Victorian poet, critic, and fiction-writer George MacDonald is best remembered today for his fantastical novels such as The Princess and the Goblin and At the Back of the North Wind. One of MacDonald’s first works for children was the short literary fairy tale “The Light Princess.” Although already in manuscript by July of 1862, "The Light Princess" was not published until it appeared within the text of Macdonald’s adult novel Adela Cathcart in 1864. It later reappeared in the collection Dealing with Fairies in 1867.[1] MacDonald himself resisted the division of his audience and maintained that he wrote, “not for children, but for the childlike, whether of five, or fifty, or seventy-five.”[2]

Although he is less a household name than his friend Lewis Carroll, George MacDonald deeply influenced many important 20th century writers, including E. Nesbit, C. S. Lewis, Madeleine L’Engle, and Maurice Sendak. Sendak, in fact, illustrated a 1969 edition of The Light Princess. Sendak's gray-toned drawings, stylistically reminiscent of engravings or etchings, lend an eerie somberness even to the earlier, light-hearted chapters of MacDonald’s meditation on the emotional trajectory from childhood to adulthood.

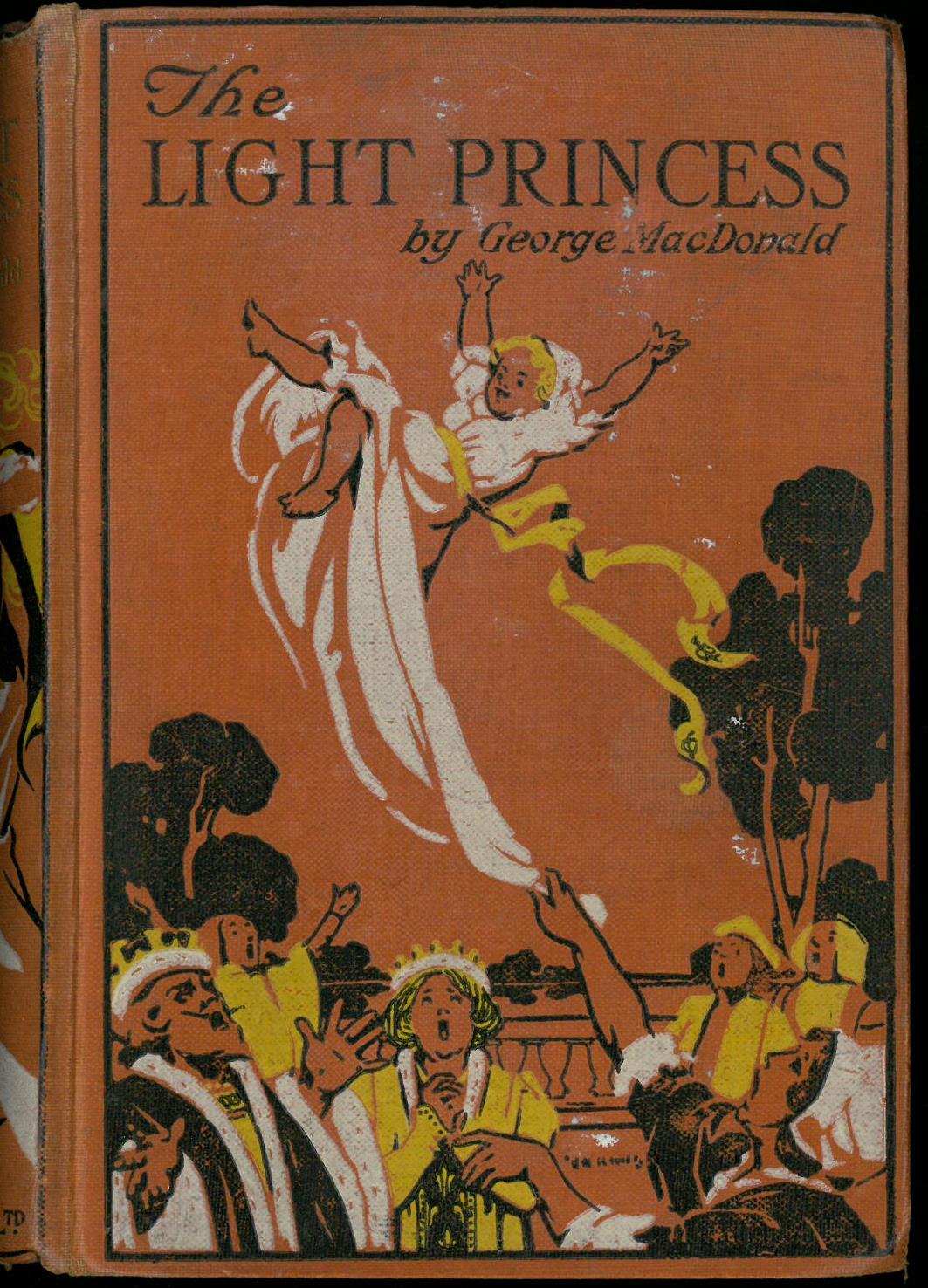

1890 edition of The Light Princess and Other Fairy Stories, published by Blackie and Son Limited. Special Collections Children's Literature PR4967 .L54 1890.

Parodying Sleeping Beauty, "The Light Princess" begins with a childless couple longing for an heir, and like Sleeping Beauty's parents, George MacDonald’s king and queen neglect to invite someone to the christening - in this case, the king’s spiteful sister, who also happens to be a very clever and powerful witch. In revenge, she curses the princess at the moment of her baptism:

Light of spirit, by my charms,

Light of body, every part,

Never weary human arms--

Only crush thy parents’ heart!

