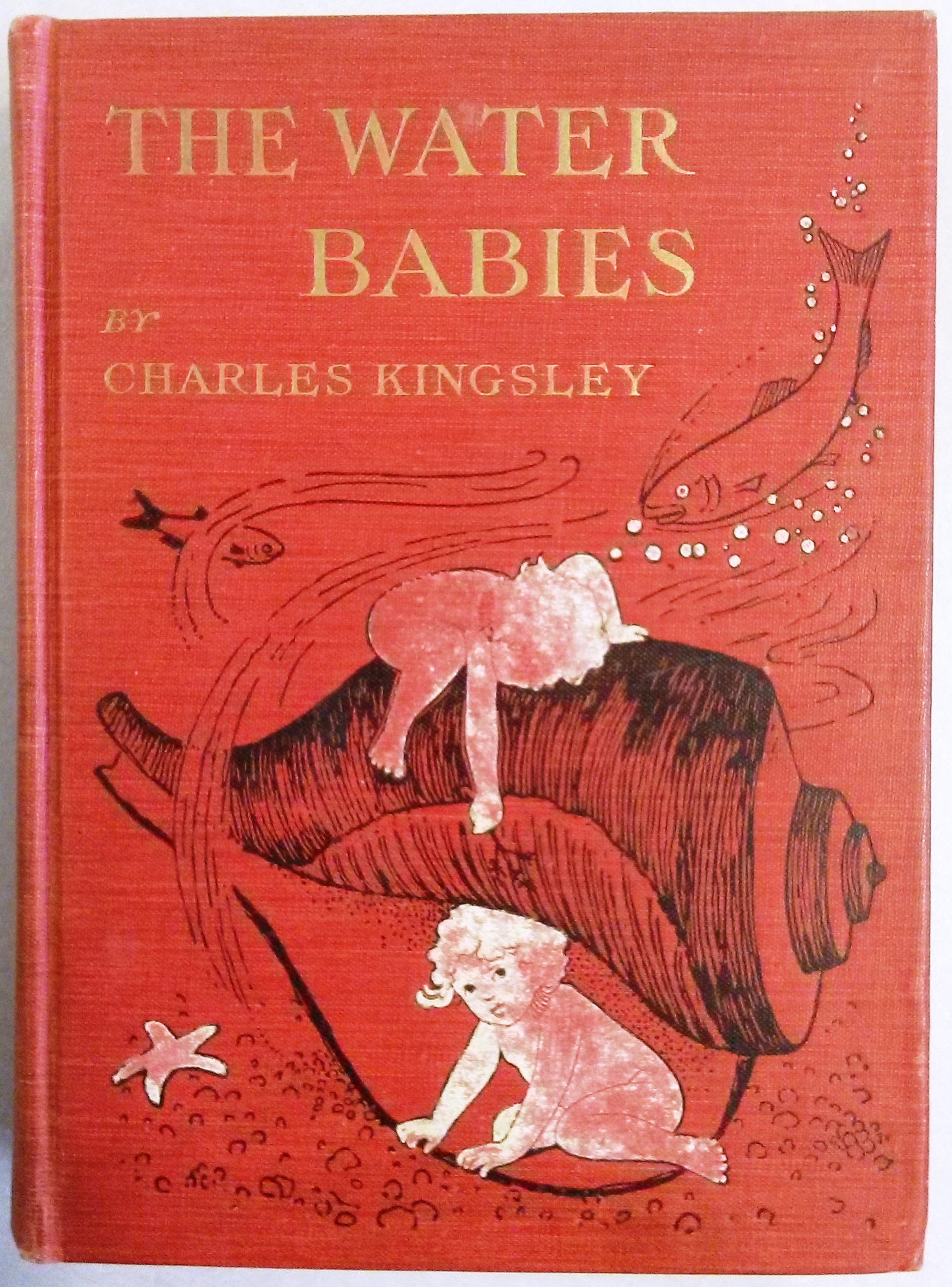

1960s Ward, Locke, and Co. London edition of The Water-Babies by Charles Kingsley. Children's Literature

PR 4842 .W3 1960

It begins with Tom, a plucky, but much-abused chimney sweep accidentally descending the wrong chimney in a great country house where he discovers, by catching sight of himself in a mirror for the first time in his life, just how very dirty he is; and frightens the daughter of the house with his dirt and noise. Running away over the hills in fear and shame, with the whole household chasing after him, Tom becomes delirious and falls asleep in a stream. Discovering his clothes and body the next day, his pursuers believe that he drowned.

