Background

Informationists at the Taubman Health Sciences Library (THL) have been teaching in the Pharmaceutical Sciences (PharmD) program at the College of Pharmacy for many years (most recently two classes in the students’ second year). As the Informationist for the College of Pharmacy, I observed that many students struggled with the material we presented on advanced searching techniques. We assumed that students had basic search skills, but when students could not remember the name of a key database (e.g. Embase), I knew our instructional content needed to change.

Some Pharmacy faculty wanted their students to develop more advanced searching skills, for a number of reasons:

-

the PharmD program is a doctoral program, requiring research skills appropriate to that level of education

-

students are required to conduct literature searching for their PharmD Investigation (PDI) projects, conducted in their third through fourth years.

-

many students go on to careers in research, whether in academia or business, where developed searching skills are necessary

-

literature searching is an essential component of evidence-based practice, a central feature of contemporary pharmacy practice

Keeping these literacy goals in mind, I revised my approach to library instruction.

Revising the Curriculum

Based on my observations over the years, I believe that, as students’ use of and comfort with search engines has increased, their willingness to learn new searching techniques for article databases has decreased: they feel that they are successful in their Google searches, so they will be successful in searching article databases. Because of this and because I thought that students needed more time to learn searching skills, I proposed a new series of class sessions, using active learning techniques and a flipped classroom model. I believed the new class sessions would give the students a better way to learn and, very importantly, practice searching techniques. The key ideas that I focused on were:

-

Sessions would be scaffolded, with specific learning outcomes for each

-

Videos would be used where possible to teach information that had previously been presented in class

-

Students would work in small groups and would be encouraged to teach each other

-

Clinical scenarios would be used rather than just a simple question, to more closely parallel the information that students are given in their therapeutics classes. The questions that were typically used in sessions provided all of the information that students needed to search right in the question (Should you add Plavix to aspirin therapy for a 65-year-old patient with coronary disease?)

On the other hand, a clinical scenario would provide more information (You have a 65-year-old patient who is at risk for coronary disease. He is overweight, has hypertension, and does not regularly exercise. When you take his family history, he also mentions that his father had diabetes. Should you add Plavix to aspirin therapy to prevent heart attacks?). With this simple change in technique, students must think carefully about the scenario and decide on the best search terms to use. If students select “hypertension”, for example, in their search strategy, their results will not be relevant to this case.

Assessment

Working with the Center for Research on Learning and Teaching (CRLT), I developed a series of formative and summative assessments. This included:

-

a pretest

-

quizzes at the end of each class session to test for the acquisition of knowledge

-

in sessions 2 and 3, the first and second quizzes are repeated to test for retention of knowledge

-

a posttest, which is combined with quiz 3.

Except for the first two sessions, when a student response system (iClicker) was used, all assessment was carried out using Canvas quizzes.

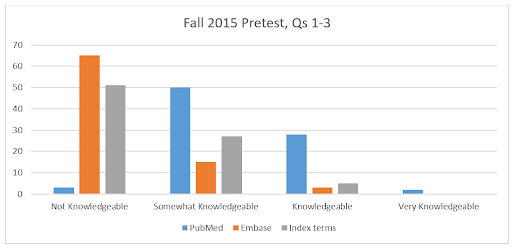

In the pretest, given in Canvas, the first set of questions asked the students to judge their knowledge of PubMed, Embase, and indexing terms, and to provide the top three resources that they use to conduct research. The final two questions tested their skills by presenting a clinical scenario and asking them to choose the best answer from a list of search strategies and filters.

In the pretest, most students ranked themselves as Knowledgeable or Somewhat Knowledgeable about PubMed, but they were much less comfortable with Embase or indexing terms (defined as MeSH, Emtree, or subject terms).

The score on the indexing terms question is often a good indication of the students’ true familiarity with PubMed, because most use the database exactly as they do a search engine, without utilizing the power of indexing terms in their search strategies.

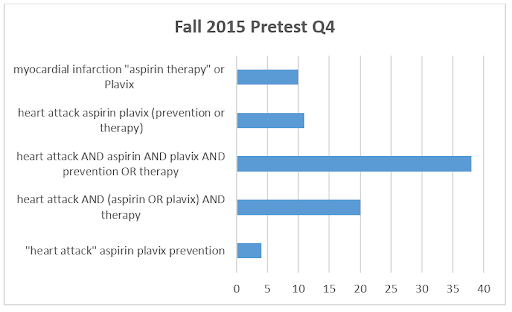

The results of answers to question 4 (below) are a good indication of the students’ true skill level. Only 20 students chose option 4, the correct answer.

Pretest Question 4: A 65-year-old patient is at risk for coronary disease. He is overweight, has hypertension, and does not regularly exercise. You are considering adding Plavix to aspirin therapy to prevent heart attacks and want to find evidence-based information. Choose the best search strategy.

Students have done well session 1: average scores for the in-class quiz over three years have been over 80% and the scores have even risen slightly when the quiz was repeated in session 2. But scores for the initial in-class quizzes in sessions 2 and 3 have been around 50%. I wondered if the class setting was making a difference to student learning, as session 2 is traditionally held in an auditorium, where small group work is more challenging, whereas sessions 1 and 3 are held in rooms more suitable for small group work.

After the second year, I decided to try a new tactic: with the help of THL colleagues Kai Donovan and Chase Masters, I created a game that each group would work together on in session 2. The game would guide the students’ work, helping them to review and to expand on what they learned in session 1, then lead them through structured searching exercises using the new techniques that had been introduced for this session. This new learning technique has been successful: student scores on the in-class quiz for session 2 have increased substantially, as have the scores for the quiz for session 3.

At the end of each year, the postests show an strong increase in student confidence in their knowledge of both databases and indexing terms.

Next Steps

Assessment has been vital in letting me know what students have learned. In the past, I have too often used the “how a class feels” metric as a measure of how much students have learned. Without an assessment, I would not have realized how little students learned in session 2 of the second year. Instead, I learned that the quiz scores were very similar, and that spurred me to create a game as another way of teaching the materials.

After I have completed a more thorough analysis my data, I will focus on the content that I am teaching and techniques that I am using, especially in sessions 2 and 3. I hope to find new ways to help increase the students’ knowledge of database searching skills, which will help in their research projects and align with the goals of the Pharmacy faculty.