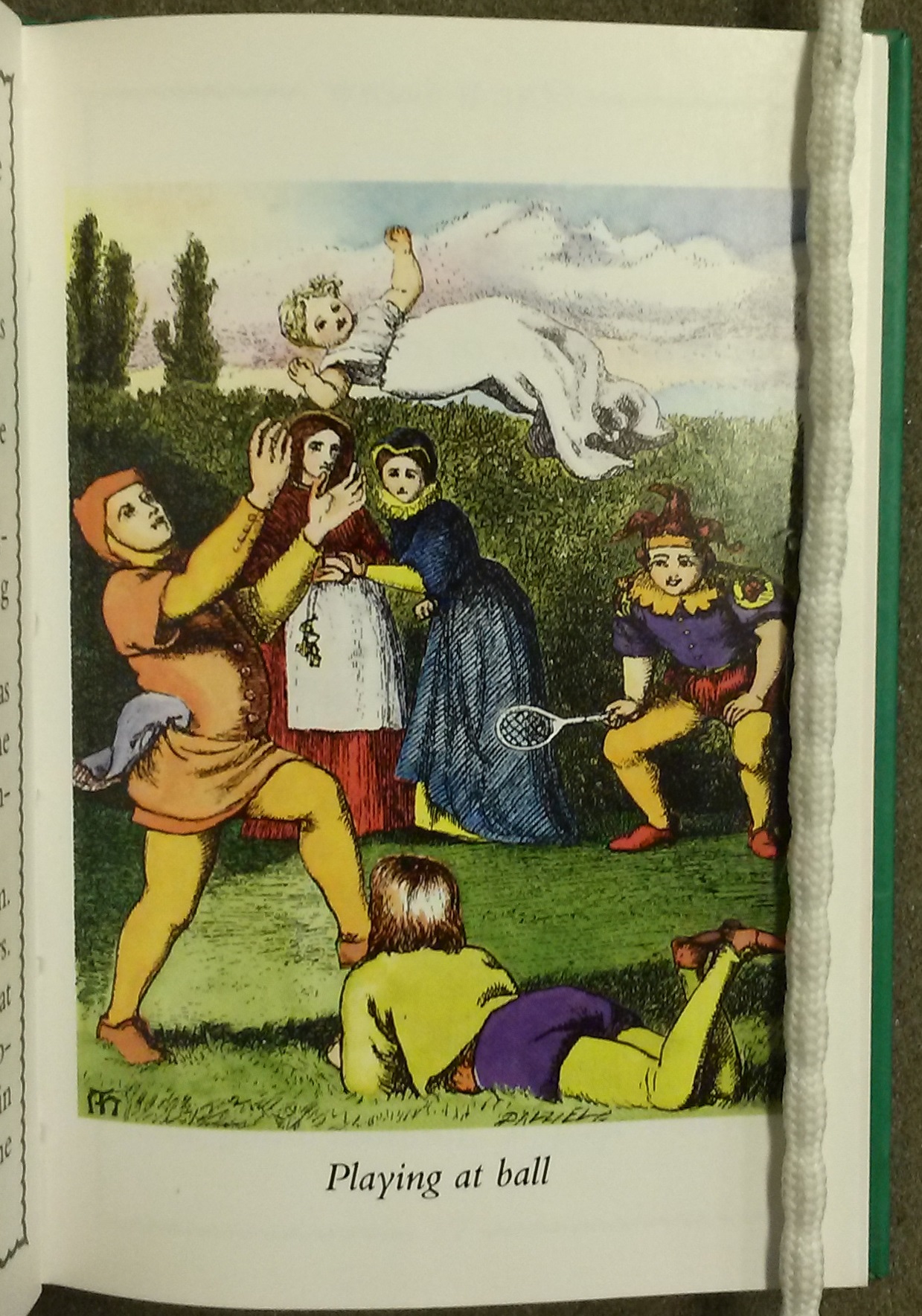

1993 Barefoot Books edition of The Light Princess. Special Collections Children's Literature PR4967 .L54 1993.

This curse deprives the princess of her gravity, resulting in misadventures from the mild inconvenience of floating up to the ceiling to the more serious hazard of being blown out the window by a mischievous wind. However, Macdonald also plays on the multiple meanings of gravity and lightness, as in this passage between the king and queen:

"It is a good thing to be light-hearted, I am sure, whether she be ours or not."

"It is a bad thing to be light-headed," answered the queen, looking with prophetic soul far into the future.

"'Tis a good thing to be light-handed," said the king.

"'Tis a bad thing to be light-fingered," answered the queen.

"'Tis a good thing to be light-footed," said the king.

"'Tis a bad thing—" began the queen; but the king interrupted her.

"In fact," said he, with the tone of one who concludes an argument in which he has had only imaginary opponents, and in which, therefore, he has come off triumphant—"in fact, it is a good thing altogether to be light-bodied."

"But it is a bad thing altogether to be light-minded," retorted the queen, who was beginning to lose her temper.

