"Beauty and the Beast" is one of the most popular and frequently republished fairy tales. While it has roots and antecedents in animal groom folklore and classical mythology, such as the tale of Cupid and Psyche, the specific characters and narrative elements that compose the tale we know as “Beauty and the Beast” have their origin in the literary fairy tale “La Belle et la Běte” written in 1740 by Madame Gabrielle-Suzanne de Villeneuve.

The fairy who speaks to Beauty in her dream. Athur Quiller-Couch, Edmund Dulac (illus.), Sleeping Beauty and Other Fairy Tales from the Old French (London: Hodder & Stoughton, 1910).

De Veilleneuve was born into an aristocratic family, but found herself in precarious financial straits after the death of her gambling husband in 1711. Eventually, she moved to Paris, where she published a novella in 1734, collections of fairy tales in 1740-41 and 1745, and a full novel in 1753. “La Belle et la Běte” appeared as the first story in La jeune amériquaine, ou Les contes marins (The Young American Girl, or the Marine Tales, 1740–41). De Veilleneuve’s novella is a complex tapestry in which the familiar core narrative of a girl who sees through a Beastly exterior and is rewarded by marrying the Prince within, is surrounded by tales of the Beast’s enchantment and Beauty’s genealogy, as well as elaborate dream sequences and the interactions of several fairies.

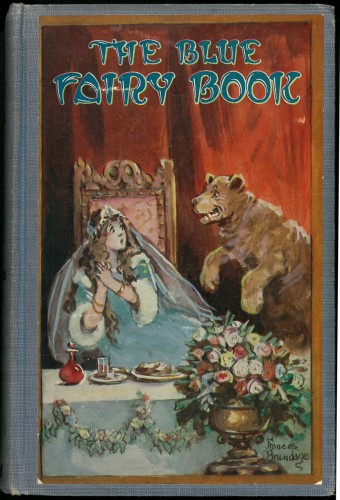

In 1756, Jeanne-Marie Leprince de Beaumont revised the story for younger children in her Magasin de Enfants (Young Misses Magazine). De Beaumont removed most of the subplots, dream sequences, all but one fairy, and overt references to sexuality. In De Veilleneuve’s original, the Beast explicitly asks Beauty “May I sleep with you tonight,” whereas in de Beaumont’s version for younger children, the beast instead asks “Will you marry me.” The Beast's willingness to take "no" for an answer is particularly significant in the context of the legal and familial norms of the 18th century, a time when rights to women's bodies passed from fathers to husbands, rarely residing with women themselves. More explicitly didactic and conventional than de Veilleneuve, de Beaumont’s version emphasizes Beauty’s patience, obedience, and hard work. It was this version of the tale that was translated into English and most influenced various illustrated versions throughout the 19th century. One notable exception is Andrew Lang’s The Blue Fairy Book, which contains Lang’s own abridgement of de Veilleneuve’s tale. First published in 1889, it remained popular well into the 20th century, as shown by this 1918 edition published by Saalfield Publishing Company in Akron, Ohio.

Cover illustration. Andrew Lang, The Blue Fairy Book (Akron, OH: Saalfield Publishing Co., 1918). Children's Literature Collection.

Andrew Lang, The Blue Fairy Book

(Akron, OH: Saalfield Publishing Co., 1918).

