This post is from Archives Assistant, Nora Dolliver

We are very excited to announce that the Joseph A. Labadie Collection has acquired a new set of Emma Goldman papers. These documents have until recently been in private hands. It is rare for previously unknown Goldman materials to surface. Comprised primarily of letters between Goldman and her comrade Warren Starr Van Valkenburgh (known to Goldman as “Van”), this archive is a companion to a collection we acquired in the 1950s of some of Van Valkenburgh’s papers. They will be in good company at the Labadie along with our other Goldman materials (see a list of our published and unpublished finding aids here, including her Russian passport and her suitcase). In addition to the letters between Goldman and Van, the collection includes materials related to the political activities and committees the two were involved in, including the Sacco-Vanzetti Defense Committee, correspondence with other anarchists and public figures, and printed materials including pamphlets and newspaper clippings.

Goldman’s letters to Van, a fellow anarchist and writer who edited the anarchist journal Road to Freedom, span over a decade, though the bulk are from the late 1920s. They offer a window into Goldman the writer as she worked on her two-part autobiography Living My Life. Van assisted her with practical aspects of her work, by helping promote her speaking events and connecting her with publishers. He also served as a sounding board for Goldman’s triumphs and frustrations as she gave lectures and wrote an autobiography in exile from her adopted homeland of the United States. After giving a particularly difficult lecture in Toronto, an exhausted Goldman wrote to Van: “The baby was born at last. I am sure if labour pains are anything like what I went through in mental agony the last two weeks I cannot blame women for not wanting to have so many kids.”

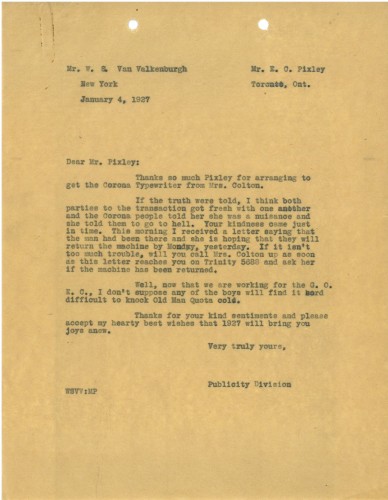

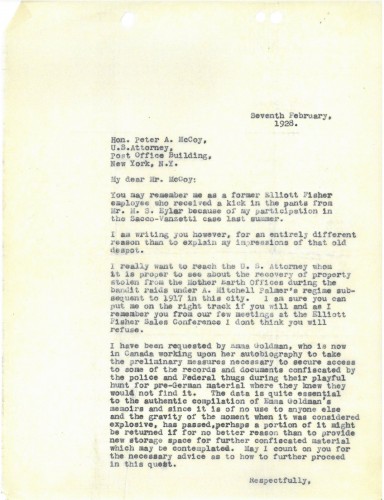

Both Goldman and Van display quick wits and, at times, quick tempers—-sometimes in the same letter. In one memorable exchange, Goldman addresses a letter to “Dear pedantic Van” before explaining in typically typo-ridden fashion why she cannot possibly improve her typing as he has asked her to: “I know I am a rotten typist, in fact, the more I try, the worst I am, and as to spelling, well, I have this in common with all great people [...] But you must bear in mind that any fool can learn to spell and type, it takes brains to be able to [think?] and ability to be able to write.” Apparently unconvinced by this argument, in an effort to both improve the legibility of her letters and to help her as she wrote her autobiography Van arranged to have Goldman’s typewriter replaced. If a rueful letter he sent to a contact in Toronto is any indication, he may have underestimated the patience this task would require: “If truth were told, I think both parties to the transaction got a bit fresh with one another and the Corona people told her she was a nuisance and she told them to go to hell.” If Goldman was a nuisance, her correspondent could certainly be one himself, often to useful ends. In a letter to the U.S. Attorney’s office, Van requested the return of the materials the police had confiscated when they raided the offices of Goldman’s journal Mother Earth, because Goldman wanted to use the documents in the research for her memoirs. Perhaps realizing that the Attorney’s Office might find this reason less than persuasive, Van added: “perhaps a portion of it might be returned if for no better reason than to provide new storage space for further confiscated materials which may be contemplated.”

