In the early 19th century, the Brother Grimms’ collections of German fairy tales popularized the fairy tale genre among Europe’s burgeoning middle classes. Following a generation later, Danish author Hans Christian Andersen rose from obscurity to international fame through his haunting and often tragic fairy tales. Andersen's initial publications were based upon his many childhood hours listening to folk tales told in the spinning room of the asylum where his grandmother worked. However, he soon expanded his repertoire to original inventions, such as “The Little Match Girl,” “The Little Mermaid,” and “The Red Shoes.”

The Special Collections Library holds two illustrated editions of "The Red Shoes," both from the 1920s. The first is a French translation of a selection of Andersen's fairy tales Contes D'Andersen (1920), published in Paris by La Sirène and illustrated by full-page color plates and small black and white vignettes by French illustrator Georges Delaw. The second is a 1928 fine press edition of The Red Shoes, published by British bookseller and radio producer Douglass Cleverdon, and signed by German illustrator Willi Harwerth, who produced the small, hand-colored wood engravings throughout.

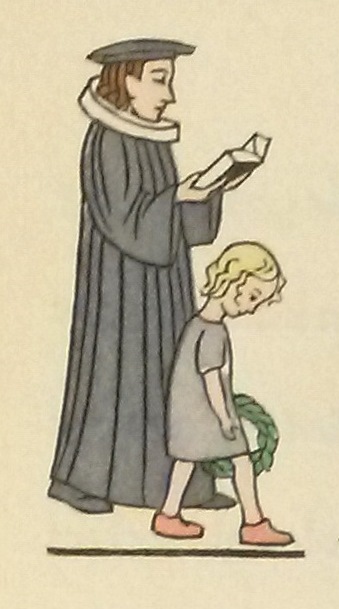

Detail from The Red Shoes,

1928, p. 12.

First published as part of Nye Eventyr. Første Bind. Tredie Samling in 1845, “The Red Shoes” tells the story of an orphan girl whose uncontrolled desire for frivolous pleasures leads to her downfall. Karen's family is so poor that she has to go barefoot in summer and wear rough wooden shoes all winter. Just when Karen’s mother dies, Karen receives a gift of clumsily-made red cloth shoes from an old shoemaker’s wife. She wears these red shoes to her mother's funeral, even though “they were certainly not suitable for mourning.” A wealthy widow passing by decides to adopt Karen, but burns the “hideous” red cloth shoes.

Years later, Karen sees a princess dressed all in white except for her beautiful red morocco shoes. When it comes time for Karen to have new clothes for her confirmation, she tricks her nearly-blind benefactress into purchasing red patent leather shoes. Upon discovering the deception, the widow tells Karen she must never wear anything but black shoes to church. The next Sunday, however, Karen is again unable to resist the red shoes. At the church door, an old crippled soldier makes a cryptic comment that later turns out to be a curse, “Dear me, what pretty dancing-shoes!...Sit fast, when you dance.” Later on, as everyone exits the church, the soldier says again, “Dear me, what pretty dancing shoes!” and Karen suddenly finds herself dancing around the churchyard.

Soon afterwards, the old widow falls ill. Disappointed in her plans to go to a grand ball, Karen looks at the beautiful red shoes, thinking ‘there was no sin in doing that” and then puts the shoes on, thinking “no harm in that either,” but then she takes one final step and leaves her dying benefactress to go dancing. The shoes take control at the ball and force Karen to dance not only through the night, but for days and weeks all across the countryside. A stern angel watching from the church door warns her that she will “dance in your red shoes till you are pale and cold, till your skin shrivels up and you are a skeleton.” Karen begs for mercy, but her shoes carry her away before she hears the angel’s response, and she continues to dance, even as she watches her adopted mother’s coffin carried from their home.