However, Tom is very much alive, for the fairies have transformed him into a water-baby, “3.87902 inches long, and having round the parotid region of his fauces a set of external gills...just like those of a sucking eft.” Tom spends the following weeks exploring his new environment and learning (along with the reader) about caddisflies, dragonflies, and trout.

Desiring to see more of the world, Tom sets off down the river to the seacoast, encountering more aquatic life, and inadvertently contributing to the death of the little girl from chapter 1, Ellie, who hits her head as she leaps down the rocks to catch him. Only after Tom helps a lobster to escape from a trap is he able to see his fellow water-babies and accompany them to St. Brandan’s fairy isle, where the fairies Mrs. Bedonebyasyoudid and Mrs. Doasyouwouldbedoneby care for them.

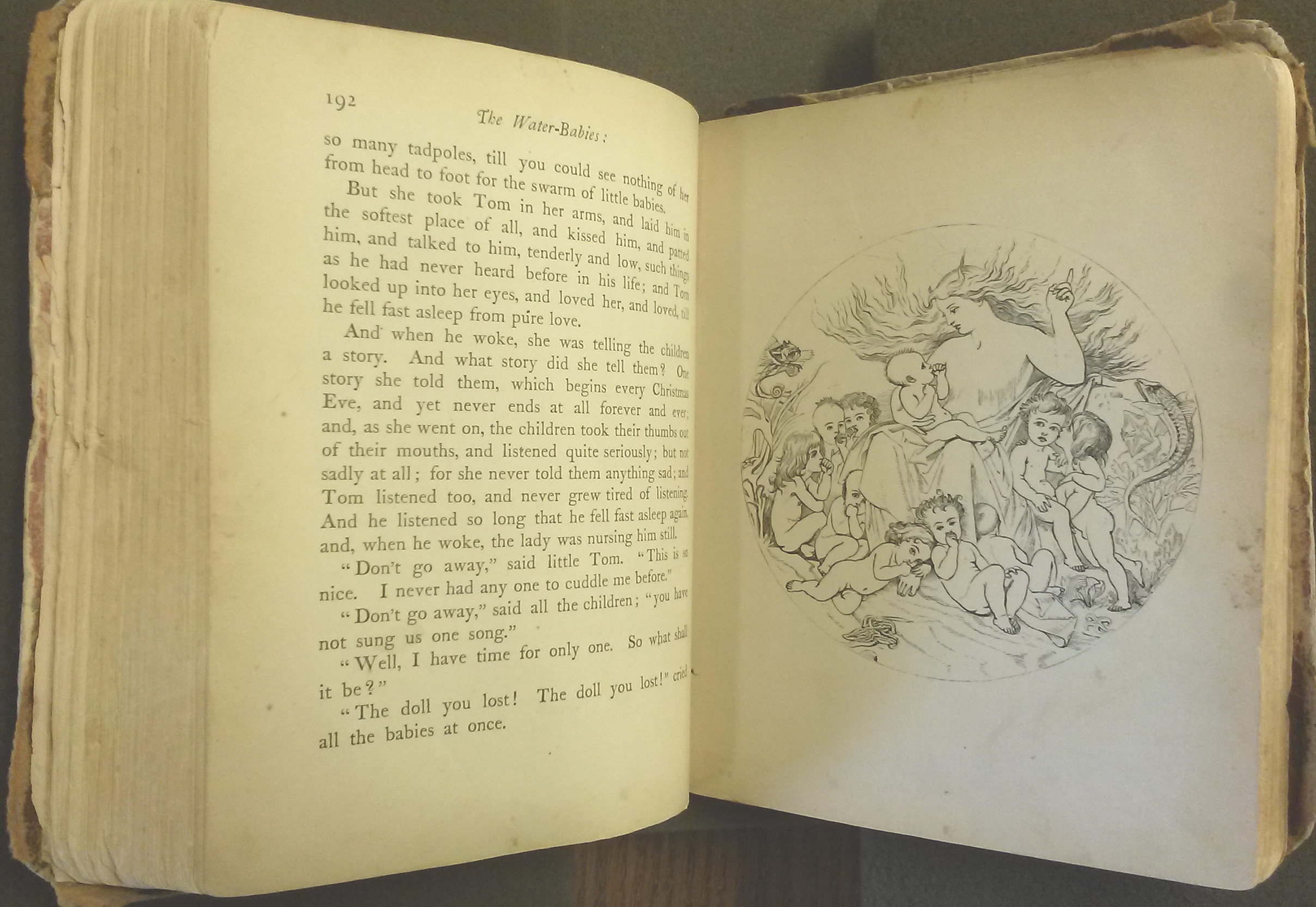

1864 American edition of The Water-Babies by Charles Kingsley. Children's Literature Collection PR 4842 .W3 1864.

Poor Tom, who still has much to learn in his moral education, breaks out in spines after stealing sweets from Mrs. Bedonebyasyoudid and is given a special tutor in the person of Ellie. Tom is anxious to accompany Ellie when she goes home (to heaven) on Sundays, but the fairies tell him, “Little boys who are only fit to play with seabeasts cannot go there...Those who go there must go first where they do not like, and do what they do not like, and help somebody they do not like.”