Despite the frequent flashes of humor, the letters are also at times remarkably poignant. Reflecting on a comment from Van on borders and boundaries, Goldman, nearing her tenth year in exile from the U.S., writes: “I realize there are any amount of much more subtle forces which separate not only countries from countries, but individuals from individuals, and even friends from friends, but all these philosophic contemplations have no meaning when one’s heart yearns for something which is within a stone’s throw and yet one must turn from it. You also write that the struggle is worth while no matter what the outcome. That is precisely the reason why I go on struggling.”

Letter from Van Valkenburgh to a Toronto contact thanking him for his assistance in fixing Goldman's typewriter.

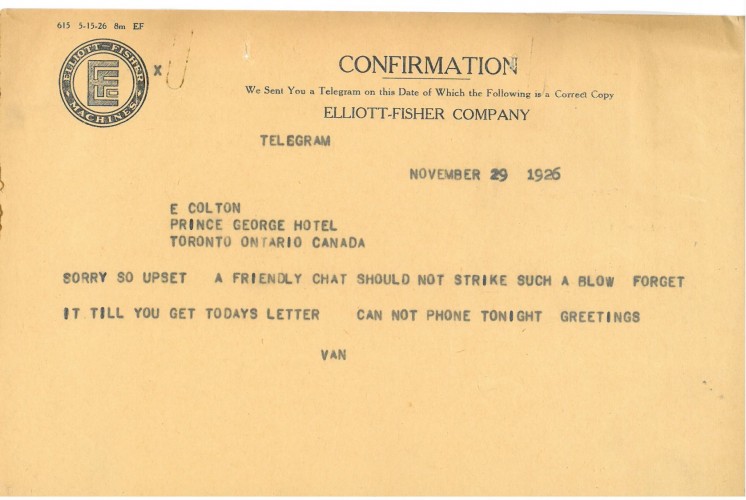

A 1926 telegram from Van Valkenburgh to Goldman (using her married name, Emma Colton)

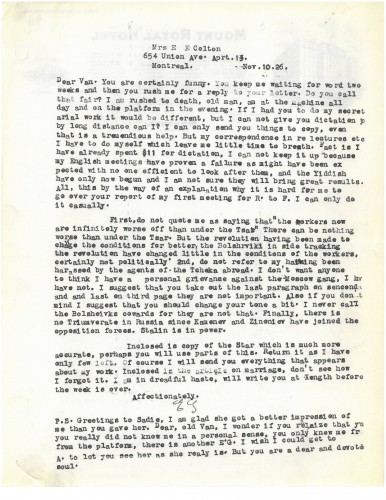

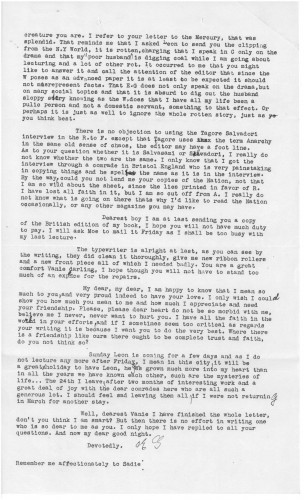

A November 1926 letter from Goldman to Van Valkenburgh discussing a report in Road to Freedom about a speech Goldman had given in Canada (?) on the political situation in the Soviet Union.

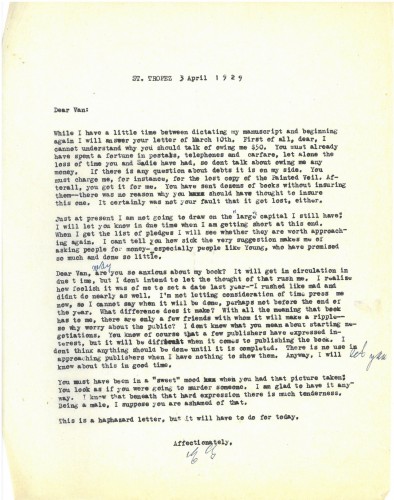

April 1929 letter from Goldman to Van Valkenburgh discussing the publicity around Living My Life, sent from St. Tropez, France.