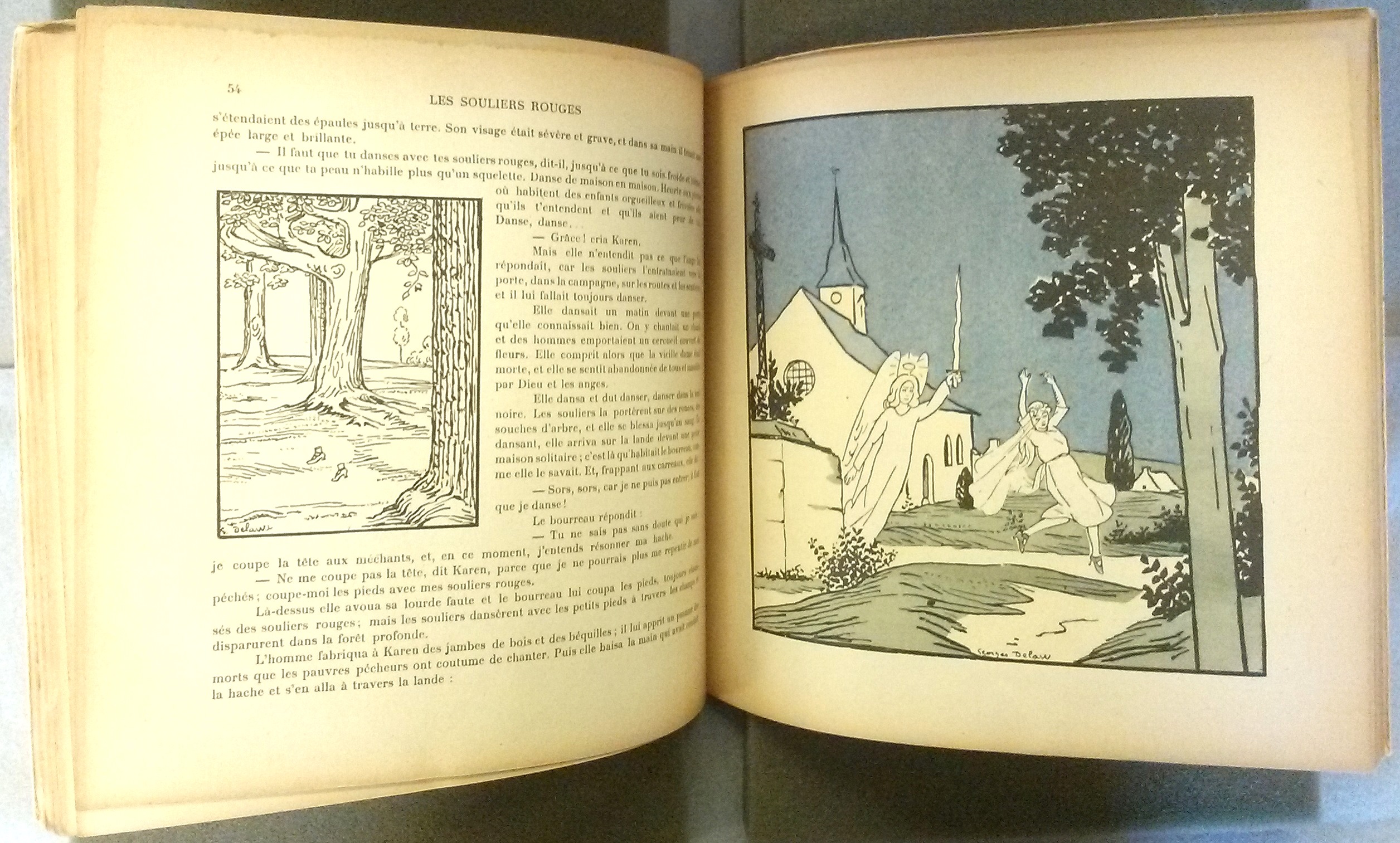

Contes d'Andersen, nouvellement traduits du danois par Wally-Anne Guégan; décors et costumes de Georges Delaw, Paris: La Sirène, 1920, p. 54.

Finally, utterly exhausted, Karen asks an executioner to cut off her feet, which dance away in the still-moving shoes. Karen learns to walk with wooden feet and crutches, and in penitence becomes the unpaid servant of a local parson’s family, not daring to try to enter the church itself after having been barred twice by the sight of her own feet still dancing in their red shoes on the doorstep. When she at last achieves complete contrition, Karen is miraculaously transported to the church and the angel who had earlier condemned her to punishment welcomes her as she rises up to heaven “where no one was there who asked after the red shoes."

