Eleanor Burke Leacock (1922-1987) was a prominent Marxist-feminist cultural anthropologist active from the 1940s to the 1980s. She is particularly known for her studies of social and gender relations among the Montagnais-Naskapi (Innu) of Canada, her contributions to feminist theory, and her analyses of racism in American education. Leacock’s papers extensively document her research, teaching, and professional life. A smaller amount of material relates to her personal life and family, including her father Kenneth Burke, an influential literary theorist; her first husband, filmmaker Richard Leacock; and her second husband James Haughton, founder of Fight Back (originally the Harlem Unemployment Center). Leacock's Papers have been partially processed and an unpublished finding aid is available on request.

Growing up in New York’s Greenwich Village neighborhood within a social circle of artists, writers, and political radicals, Eleanor Leacock’s childhood was unusually free from gender stereotypes of the time. When one of her anthropology professors at Radcliffe College told his female students that “if they wanted to be anthropologists, they had better have independent means, because they would never get a job in anthropology,” she recalled thinking smugly, “I’ll show you!” for she firmly believed that demonstrating her intellectual capabilities would be enough to earn employment and respect. Leacock did, indeed, go on to make significant ethnographic and theoretical contributions to anthropology and earn a living doing so, but it was not a short or easy road.

When Eleanor transferred to Barnard College after marrying Richard Leacock in 1942, she again ran up against the limits of being female in mid-century academia. Despite receiving the only A in her drafting course at Columbia, she was denied an assistantship the next semester, because the faculty member in question refused to hire women. His only explanation was the trailing-off phrase, “You know how women are...” In an unpublished autobiography in the collection file, Leacock remembers her reaction:

Utterly stunned, I walked down Broadway with a frie[n]d, repeating over and over to him, “Do you realize there are some things I will not be able to do simply because I am a woman? Do you realize…” I could not stop recounting the incident. Eventually, however, I decided it had one important virtue: it made absolutely clear that discrimination, not ability, was at issue for a woman. To prove oneself was necessary, but not sufficient.