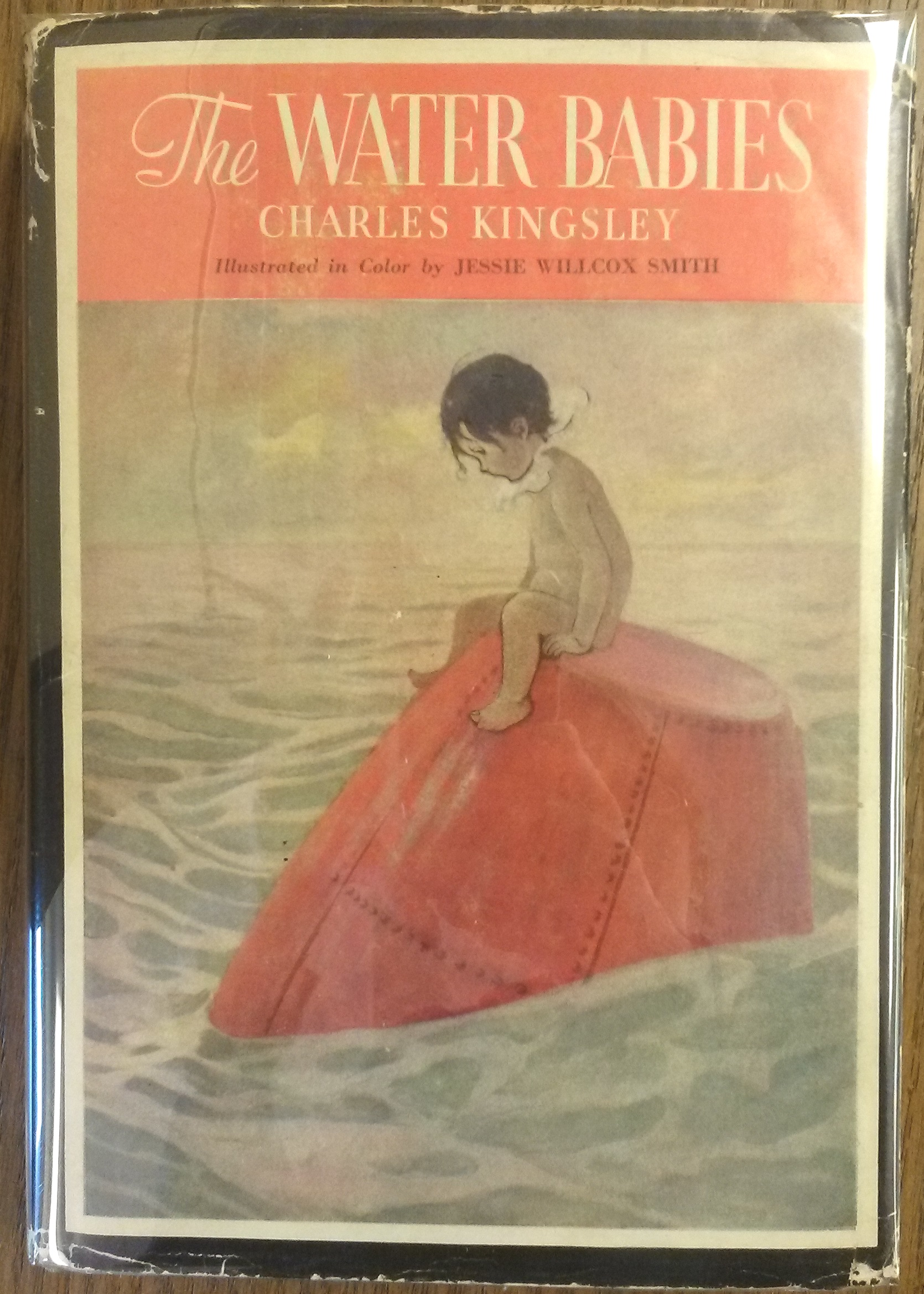

1937 Garden City Publishing, NY edition of The Water-Babies by Charles Kingsley. Children's Literature PR 4842 .W3 1937.

Tom sets off into the world to find his old chimney-sweep master, Mr. Grimes, who is being punished at the Other-end-of-Nowhere. Along the way, he encounters a series of Gulliverian islands, such as Waste-paper-land, “where all the stupid books lie in heaps,” and the Isle of Tomtoddies, where too many lessons have withered the children's limbs and turned them into turnips and radishes who wail “[T]he examiner’s coming!”

At last, Tom reaches the Other-end-of-Nowhere. Touched by Tom’s forgiveness of his ill-treatment, and the news (from Mrs. Bedonebyasyoudo) of his mother’s death, Mr. Grimes repents his wicked ways. Mrs. Bedonebyasyoudid returns Tom to St. Brandon’s Isle and he is now allowed to go home with Ellie on Sundays because “He has won his spurs in the great battle, and become fit to go with you, and be a man; because he has done the thing he did not like.”