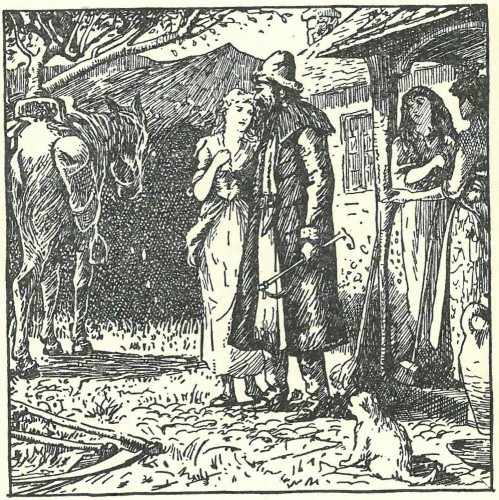

In Lang’s version of "Beauty and the Beast," a rich merchant with six sons and daughters unexpectedly loses his fortune and retreats to a small country cottage. When he receives word that one of his ships - believed to be lost - has come safely into port, he returns to the city with intentions of bringing rich gifts back to his children, all save Beauty, who requests only his safety and a rose. Unfortunately, the ship does not reverse the merchant’s fortunes and he must return poorer than ever. On his return journey, he is lost in a blizzard in the forest and stumbles upon a sumptuous palace where invisible servants provide for all his needs. As he leaves the next morning, the merchant picks a rose from the hedge, thereby enraging the Beast, who appears to threaten him with death. Upon hearing the merchant’s story, the Beast offers to spare his life if one of his daughters willingly comes to live at the palace in his place.

Andrew Lang, The Blue Fairy Book

(Akron, OH: Saalfield Publishing Co., 1918).

After the merchant’s return home, Beauty insists on taking her father’s place. During her first night in the palace, Beauty dreams of a handsome prince who comforts her and begs her to find him, however disguised, and then of a beautiful lady who warns her not to be deceived by appearances. In the coming days and weeks, Beauty explores the wonders of the enchanted palace and is joined for dinner each night by the beast, who asks her to marry him. In time, Beauty becomes homesick and asks to visit her family; the Beast reluctantly agrees but enjoins her to return at the end of two months. Beauty finds herself missing the palace and her companion, but delays her return until the handsome prince warns her in a dream that the Beast is dying. She then returns to the palace and searches frantically for the Beast until she comes across him lying in a cave, where she revives him with water from a nearby fountain and declares her love. When she agrees to marry him, the Beast transforms into her dream prince and the stately lady from her dreams arrives with the Beast’s mother to approve the match.

The use of archetypal names for its central characters - Beauty and the unnamed Beast - has offered writers and illustrators broad creative scope in retelling this story, depicting and describing contemporary notions of both physical and internal beauty and imagining the world of the Beast’s enchanted palace. Three recent illustrated retellings from the Children’s Literature Collection show a range of interpretations, although all of them follow the trend begun by de Beaumont in focusing the narrative tightly upon Beauty and the Beast’s interactions by removing sub-plots, dream sequences, and ancilliary characters.