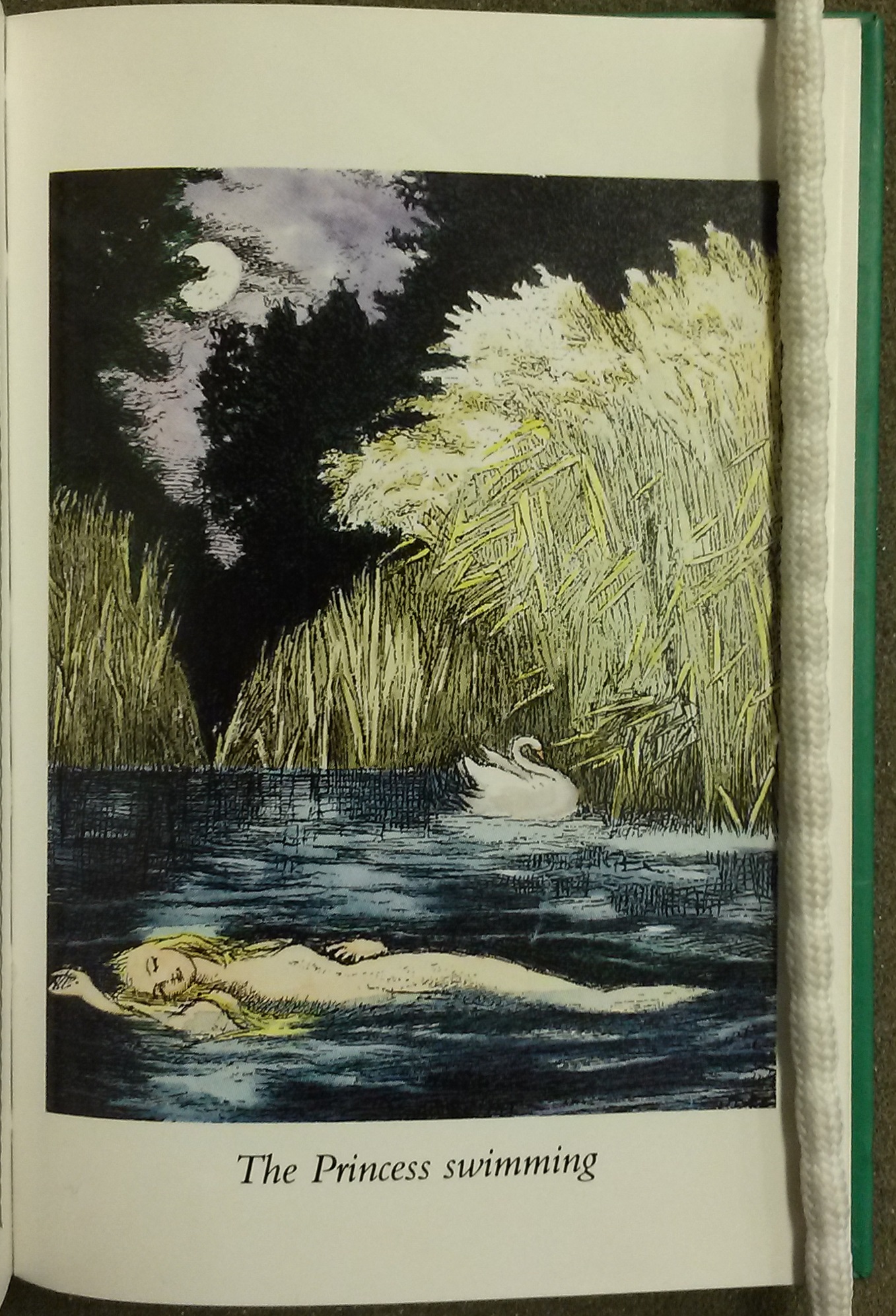

1993 Barefoot Books edition of The Light Princess. Special Collections Children's Literature PR4967 .L54 1993.

The princess proves to be both light-bodied and light-minded, unable to take anything seriously or to care deeply about anyone. The effects of the curse are mitigated only while swimming - for it is accidentally discovered that in water, the princess regains her physical gravity. She spends as much time as possible in the lake near the castle, eventually in the company of a prince-in-disguise, who joins her for nightly swims and falls in love with her. However, when he speaks to the princess about love, “she always turned her head towards him and laughed."

When the lake water begins to dry up, the princess pines away. Unbeknownst to all, the King’s sister had used a magical snake to create a drain from the lake bottom into a vast cavern below. In one of the remaining pools in the dried-up lakebed, a group of children find a golden plate covered with writing:

Death alone from death can save.

Love is death, and so is brave--

Love can fill the deepest grave.

Love loves on beneath the wave.

The reverse of the plate explains that only the body of a living man, willingly drowned, can stop the lake from draining. The prince (still in disguise) offers himself to the king as a sacrifice, providing the princess keeps him company as he waits for the the water to cover him.

The princess accepts his sacrifice as her due and is anything but gracious as they wait - complaining that it is tedious, that she wishes to sleep, and as the water begins to rise, asking “Why can’t we go and have a swim?” until the prince reminds her “I shall never swim more.” Just before the water reaches his chin, he asks the princess to kiss him, which she does and as the water covers his face, the gravity of the situation finally strikes her:

The water rose and rose. It touched his chin. It touched his lower lip. It touched between his lips. He shut them hard to keep it out. The princess began to feel strange. It touched his upper lip. He breathed through his nostrils. The princess looked wild. It covered his nostrils. Her eyes looked scared, and shone strange in the moonlight. His head fell back; the water closed over it, and the bubbles of his last breath bubbed up through the water. The princess gave a shriek and sprang into the lake.