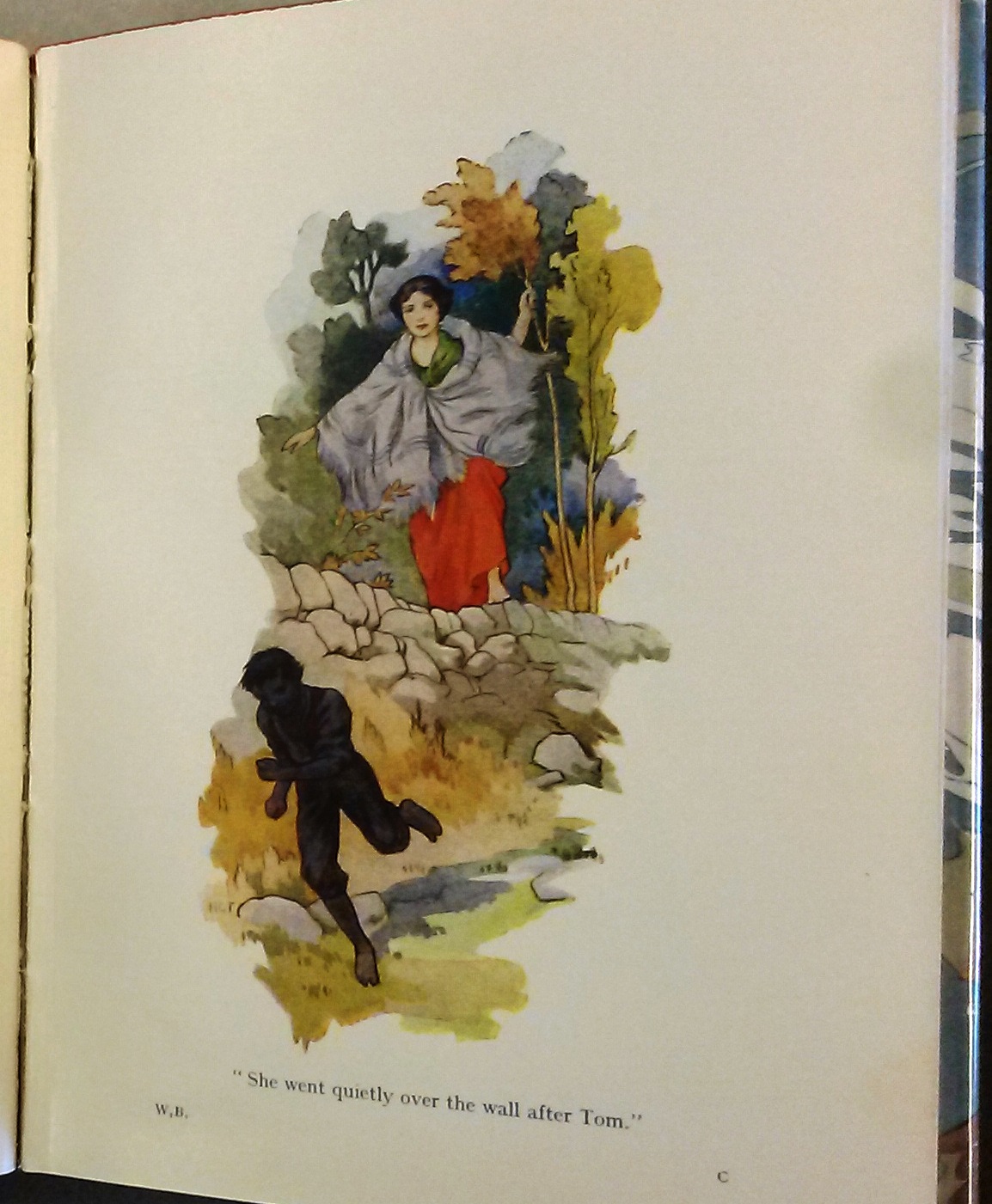

1960s Ward, Locke, and Co. London edition of The Water-Babies by Charles Kingsley.Children's Literature PR 4842 .W3 1960

In writing The Water-Babies, Kingsley sought to write an evangelical parable based in appealing make-believe, without the heavy-handed didacticism that he despised in much of the existing moral literature for children. A naturalist and defender of Darwin’s theory of evolution, he also sought to share the wonders of the natural world through Tom’s aquatic journeys. Unfortunately, along the way, Kingsley peppered his fairy tale with an array of witty tangents no doubt amusing to upper-middle class Victorian England but highly offensive to practically everyone else. As literary scholar Goldthwaite puts it, “So vast is the man’s xenophobia…that his slights against Americans, Papists, Jews, [blacks], and a host of others quickly gather themselves into such a company that it becomes almost pointless to take offense.”[1]

These tangents are likely a large part of the reason that, although scholarly interest remains lively, The Water-Babies no longer forms part of what Deborah Stevenson calls the canon of sentiment. Adults purchase, read, and pass down “the familiar and the beloved,” and favor “books that comfort over books that challenge.”[2] Certainly in its original form - riddled with xenophobia and bigotry - The Water-Babies is an unlikely birthday gift for beloved nieces or nephews, and K-12 teachers are unlikely to single it out for class discussion.