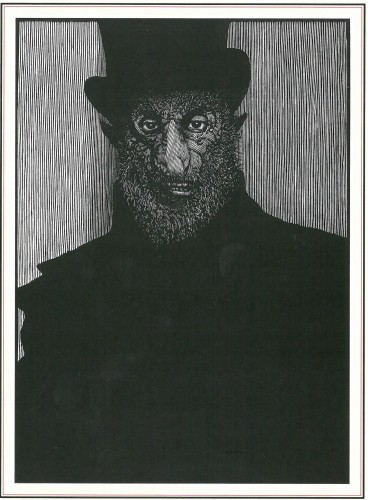

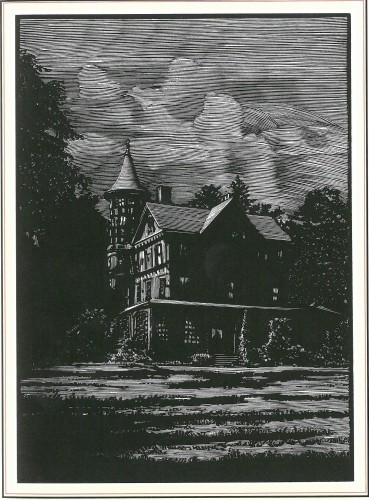

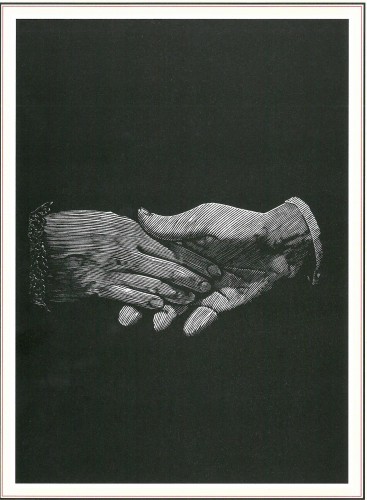

Author and poet Nancy Willard (whose archive resides in the University of Michigan Special Collections Library), published a re-telling of this beloved tale in 1992. Set in New York City in the early 1900s and accompanied by black and white illustrations from master wood-engraver Barry Moser, this version is a distinct departure from the fanciful flavor of Lang’s rainbow fairy books. Without eliminating the existence of magic, Moser and Willard ground the story in realism, including the precise location of the merchant’s “splendid townhouse,” which “looked out on Central Park on Fifth Avenue at Fifty-ninth.” Moser’s beast wears a top-hat and black coat and lives in a gloomy, but not fantastical mansion. And in a somewhat unusual choice, the Beast’s transformation is depicted only through an image of his hand reaching out for Beauty’s, leaving his human form to the reader's’ imagination.

The Beast. Nancy Willard, Barry Moser (illus.) Beauty and the Beast (San Diego: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1992). Lee Walp Family Juvenile Book Collection.

The Beast's mansion. Nancy Willard, Barry Moser (illus.) Beauty and the Beast (San Diego: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1992). Lee Walp Family Juvenile Book Collection.

Beauty and the Beast's hands clasping after his transformation into a man. Nancy Willard, Barry Moser (illus.) Beauty and the Beast (San Diego: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1992). Lee Walp Family Juvenile Book Collection.

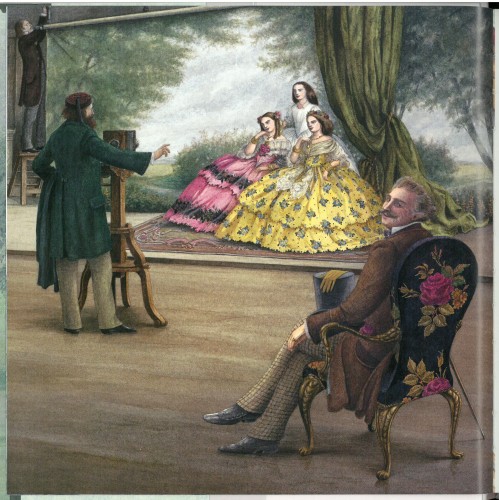

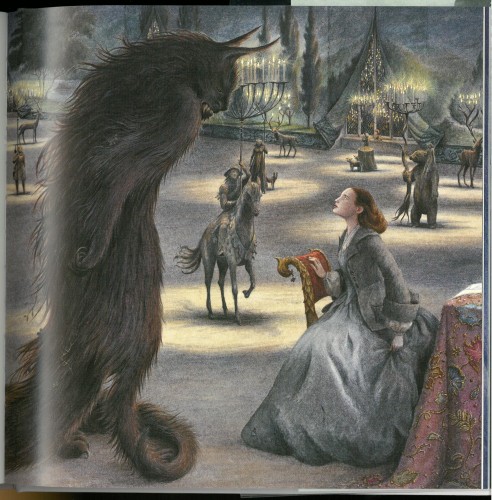

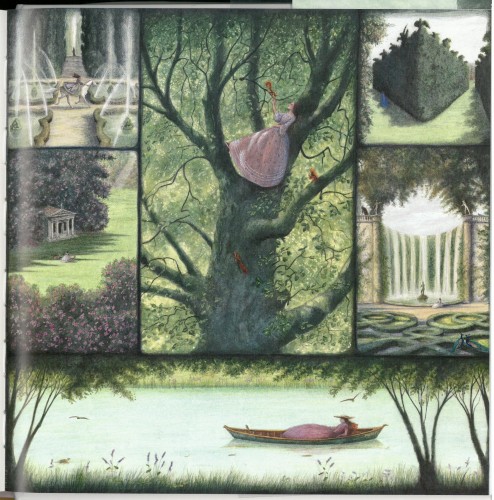

The 2006 edition re-told by Max Eilenberg and illustrated by Angela Barrett is another example of "Beauty and the Beast" grounded in a particular time - in this case the mid-19th century. The tone, however, is very different, perhaps more reminiscent of the soft colors and rich textures of Edward Dulac's illustration style (seen above. Eilenberg’s narrative revels in lively dialog and descriptions of the enchanted palace, while Barrett’s soft-textured but richly detailed illustrations follow the narrative action from the stifling Victorian interiors of the merchant’s city mansion to the dream-like environment of the shadowy feline Beast’s palace. Of particular note are the panel illustrations that depict Beauty’s explorations of the Beast's idyllic gardens.

