Background

To help improve our current integration in the U-M School of Nursing (UMSN) undergraduate curriculum, my colleague Emily C. Ginier and I have been studying the 2015-2019 cohort of students enrolled in the traditionalBachelor of Science in Nursing (BSN) program. Using surveys, focus groups, and interviews, we are investigating students' information needs and perceptions of the library, and gathering detailed accounts of information seeking behavior and challenges. We use the data to inform our instruction, to improve selection and development of learning tools and resources, and to identify the best time for library interventions. In two blog posts, we will describe our evaluation process and findings.

Methods

At the end of every winter term, we distribute a survey, facilitate a focus group, and host individual interviews that capture participants' search intentions and behavior. The same series of data collection methods will be repeated annually with students during their program enrollment (four years). Individual follow-up interviews will be conducted with participants six months post-graduation, at the point where students will likely be working or pursuing additional education. We are interested in learning about which information skills graduates are using in their new positions, and if there are information skills that they wished the library would have covered during their undergraduate education.

Survey

Before launching our project, we piloted our brief (twelve question) Qualtrics survey with a group of second-year nursing students during the 2015 winter term. We initially reached out to our target cohort during their summer orientation in June 2015. In addition to our basic library orientation content, we also introduced our UMSN LINE project and encouraged the students to complete the survey. Participants were entered into a raffle for an incentive prize valued at $100.

The survey asked about use and perceptions of the library, resource selection, basic search skills, and information challenges. One question presented the respondent with a clinical scenario and research question, and asked about search strategy creation. We developed the following grading rubric to score those responses:

Concepts/keywords

-

Uses 1 main concept term (or alternative) - 1

-

Uses 2 main concept terms (or alternative) - 1

-

Uses 3 main concept terms (or alternative) - 1

Synonyms

-

Uses 1 synonym/concept term - 1 (x # of concept terms)

-

Uses additional synonyms - 1 (x # of concept terms)

-

Subject headings (Uses or mentions) -1

Boolean operators

-

Uses AND/OR/Not correctly - 1

-

Uses nesting correctly - 1

Search Refinement

-

Limits (Uses or mentions) - 1

-

Mentions narrowing/broadening search - 1

-

Mentions or demonstrates iterative process - 1

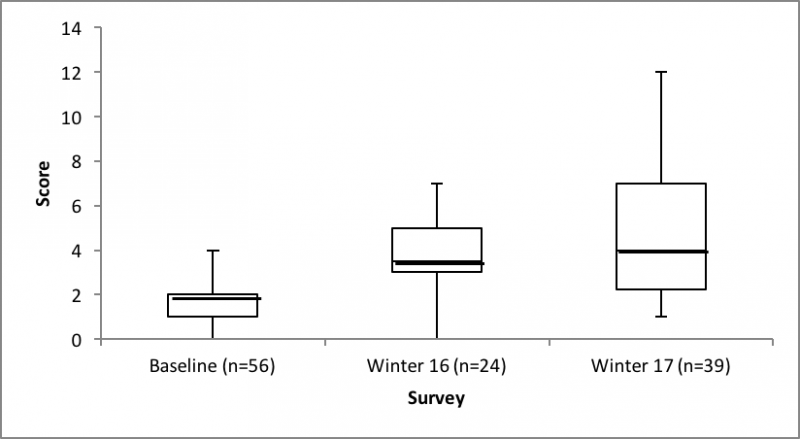

The box plot (below) presents the mean, median, maximum, and minimum scores for baseline, W16, and W17 responses.

Focus Group

Guided by some of the responses on the survey, we developed a series of focus group questions that encouraged in-depth discussion of research habits and library use, coursework and information challenges, and suggestions for improving library integration. We interviewed seven participants in 2016 and ten participants in 2017. As an incentive, we provided a meal and a gift card worth $25.

The students’ responses as to how they would begin their research process were grouped into several broad categories of resource utilization:

-

Google (or an alternative search engine)

-

a database

-

consulting a friend or librarian

-

or books in a library

One of the more sophisticated responses we heard during these converations was:

[it] “kind of depends on the type of research. Just general information I will use Google. Research scholarly articles, I will use the library database [or] if it’s like general stats or something.”

While this response demonstrated a more iterative process - differentiating between the type of sources used, based on the type of information sought after - interviewees still employed relatively unsophisticated strategies for general research.

Other general themes regarding the most challenging part of the research process confirmed responses we saw in the survey. These themes can be broadly grouped into two primary categories, that is, difficulty with sources, and an ignorance of library resources. These themes can be further broken down into:

- difficulties finding relevant and/or credible sources

- difficulty parsing information to determine which information is important

- trouble formulating searches for information

- a lack of knowledge concerning how to properly cite sources, and

- ignorance of library resources or how to access them

And finally, two more themes we identified were about the library as a space rather than resource, as illustrated by these quotes:

"I honestly thought that libraries were there to have books and where people went to do stuff. I didn't think that librarians could have helped a lot."

and

"...I assume it's going to be difficult to get in contact with the librarian and I don't know where you guys are during the day or where I could go to get in person help.”

In our second blog post, we discuss our remaining project research methodologies and findings.

If you have questions about this project, please contact Kate Saylor and Emily C. Ginier.