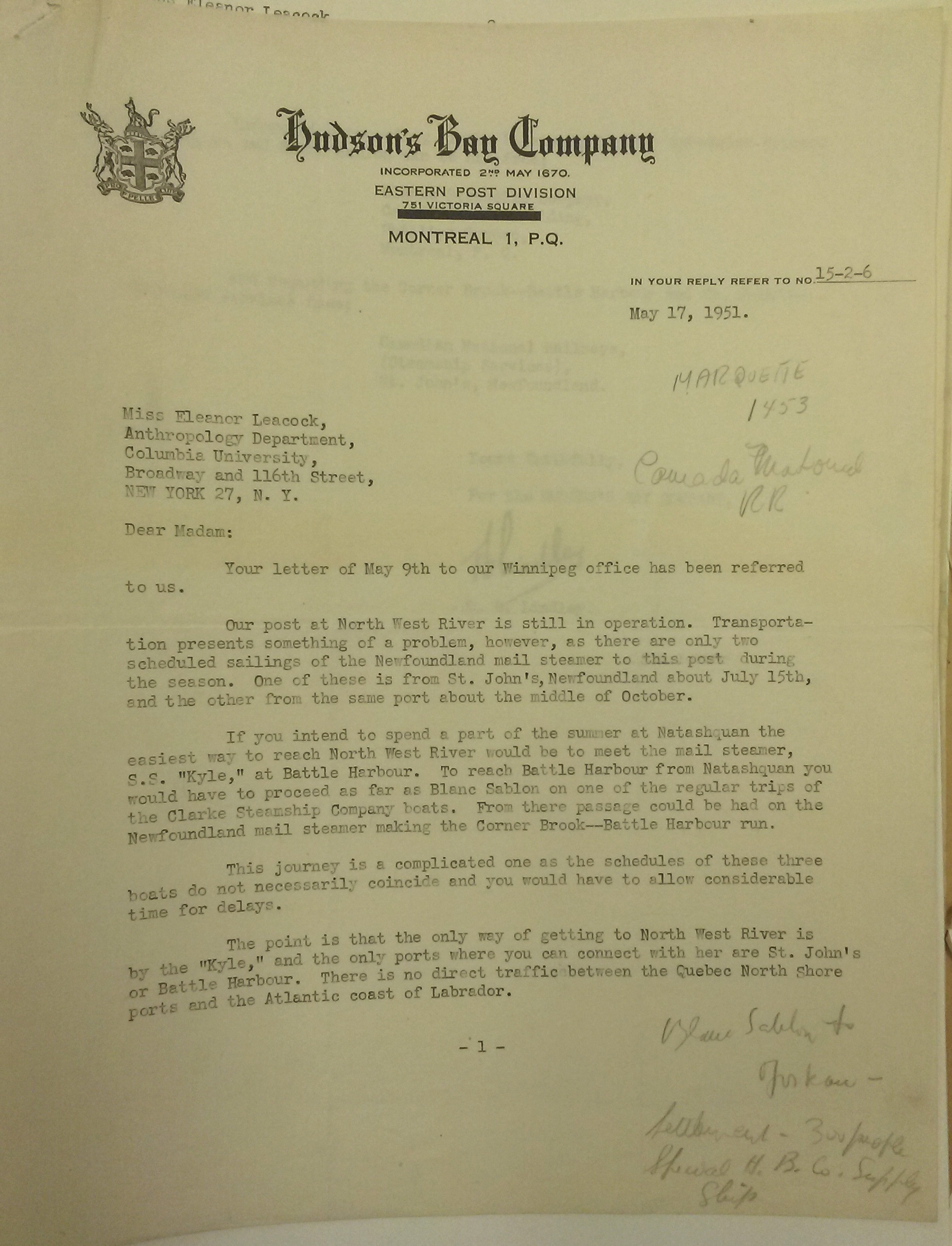

Letter providing Eleanor Leacock with travel directions to her fieldwork site. May 17, 1951. From the Eleanor Burke Leacock Papers. Studies Series. Box 3.