Beauty's life in the city. Max Eilenberg, Angela Barrett (illus.), Beauty and the Beast (Cambridge, MA: Candlewick Press, 2006).

Beauty meets the Beast. Max Eilenberg, Angela Barrett (illus.), Beauty and the Beast (Cambridge, MA: Candlewick Press, 2006).

Beauty explores the Beast's gardens. Max Eilenberg, Angela Barrett (illus.), Beauty and the Beast (Cambridge, MA: Candlewick Press, 2006).

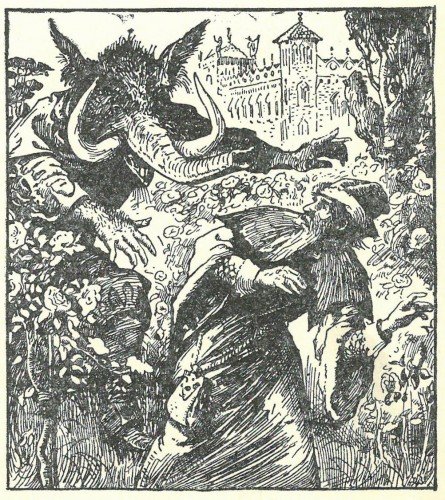

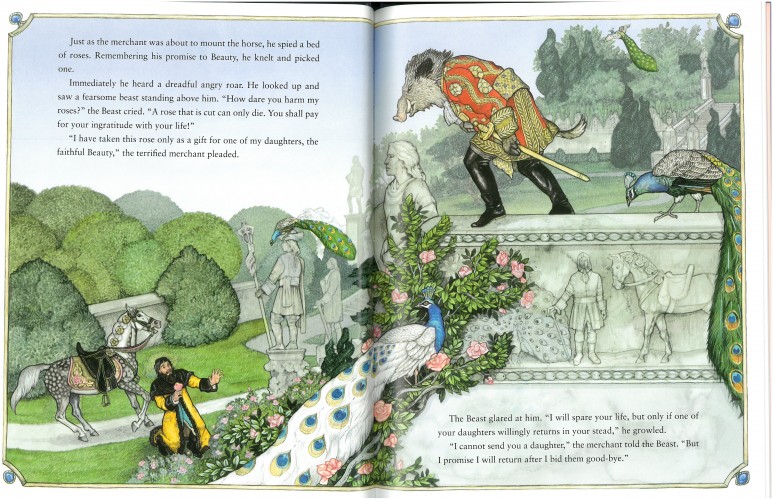

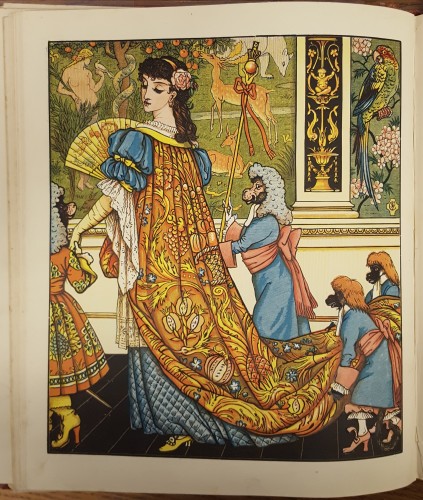

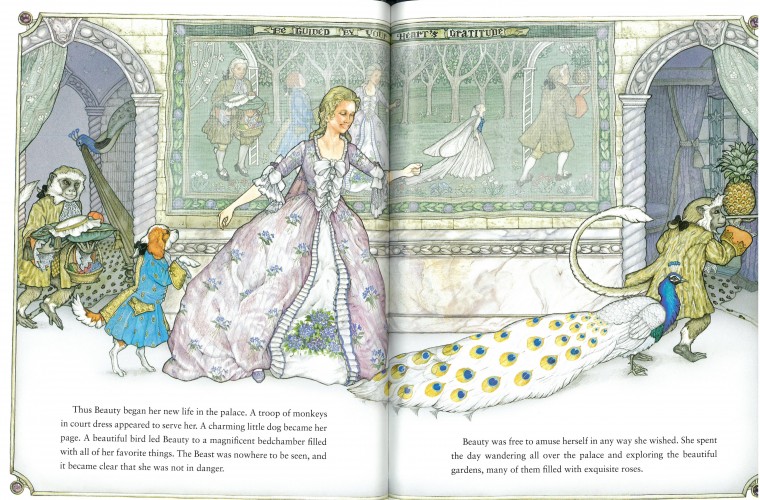

Finally, Jan Brett’s "Beauty and the Beast" (first published in 1989 and re-issued in 2011) offers a simpler, shorter narrative with less elaboration, but showcases Brett's characteristic use of tapestry-like detail. Despite his porcine head, Brett’s beast is much more human-like in his appearance and posture than Barrett’s shadowy feline, and rather than exploring the grounds in splendid isolation, a smiling Beauty is waited upon by dogs and monkeys in frock coats, altogether giving her work a lighter atmosphere. Although distinct in many respects, Brett's rendition of the Beast and of his servants seems much inspired by the Victorian illustrations of Walter Crane in Goody Two Shoes' Picture Book (1874).