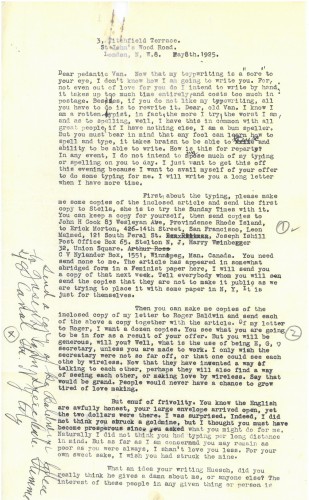

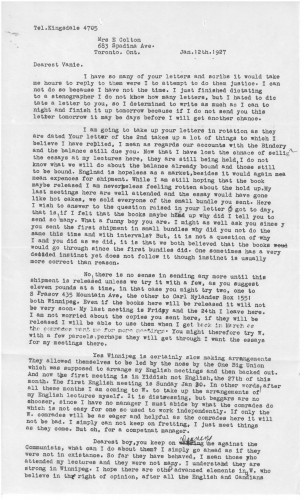

A two-page letter from Goldman to Van Valkenburgh, written from London in 1925, in which she discusses her typing and her activities with the British Committee for the Defense of the Political Prisoners in Russia.

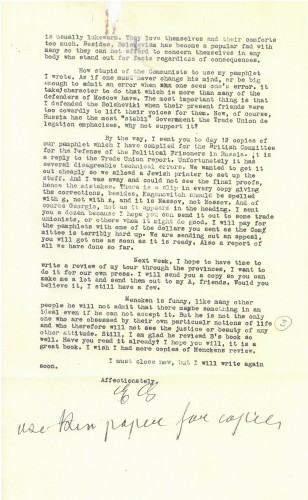

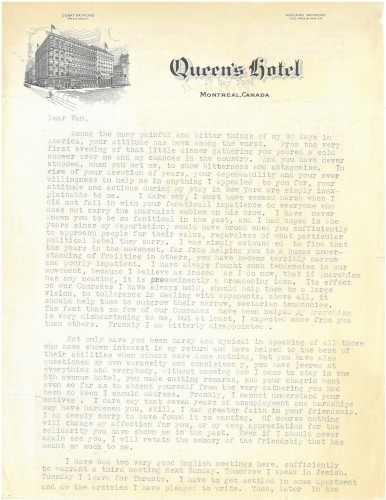

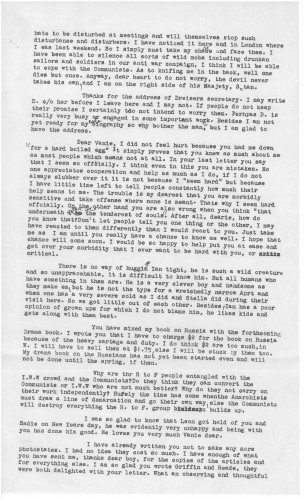

Two-page letter from Goldman to Van Valkenburgh following her 1934 visit to the U.S. (her first and last since her deportation in 1919), expressing disappointment over an argument the two had. Other letters in the collection suggest that the two had a falling-out over their differing opinions on whether anarchism had a future in the U.S.

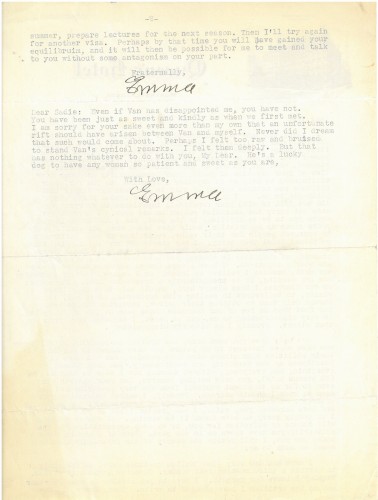

3-page letter written in 1927 from Goldman (using her married name, Colton) to Van Valkenburgh. She writes about the lectures she plans on giving in Winnipeg and why she is not afraid of Communists, along with several personal matters and discussion of her forthcoming publications.

