Our last Fairy Tale Friday recounted Hans Christian Andersen’s "The Red Shoes" - a story about a girl whose vanity led to the loss of her feet and, ultimately, her life. Footwear features prominently again in today’s fairy tale. However, unlike Karen’s cursed dancing shoes, Aschenputtel (or Ashputtel) finds that her golden slippers are the vehicle of her own reward and of revenge against her cruel stepsisters.

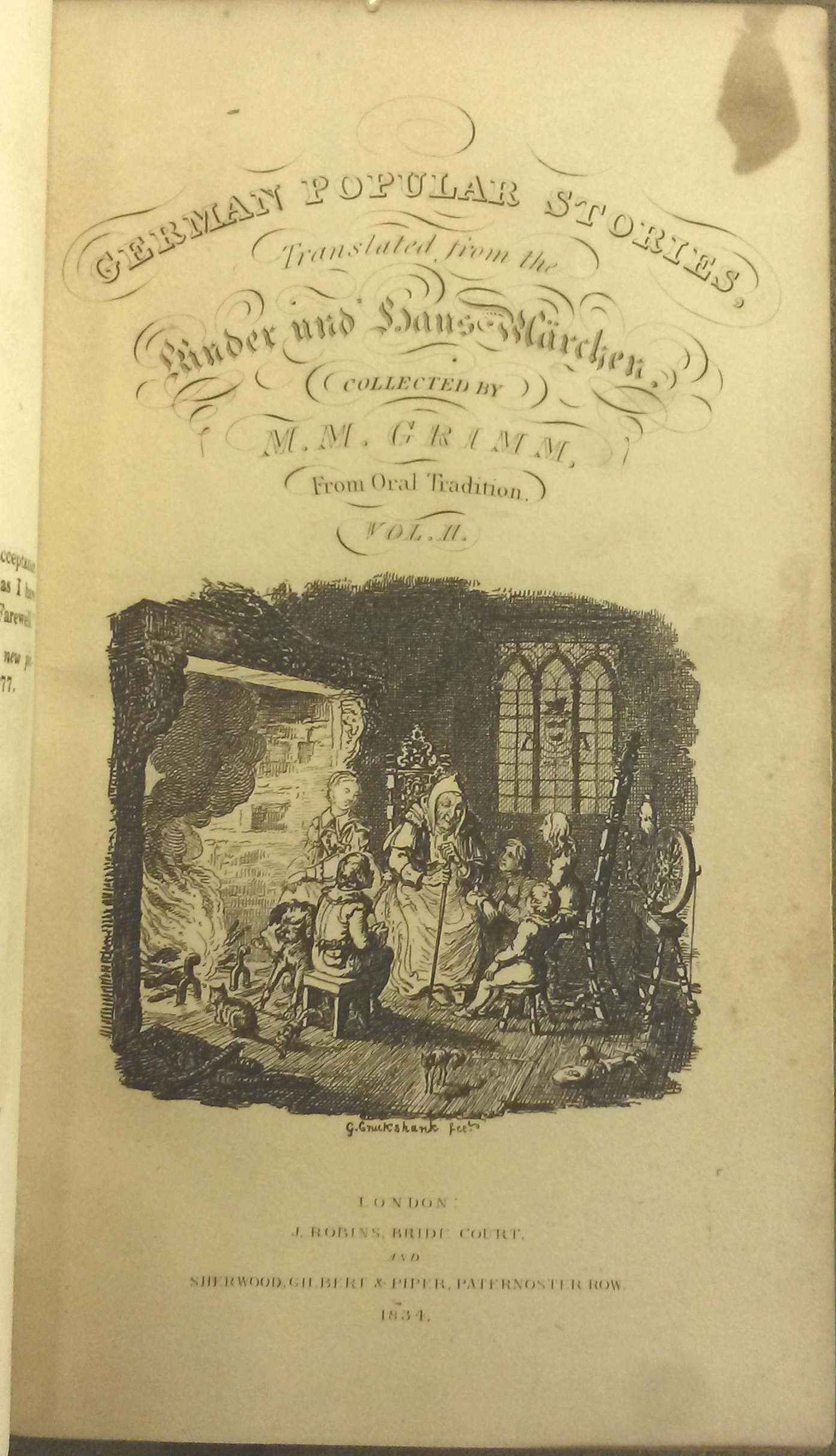

German Popular Stories: Translated from the Kinder und Haus-Märchen collected by M.M. Grimm. London : J. Robins : Sherwood, Gilbert & Piper, 1834. Special Collections Children's Literature

PT 2280 .A2 M37 1834.