The Beast confronts the merchant. Walter Crane, Goody Two Shoes Picture Book (London: George Routledge and Sons, 1874). Lee Walp Family Juvenile Book Collection

The Beast confronts the merchant. Jan Brett, Beauty and the Beast (New York: G.P. Putnam's Sons, 2011). Gift of William A. Gosling.

Beauty is attended by servants in the Beast's palace. Walter Crane, Goody Two Shoes Picture Book (London: George Routledge and Sons, 1874). Lee Walp Family Juvenile Book Collection

Beauty is attended by servants in the Beast's palace. Jan Brett, Beauty and the Beast (New York: G.P. Putnam's Sons, 2011). Gift of William A. Gosling.

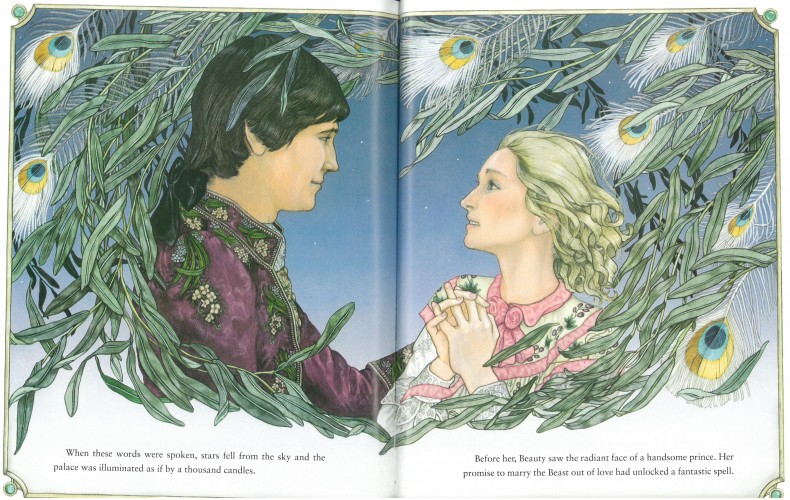

Brett also brings her own originality to the illustrations, however, as with her integration of peacocks and feathers - symbolizing vanity and surface appearances that Beauty must overcome - throughout the story, from a peacock-headed harp glipmsed through the doorway in the illustration above, to feathered fronds intermixed with the tree leaves surrounding the Beast’s transformation scene below.

The Beast transforms into a prince. Jan Brett, Beauty and the Beast (New York: G.P. Putnam's Sons, 2011). Gift of William A. Gosling.