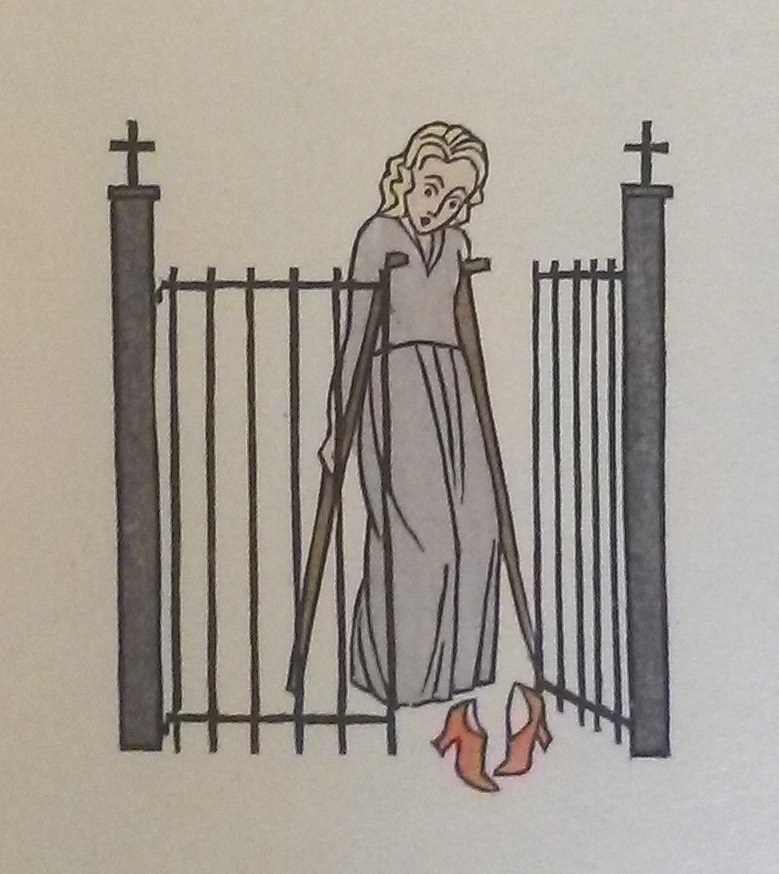

Laid-in print from

The Red Shoes, 1928.

The shocking suffering that Karen must endure as penance can lead modern readers to see “The Red Shoes” as nothing more than an overly-punitive, and even misogynistic, morality tale that forces the role of self-sacrificing angel-of-the-house upon all women, however much suffering it takes to make them conform. Certainly, conformity to social roles ascribed by protestant bourgeois society is an important thread running throughout Hans Christian Andersen’s works. However, it would be a mistake to read that as the only thread.

Literary scholar Andrew Teverson notes that Andersen frequently writes in an autobiographical mode, thereby casting himself in the role of his suffering female characters.[1] “There is really nothing in the world that can be compared to red shoes!” the narrator declares as Karen watches the princess from afar. Again in the shoemaker’s shop, he comments upon the red shoes that are Karen’s downfall by exclaiming, “how beautiful they were!” It is clear that Andersen deeply sympathises with Karen’s desire for the beautiful red shoes and all that they represent. In a direct autobiographical corollary, Anderson received a rare pair of new shoes for his confirmation and later remembered revelling in the creaking of his boots, “for thus the congregation would hear that they were new.”[2]

For Anderson, as well as Karen, shoes have resonance not only as symbols of vanity and pleasure, but of social rank and material security. Andersen’s father was an impoverished shoemaker. He once received a trial commission from a wealthy woman that would have moved the family out of urban poverty into a country village and secure employment. Sadly, the shoes were deemed unsatisfactory, his father angrily cut up the silk and leather, and the Andersens saw their hope of a better life slip away. [3]

As a child, Karen believes her good fortune to be adopted by the wealthy widow is due to the red shoes she wore at her mother’s funeral, and red shoes are further elevated when she observes them as the princess’s sole adornment. Perhaps here lies Karen’s true sin - lucky enough to aspire to the middle class, she makes the mistake of aspiring to nobility. Andersen, who saw his life as analogous to the tale of Aladdin, could undoubtedly empathise with both Karen's aspiration and her failure. Although patronage and his own literary success brought him into exalted social circles - even drinking chocolate with the king and queen - he was always painfully conscious of his own humble origins and felt himself to be an outsider. [4] Perhaps he felt that with one mis-step in the dance of high society, he - like Karen - might find his legs cut out beneath him.