As presented in the 1834 edition of German Popular Stories, translated by Edgar Taylor from Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm’s Kinder und Hausmärchen, the story of Ashputtel begins with a dying mother promising her daughter, “I will look down from heaven and watch over you.” The girl’s father remarries soon after his wife’s death, and the little girl is relegated to a servant’s role and forced to sleep “by the hearth among the ashes,” which gives her the name Ashputtel. After she plants a hazel tree on her mother’s grave, a little bird builds its nest there, which talks to her and brings her "whatever she wished for.”

Several years later, the king of that country declares a three day festival for his son to choose a bride, Ashputtel begs to join the family and her stepmother bargains that she might go if she sorts first one and then two bowls of peas from the ashes. Assisted by doves and other birds, Ashputtel completes the impossible tasks, but is nonetheless left at home. Taking matters into her own hands, she goes to her hazel tree and chants

Shake, shake, [hazel]-tree

Gold and silver over me!

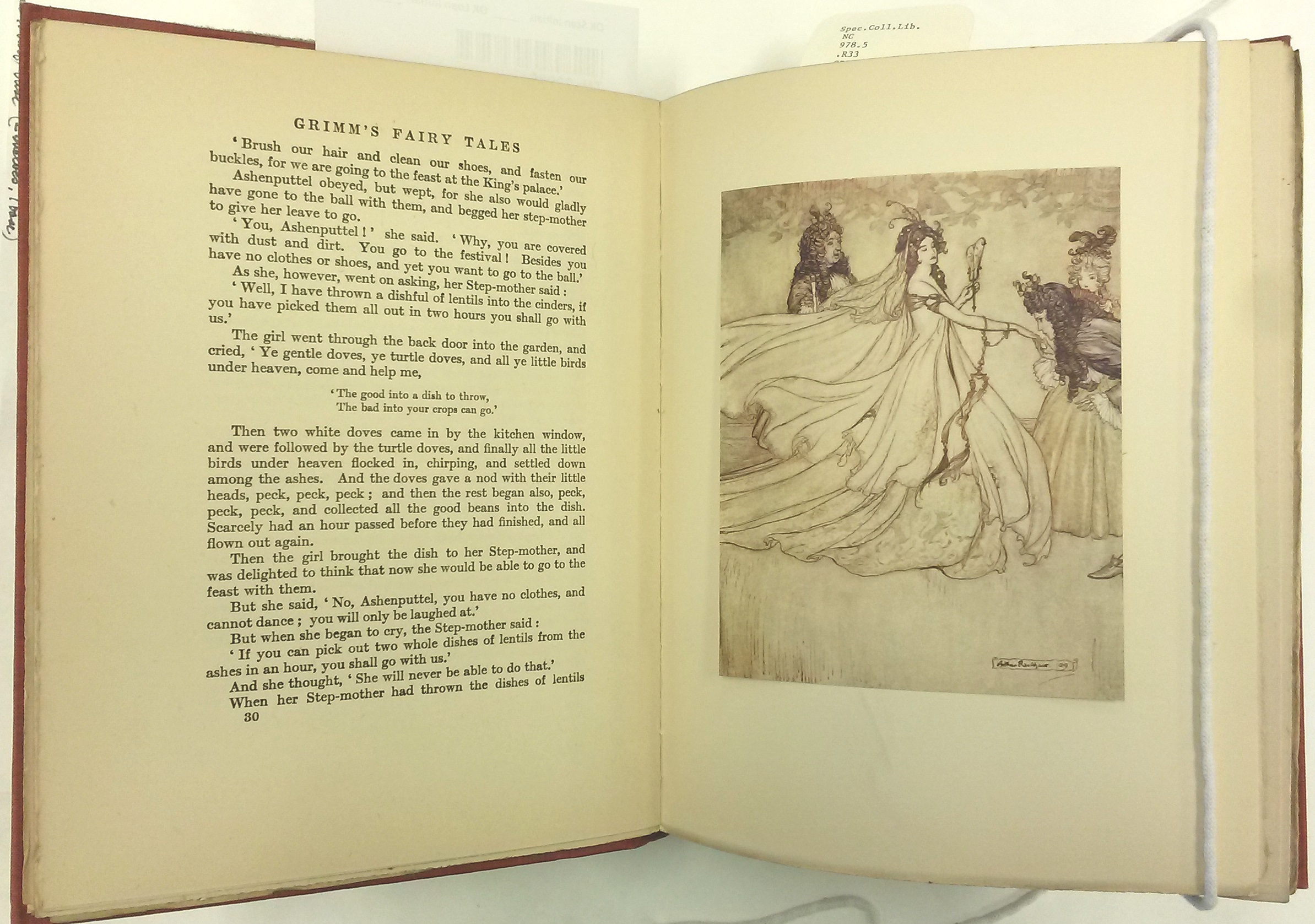

At the festival, the prince and Ashputtel dance together all evening, but to protect her identity, she departs by leaping into a pigeon house and climbing down the other side (an impressive feat in a ballgown). This repeats twice more (with minor variations and ever-finer clothing), but as Ashputtel slips away on the last night of the festival, she drops one of her golden slippers.