1917 Lippincott edition of The Water-Babies by Charles Kingsley. Children's Literature PR 4842 .W3 1917

When new editions of The Water-Babies have been published in recent decades, they are usually heavily edited and abridged. For example, during Tom’s journey down the rain-swollen river to the ocean, Kingsley writes, “Tom found himself in the middle of a salmon river. And what sort of a river was it?” and then spends three pages describing the failings of the Irish and Welsh (followed by three more pages extolling the virtues of English salmon-management). This passage from the 1917 Lippincott edition illustrates something of his tone:

So you must not trust Dennis, because he is in the habit of giving pleasant answers: but, instead of being angry with him, you must remember that he is a poor Paddy, and knows no better; so you must just burst out laughing; and then he will burst out laughing too, and slave for you, and trot about after you, and show you good sport if he can--for he is an affectionate fellow, and as fond of sport as you are--and if he can’t, tell you fibs instead, a hundred an hour; and wonder all the while why poor ould Ireland does not prosper like England and Scotland, and some other places, where folk have taken up a ridiculous fancy that honesty is the best policy. [3]

1979 Facsimile Classics edition of The Water-Babies by Charles Kingsley. Children's Literature PR 4842 .W3 1979

In contrast, the 1979 Facsimile Classics edition from Mayflower books contracts all six pages into two sentences:

“Tom found himself out in the salmon river. Tom thought nothing about what the river was like.”[4]

Certainly this makes the passage less offensive, but it also turns it into awkward, silted prose. The 1984 Penguin Classics edition manages with more finesse by drawing on one of Kingsley’s extraneous paragraphs extolling the virtues of English wood-engraver Thomas Bewick and his depictions of streams (though removing the actual reference to Bewick):

…Tom found himself out in the salmon stream at Harthover. A full hundred yards broad it was, sliding on from broad pool to broad shallow, and broad shallow to broad pool, over great fields of shingle, under oak and ash coverts, past low cliffs of sandstone, past green meadows, and fair parks, and a great house of grey stone, and brown moors above, and here and there against the sky the smoking chimney of a colliery. But Tom thought nothing about what the river was like.[5]

1984 Puffin Classics edition of The Water-Babies by Charles Kingsley. Children's Literature PR 4842 .W3 1984.

To give an idea of just how much abridgement is deemed necessary to appeal to a modern audience, consider that the original text is 350 pages in length, while the Facsimile Classics edition is 280 pages (in large print), and the Puffin Classics just 192. Abridgements, of course, always raise questions about what is being excised, and to what extent passages can be edited while remaining true to the spirit of the original. At least one scholar suggests that the Puffin edition (which claims only to remove “blatant sermonizing”) also diluted the work's unified aesthetic character and literary appeal.[6]