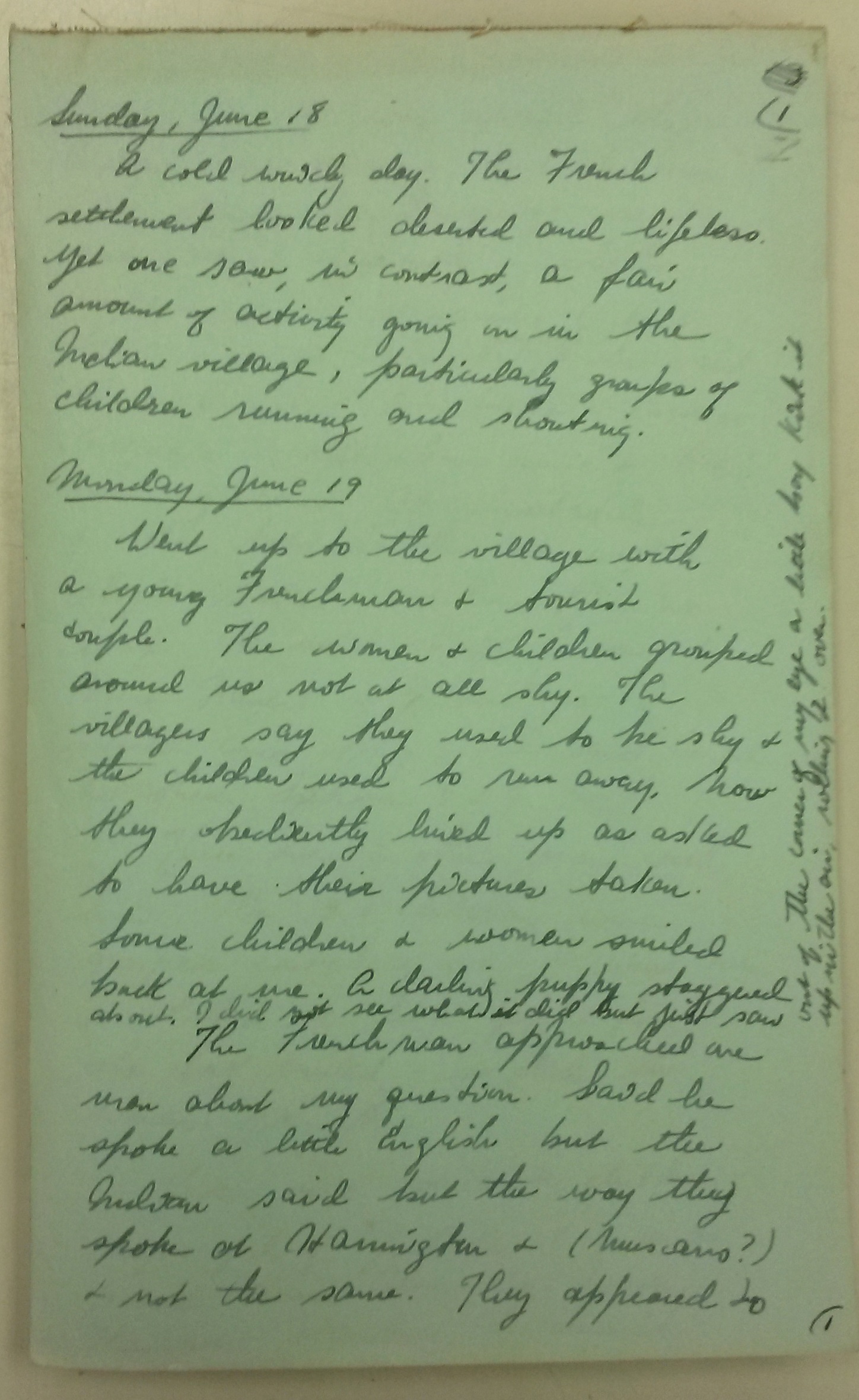

In the late 1940s, Eleanor accompanied Richard Leacock to Europe, where he was shooting films on human geography. At this time, she began archival research in Paris on social changes relating to the fur trade among the Montagnais-Naskapi (Innu) people . In 1951, she received a departmental grant to conduct fieldwork in Labrador, which she did while accompanied by her one-year-old son. Leacock’s ethnohistorical study challenged the thesis that private property was universal. Her obituary in Anthropology Newsletter later described this study as “pathbreaking in its analysis of the impact of commodity production on an egalitarian society.” The Studies series of her papers include field notes, annotated and coded maps, charts of kinship groups, note cards, and correspondence from Leacock's Labrador research.

Observations from Labrador fieldwork, 1951. From the Eleanor Burke Leacock Papers. Studies Series. Unnumbered Box.

Leacock received her doctorate from Columbia in 1952, but was told that her dissertation was “unpublishable,” with no reason given, and she received no assistance with job hunting. Columbia had once provided crucial support for female anthropologists - Ruth Benedict, Margaret Mead, and Zora Neale Hurston were all students of Franz Boas at Columbia in the 1920s - but this support had flagged in later decades. Being not only a female, but a wife, the mother of four children, and a politically-engaged radical, Eleanor Leacock was several steps removed from the Academy’s view of what a scholar should be.