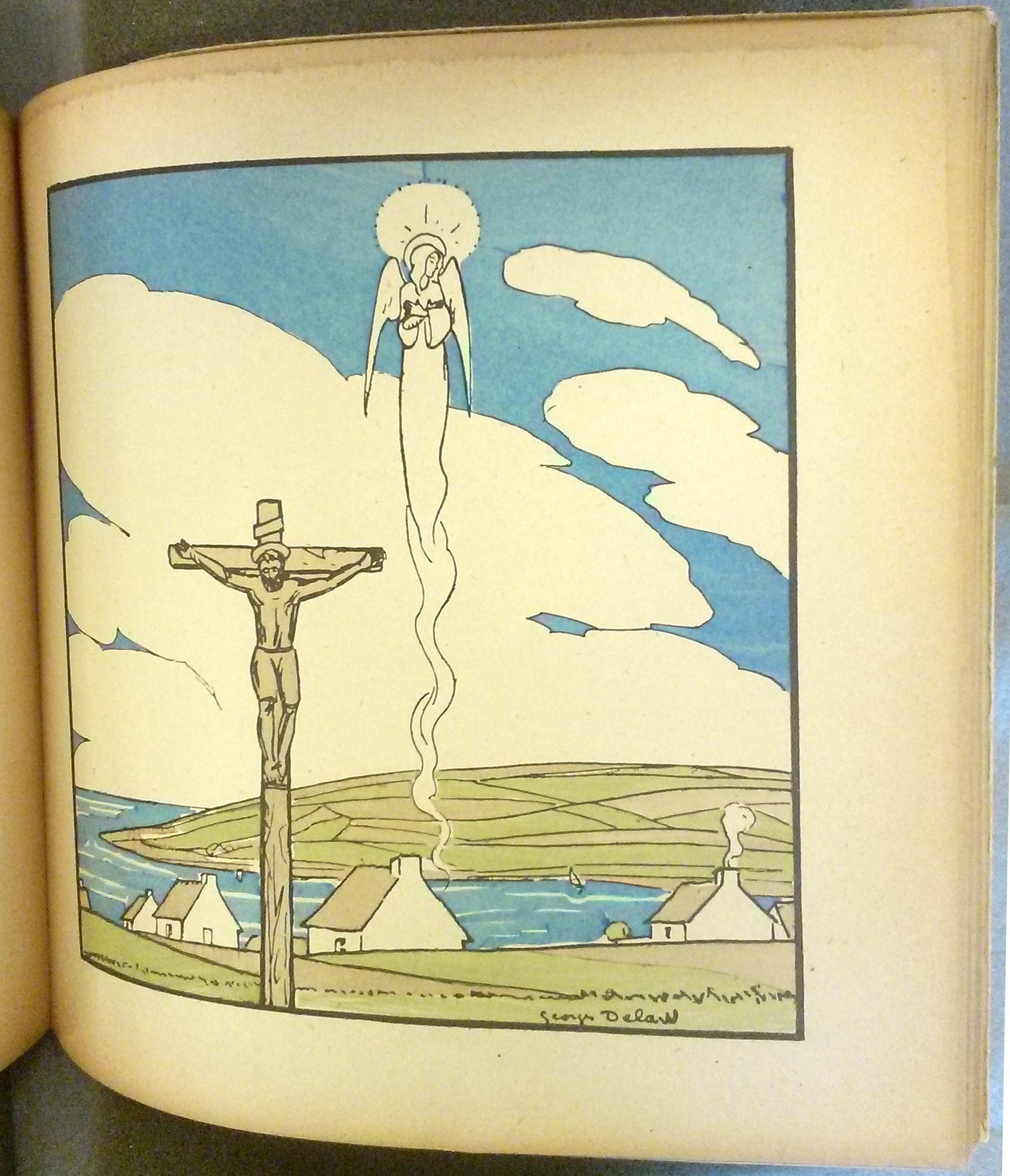

Contes d'Andersen, nouvellement traduits du danois par Wally-Anne Guégan; décors et costumes de Georges Delaw, Paris: La Sirène, 1920, p. 59.

[1] Andrew Teverson. Fairy Tale. London: Routledge, 2013. P. 80 [Hatcher Graduate | PN 3437 .T46 2013]

[2] Jackie Wullschlager. Hans Christian Andersen: The Life of a Storyteller. London : Allen Lane, 2000. P. 30. [Hatcher Graduate | 839.88 A54O W96]

[3] Jean Hersholt. "Denmark's Ugly Duckling. Andersen: The Man and His Work," In Hans Christian Andersen, The Maker of Fairy Tales. New York : The Limited Editions Club, 1942. P. 2-3. [Special Collections Children's Literature | PT 8116 .E5 H36 1942]

[4] Andrew Teverson. Fairy Tale. London: Routledge, 2013. P. 73 [Hatcher Graduate | PN 3437 .T46 2013]