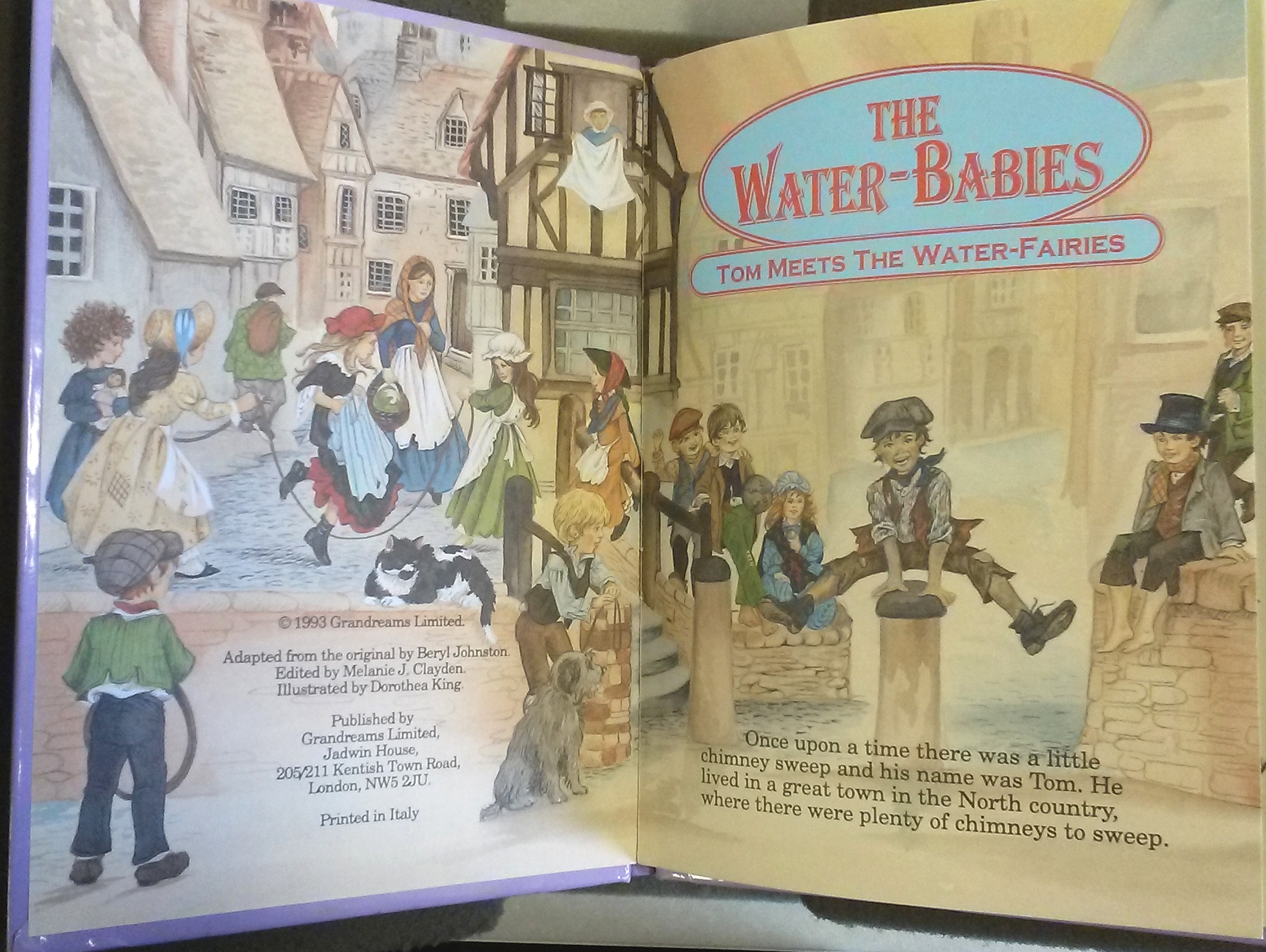

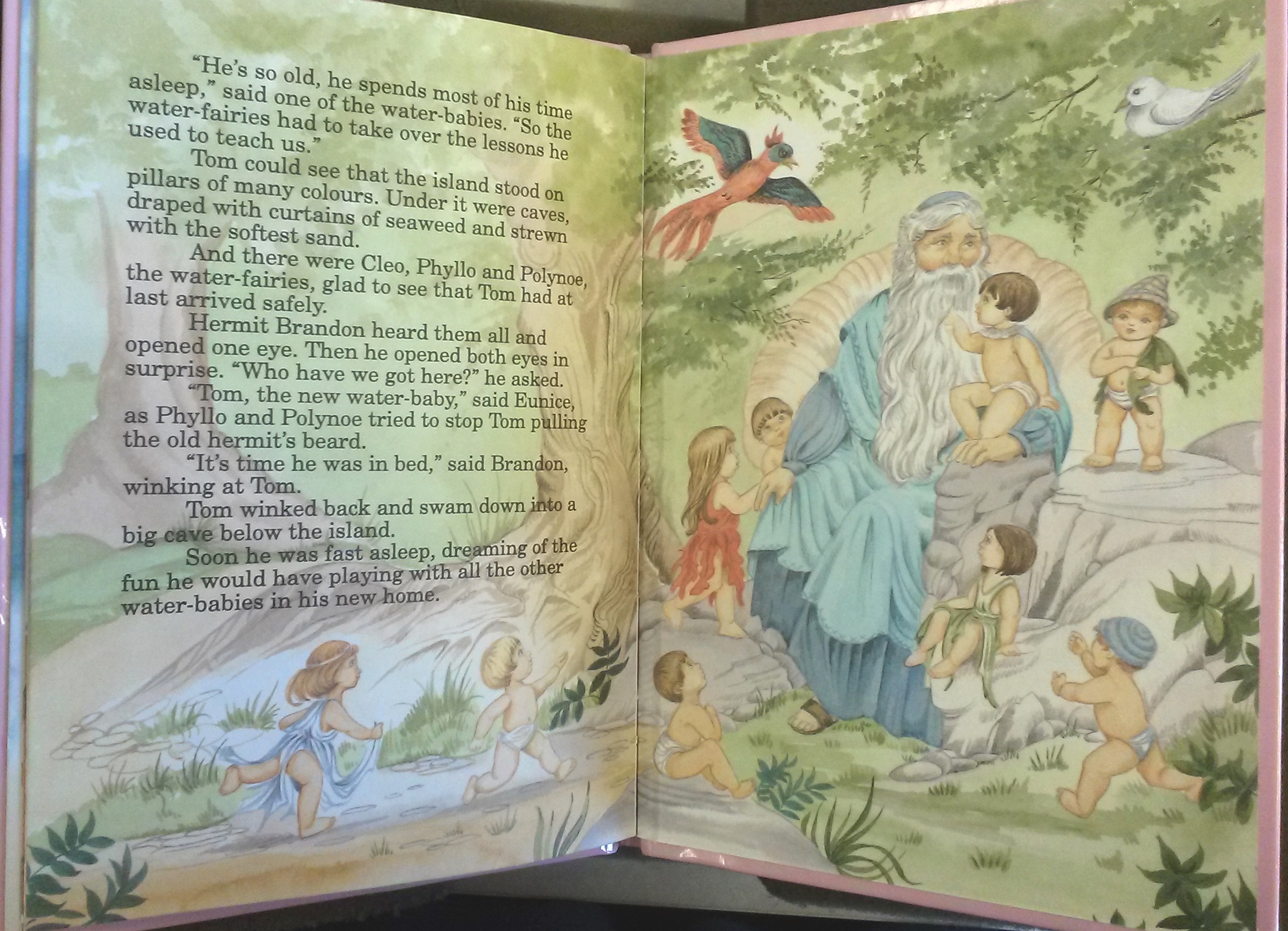

Perhaps the most extreme abridgement is represented by the 1990s Water-Babies picture books from the Good Night, Sleep Tight Storybook series. The first two books (of 20 pages each) depict a ragged, but happy & healthy chimney sweep who appears quite light-hearted even as he runs for his life and finds his way to the lap of a white-bearded patriarch on St. Brandon’s Isle without serious misadventure. While the illustrations of sea creatures and cherubic water babies have a certain appeal, Kingsley’s playful language and his depiction of Tom’s moral growth all but disappear.