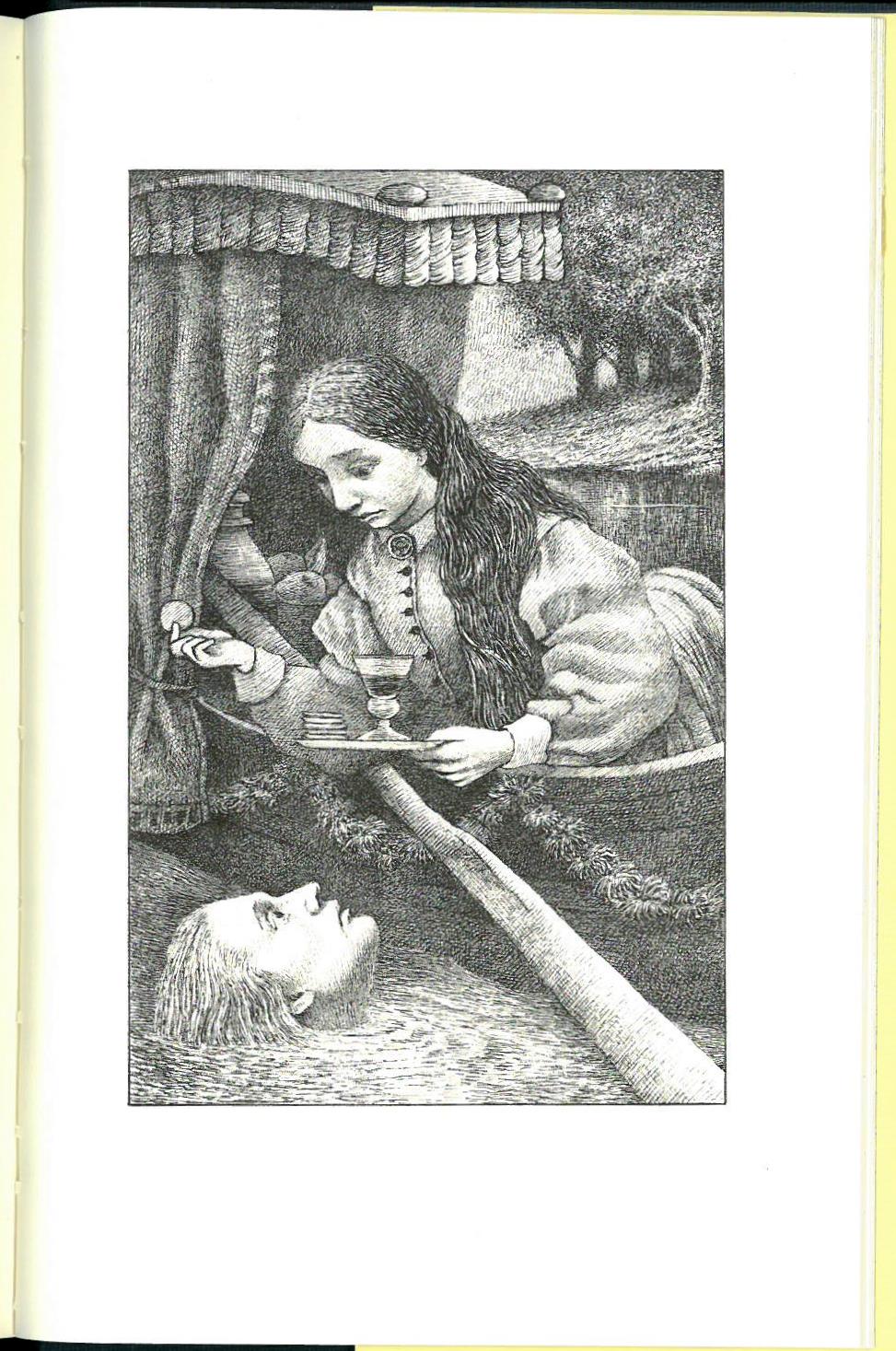

1969 Farrar edition of The Light Princess by George MacDonald, illustrated by Maurice Sendak. Special Collections Children's Literature PR4967 .L54 1969.

Realizing at long last that her companion’s life matters more to her than even her beloved lake, the princess pulls prince into the boat, rows to the shore, and struggles to revive him all through the night until, “At last, when they had all but given it up, just as the sun rose, the prince opened his eyes.”

And for the first time in her life, the princess bursts into tears. Outside, a great rain begins throughout the land and not only the lake, but all the rivers are replenished. And when the princess stops crying and tries to stand up, she falls down, to her old nurse's surprise and delight:

"My darling child! she's found her gravity!"

"Oh, that's it! is it?" said the princess, rubbing her shoulder and her knee alternately. "I consider it very unpleasant. I feel as if I should be crushed to pieces."

"Hurrah!" cried the prince from the bed. "If you've come round, princess, so have I. How's the lake?"

"Brimful," answered the nurse.

"Then we're all happy."

"That we are indeed!" answered the princess, sobbing.

The prince and princess are betrothed, the princess learns to walk instead of float, and in time they have sons and daughters, “not one of whom was ever known, on the most critical occasion, to lose the smallest atom of his or her due proportion of gravity.”

[1] Jan Susina, The Place of Lewis Carroll in Children's Literature (New York: Routledge, 2010): 29.

[2] Roderick McGillis. "George MacDonald," Dictionary of Literary Biography Database. Volume 163: British Children's Writers, 1800-1880. Ed. Meena Khorana, 1996.