Over the course of the eighteenth century, the time and content of meals gradually shifted. By the turn of the 19th century, dinner had become detached from its earlier noontime association and might be eaten anytime from mid-afternoon to as late as six or seven o’clock in the evening, depending on the household. However, lunch had not yet become a commonly established sit-down meal. Dr. Johnson’s Dictionary of 1755 defines “lunch” or “luncheon” as “as much food as one’s hand can hold,” in other words, a sort of snack that might be eaten anytime between meals.

Jane Austen does use the terms “nuncheon” (Sense and Sensibility) and “luncheon” (Pride and Prejudice) to describe mid-day meals taken at an inn, such as the “Sallad and cucumber” and “such cold meat as an inn larder normally affords” ordered by Lydia and Kitty when they come to meet Elizabeth and Jane on their return from Kent and London. However, at home and in private parties, Austen's characters serve mid-day refreshments without laying the table or referring to such comestibles as a meal. In Persuasion, Anne Elliot’s fretful and hypochondrial sister, Mary Musgrove, is at first dedicated to spending the day on the sofa, then hopes she “might be able to leave it by diner-time,” and then under Anne’s cheering influence forgets her supposed ill-health to the point of “beautifying a nosegay; then, she ate her cold meat; and then she was well enough to propose a little walk.” In Mansfield Park, Edmund’s visits to Mansfield Parsonage are accompanied by “the sandwich tray, and Dr. Grant doing the honours of it,” and in Emma, the genteely poor Bates household offers a string of visitors “sweet-cake from the beaufet” to morning visitors (arriving between 11:00am-3:00pm) on one one occasion, and apples that had been obligingly baked overnight in the ashes of the local baker on another.

Food served informally between breakfast and dinner in genteel households often consisted of cold leftovers and required minimal preparation or intervention from servants, besides bringing it to the table or tray. That being the case, it is challenging to identify recipes specific to mid-day refreshments, but the 1796 edition of Hannah Glasse’s The Art of Cookery... does offer a recipe for “a cheap seed cake,” which might have graced the beaufet of the Bates’ household, as they looked forward to the excitement of “morning” callers.

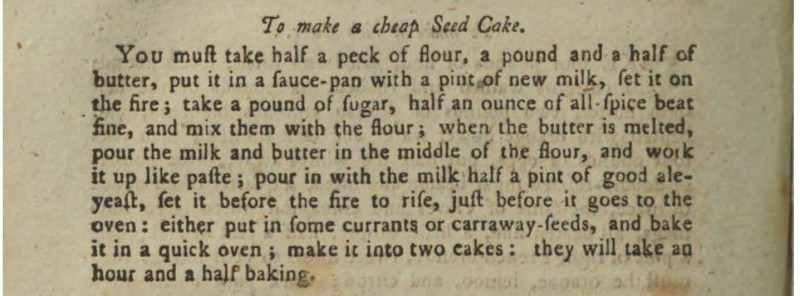

The Art of Cookery Made Plain and Easy (1796 edition) by Hannah Glasse, printed for T. Longman in London. Page 310. Janice Bluestein Longone Culinary Archive.

You must take half a peck of flour, a pound and a half of butter, put it in a sauce-pan with a pint of new milk, set it on the fire; take a pound of sugar, half an ounce of all-spice beat fine, and mix them with the flour; when the butter is melted, pour the milk and butter in the middle of the flour, and work it up like paste; pour in with the milk half a pint of good ale-yeast, set it before the fire to rise, just before it goes to the oven: either put in some currants or carraway-seeds, and bake it in a quick oven; make it into two cakes; they will take an hour and a half baking.

Notes for adventurous bakers:

- A peck of flour can actually mean a couple different amounts, but most often it refers to about 14 pounds (see The Manuscript Cookbooks Survey glossary), so this recipe would use 7 pounds. Of course, for modern households, it may be desirable to halve or even quarter the recipe before preparing it!

- Read the entire recipe carefully a couple of times in order to establish how the ingredients are used, as it is not always immediately obvious. For example, an initial read of the first few clauses seems to suggest that the flour goes into the saucepan with teh butter and new milk, but later steps clarify that the butter and milk are warmed in a saucepan over the fire, while the flour, sugar, and allspice are mixed together in a bowl.

- See the recipe notes from Dining with Jane Austen I: Breakfast in Georgian England for information and a link about the use of ale-yeast or barm in baking.

- The temperature of Georgian ovens could not, of course, be as tightly controlled or predicted as our contemporary gas or electric models; instead terms like "quick," "slow," or "moderate" were used as approximations. Various sources suggest anything from 375-450 degrees fahrenheit for a "quick" oven. Given how long this recipe suggests baking the cakes (over an hour!), I would be hesitant to use the temperatures at the upper end of the "quick oven" range, but would instead aim for something closer to the 375-400 degree range (and perhaps still checking for done-ness early, depending on the size of your cake(s). If you experiment, do let us know your results in the comments!

Bibliography:

Black, Maggie and Deirdre Le Faye. The Jane Austen Cookbook (Toronto : McClelland & Stewart, 2002).

Lane, Maggie. Jane Austen and Food (London: The Hambledon Press, 1995).