A 1928 letter from Van Valkenburgh to the U.S. Attorney's office requesting the return of materials confiscated from the

Mother Earth offices.

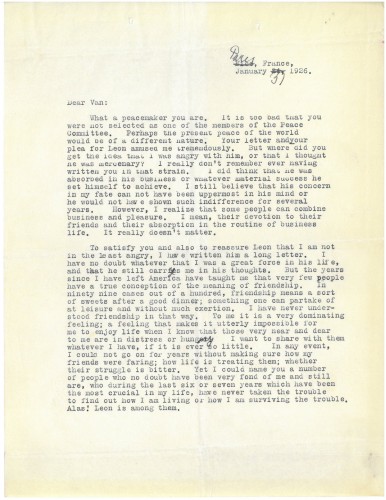

The first page of a 1926 letter from Goldman to Van Valkenburgh discussing the former's relationship with Leon Malmed (aka Leon Bass), a fellow anarchist.

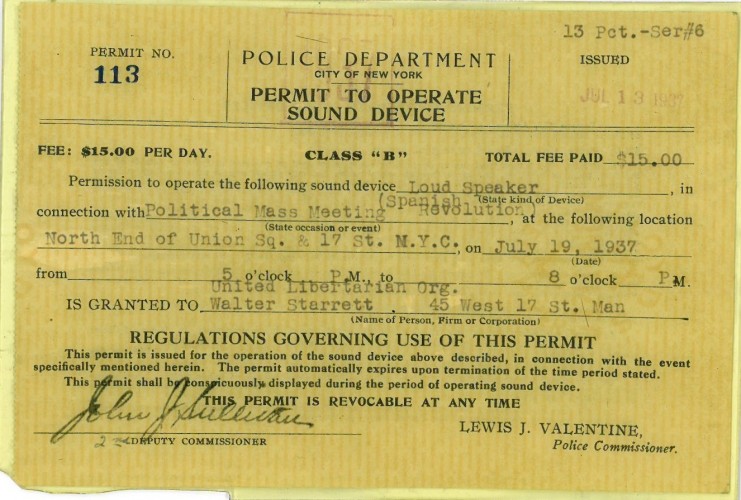

A permit obtained by Van Valkenburgh in 1937 for a political rally. His activities with the United Libertarian Organizations, an American coalition that supported the Spanish Revolution, are documented in this collection.

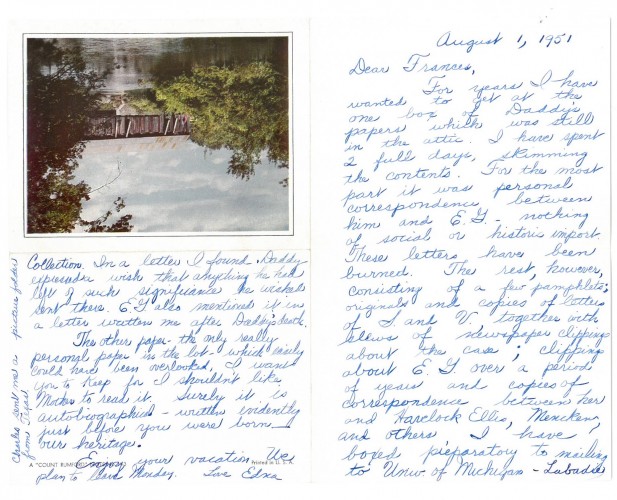

Also included in our new acquisition was this note from Van Valkenburgh's daughter Edna to her sister Frances, dated 1951, describing her work in gathering "Daddy's papers" and preparing to send them to the Labadie Collection. There are some curious references in the note that we may never understand.