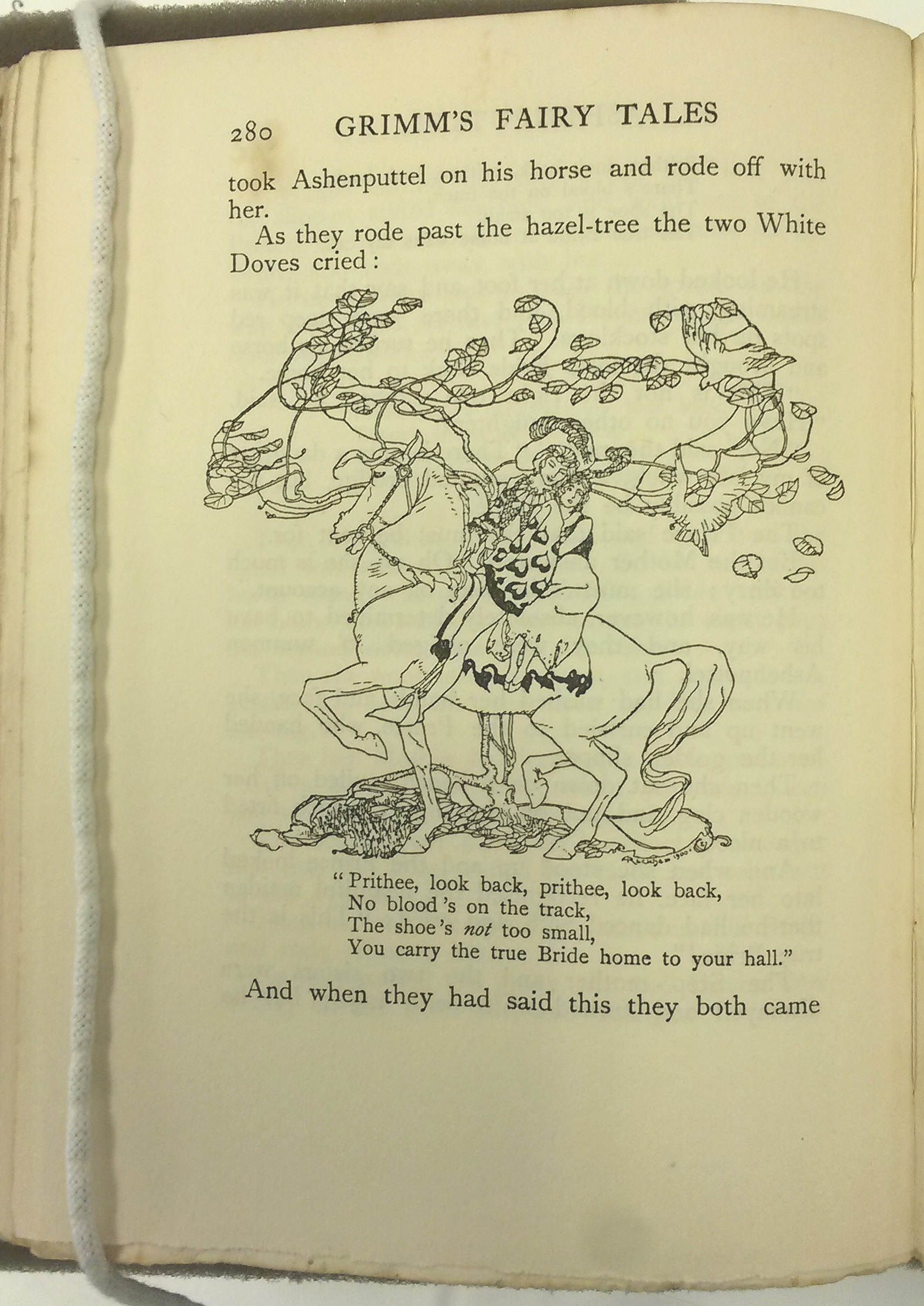

When the prince comes seeking his mystery lady, one step sister forces her foot into the shoe by cutting off her big toe, but the dove in Ashputtel’s hazel tree calls out:

Back again! back again! look to the shoe!

The shoe is too small, and not made for you!

Prince! prince! look again for thy bride,

For she’s not the true one that sits by your side.

The second step sister tries a similar trick with her heel, but again the dove calls the prince’s attention to how “the blood streamed so from the shoe that her white stockings were quite red.” Finally, Ashputtel is allowed to come forward to try on the shoe, and when the prince “drew near and looked at her face he knew her and said, ‘This is the right bride.’”

The 1834 edition ends with the white dove in the hazel tree affirming the prince’s choice before flying to Ashputtel’s right shoulder:

Home! home! look at the shoe!

Princess! the shoe was made for you!

Prince! prince! take home thy bride,

For she is the true one that sits by thy side!

However, in the original German and in many later translations, Ashputtel’s doves further punish the stepsisters by pecking out their eyes as they escort her as bridesmaids on her wedding day.

Snowdrop & Other Tales by the Brothers Grimm; Illustrated by Arthur Rackham. New York : E.P. Dutton & Company, 1920. Special Collections General and Rare NC 978.5 .R33 G75 1920

The broad outlines of this story probably sound familiar, but you might be wondering, “wait, where’s the fairy godmother? Wasn’t there a pumpkin and some mice somewhere in there? And isn’t the foot mutilation and eye-pecking a bit macabre for a children’s story?”

In fact, Aschenputtel is part of a large and diverse family of “Cinderella” tales from throughout the world that share the elements of a mistreated child, rescue by a representation of a deceased mother, and recognition and restoration of status through marriage. One of the oldest recorded literary Cinderellas dates back to 9th century China - in this case, the wish-granting entity is a man from the sky working through the bones of the protagonist’s pet fish (cruelly eaten by her stepmother).[1] "Aschenputtel" is a Germanic variant collected and re-written by Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm in the early 19th century, which itself undoubtedly owes a debt to earlier printed tales, as well as to oral tradition.