The Water-Babies: Tom Meets the Water-Fairies, adapted from the original by Beryl Johnston and illustrated by Dorothea King. A Good Night, Sleep Tight Storybook (1993).

Children's Literature PS 3560 .O3872 W37 1993.

The Water-Babies: Down to the Sea, adapted from the original by Beryl Johnston and illustrated by Dorothea King. A Good Night, Sleep Tight Storybook (1993). Children's Literature

PS 3560 .O3872 W365 1993

[1] John Goldthwaite, Natural History of Make-Believe: A Guide to the Principal Works of Britain, Europe, and America (Cary, NC, USA: Oxford University Press, USA, 1996): 72.

[2] Deborah Stevenson, "Sentiment and Significance: The Impossibility of Recovery in the Children's Literature Canon or, The Drowining of The Water-Babies," The Lion and the Unicorn 21, no. 1 (1997): 115.

[3] Charles Kingsley, The Water Babies (Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott, 1917): 112.

[4] Charles Kingsley, The Water Babies (New York: Mayflower Books, 1979): 105.

[5] Charles Kingsley, The Water Babies (Harmondsworth: Puffin Books, 1984): 71-72.

[6] Jonathan Padley, "Marginal(ized) Demarcator: (Mis)Reading The Water-Babies," Children's Literature Association Quarterly 34, no. 1 (2009): 51.