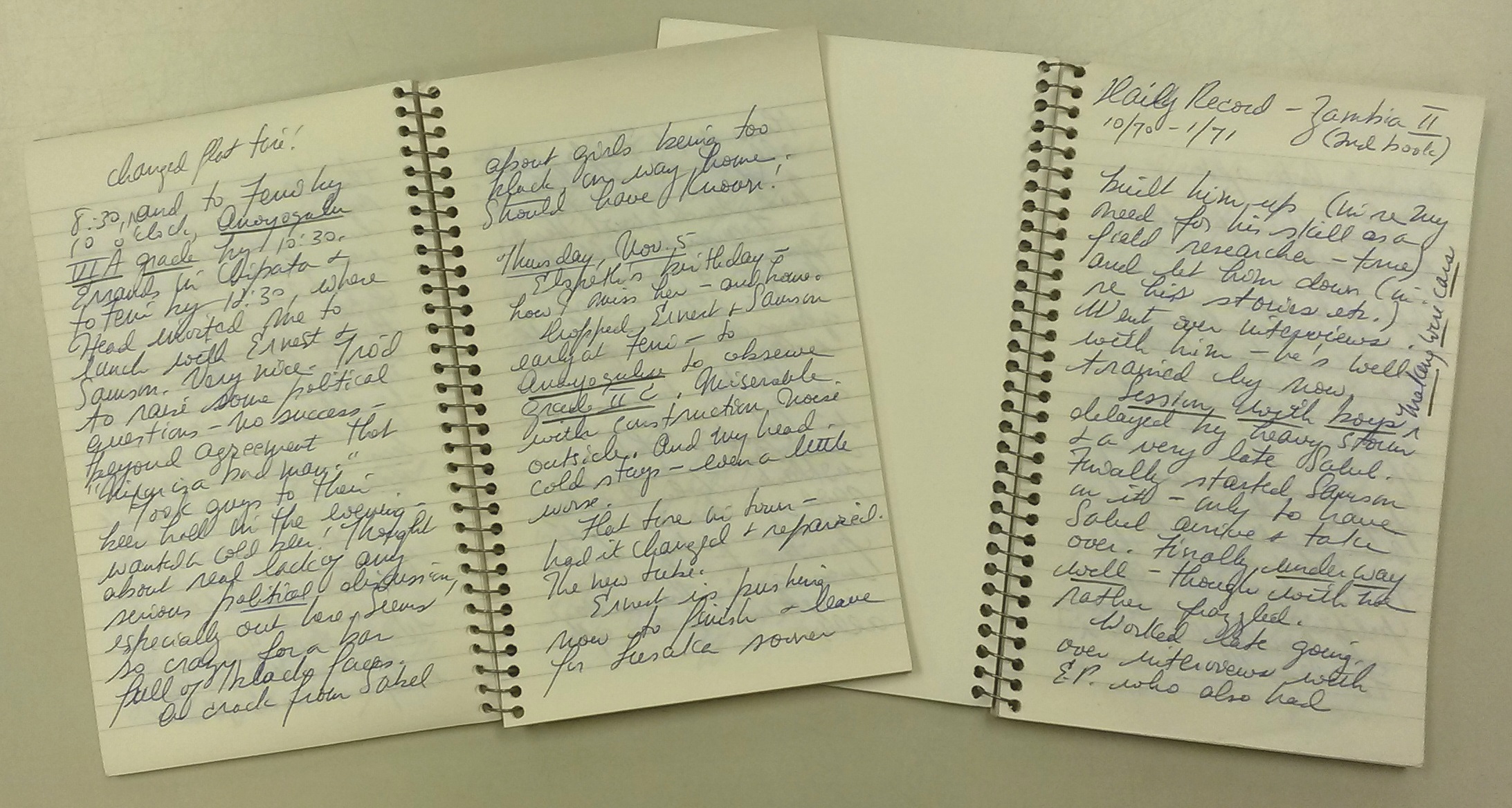

It was eleven years before Eleanor Leacock obtained her first full-time job teaching anthropology. In the intervening time she worked for a variety of research and education projects, while continuing to write, publish, and speak as an anthropologist. Her work at the Bank Street College of Education Schools and Mental Health Project informed her research and writing on education, with particular attention to “ways that class and racial oppression are reproduced in the classroom.” Her research in this area is extensively documented in the Studies series, which contain field notes, administrative files, correspondence, and reports for the Classroom Processes Study, later published as Teaching and Learning in City Schools (1969). The same kinds of materials are available for her research on decolonization efforts in primary school education in Zambia, which was closely modeled on the New York study. These are of particular interest because her fieldwork was conducted in 1970-1971, at a time when relatively few anthropologists were allowed into Zambia, due to perceived colonialist attitudes.

Observations from Zambia fieldwork, 1970-1971. From the Eleanor Burke Leacock Papers. Studies Series. Unnumbered Box.

After a decade of part-time and guest lecturer positions, Leacock was hired in 1963 as an Associate Professor of Anthropology in the Department of Social Sciences at the Polytechnic Institute of Brooklyn. Nine years later, she became chair of the anthropology department at City College, CUNY, where she remained in various capacities from 1972 until her death in 1987 due to a stroke suffered during fieldwork in Western Samoa. Papers related to her Samoan research are also present in the collection.

During the later years of her career, Leacock continued to make significant contributions to Marxist and feminist theory in anthropology, publishing more than eighty articles and reviews, as well as several books. Her research and writing process is documented in the Articles series of her papers, wherein background materials, relevant correspondence, and drafts are organized by article. At a practical level, Leacock was also known for her support of junior anthropologists, especially those marginally employed, and for her efforts to ensure that women and students from underrepresented backgrounds received the encouragement and financial support necessary to continue their studies. In the closing pages of her unpublished autobiography, Eleanor Leacock muses on both the challenges and the joys of her career:

The major theme I have dwelt on in these pages has been the overcoming of difficulties for a woman who is also radical and mother and “making it” into the higher echelons of the profession. I felt this to be the theme of greatest interest for both young women and men today. Yet my emphasis lends itself to distortion by letting it appear that thus “making it” has been my central concern. Instead my work itself has always been more important. In fact my self-image is more that of a writer than of an academic. I might even credit much of my success to the fact that I love writing - with all of its difficulties - in and of itself.

Bibliography:

Leacock, Eleanor Burke. Being an Anthropologist [Unpublished Autobiography]. Collection File. University of Michigan Special Collections Library.

Lessinger, Hanna. "A Scholar Who Never Lost Sight of a Socialist Future" [Photocopied newspaper article in Collection File on Leacock's life and legacy. Possibly from The Guardian, ca. 1987].

"Eleanor Burke Leacock" [Obituary]. Anthropology Newsletter, May 1967.

Ward Gailey, Christine. Biographical Note [Draft]. Collection File. University of Michigan Special Collections Library.