Fairy Tales of the Brothers Grimm: A New Translation by Mrs. Edgar Lucas; With Illustrations by Arthur Rackham. London : Freemantle & Co. ..., 1900. Special Collections General and Rare NC 978.5 .R33 K56 1900

On the other hand, the fairy-godmother-and-glass-slipper version that English speakers are likely familiar with is derived from “Cendrillon,” a literary fairy tale written for a French salon audience in the 17th century by Charles Perrault. “Cendrillon” was translated into English in the 18th century, but came into its own in the early 19th century when it entered the repertoire of English pantomime theater.

Numerous illustrated editions for children were published in the following decades, altering the story along the way by making the step-sisters ugly in appearance as well as behavior, and by redacting even Cinderella’s small moments of self-direction like asking to borrow her step sister’s gown to see the prince or suggesting that her fairy godmother transform a rat into a coachman.

Art historian Bonnie Cullen argues that Perrault’s Cinderella - rather than Grimms’ Ashputtel or D’Aulney’s Finette - was embraced because her comparative passivity (and lack of blood or gore) made her a more suitable vehicle for Victorian notions of domestic femininity.[2]

Perrault’s tale (or a modified version thereof) was sealed as "the" canonical Cinderella for American audiences when it was used as the basis for Disney’s 1950 film Cinderella (itself recently remade as a live-action film). However, for those who find Cendrillon/Cinderella’s helpless damsel-in-distress act a little too cloying, Ashenputtel’s “grimmer” aspect may provide a refreshing bite.

[1] Bonnie Cullen, “For Whom the Shoe Fits: Cinderella in the Hands of Victorian Illustrators and Writers,” The Lion and the Unicorn 27, no. 1 (2003):58.

[2] ibid. 74