In 2009, U-M Library’s Preservation and Conservation department teamed up with the Digital Conversion Unit (DCU) to start digital preservation of the library’s aging audio collections. After two pilot projects, we formed the Audio/Moving Image (A/MI) Team and have preserved an estimated 1,100 materials digitally, creating 3 TB of digitized audio data backed up on servers. But there’s so much left to do.

What’s the rush?

Audio collections (and also moving image collections; that’s a post for another day) are in immediate danger of being lost. It’s not just a problem of intentional or accidental destruction -- for example, in a recent presentation to the U-M Institute of the Humanities, Josh Shepperd, director of the Library of Congress’s National Radio Preservation Program, stated that almost all US public radio broadcasts from the 20th century (recorded on magnetic media) have been lost or destroyed -- but also through material degradation.

Magnetic media (e.g. audio cassettes, reel-to-reel tapes) is decaying on the shelves. Almost all of it is cheaply made commercial stock which has, as noted in a 1995 report from the Council of Libraries and Information Resources (CLIR), a shelf life of 10-20 years. Audio tapes made in the 1970s and 1980s are well past their prime. To boot, equipment manufacturers stop producing legacy recording and playback equipment (a tangential example came up recently with the end of CRT monitor manufacturing and the ripples that’s sending through the classic arcade game restoration community). Users are left to scour flea markets and garage sales for spare machines. Technical experts leave the field or retire, taking their knowledge of how best to use the equipment with them.

Whether the Library purchased commercially published audio or was given bootleg/field recordings by amateur historians, we’re in danger of losing unique, primary source content forever. Fortunately digital preservation gives us another option. Thanks to a mature set of international standards and reliable, cost-efficient server-based storage, digital preservation lets us transfer the audio content away from magnetic media and store it as reliably as we can.

Here’s what we’re gonna do…

A reel of 1/4" audio tape from Special Collections

This is how we’re tackling the problem:

100% vended: We’re sending all of our work to audio digitization vendors. We decided against building an inhouse audio digitization lab, because it would take time and resources we can’t afford. It’s far more expedient to send our collections to vendors who already have the equipment and expertise.

Homegrown metadata: We’re capturing technical and administrative details about the digitization process in a customized Metadata Encoding & Transmission Standard (METS) schema. It’s based on the Audio Engineering Society (AES)’s schema, tailored to our workflow. We also work with the Collections division and the Technical Services department to create records so the digitized collections are noted in Mirlyn (our U-M Library catalog).

Broadcast WAV: We’re saving the data in the Broadcast WAV format (BWF or WAV), well described here. The audio preservation community – including the European Broadcast Union, which sets digitization standards for the entirety of the EU – favors use of uncompressed Broadcast WAV files. WAVs are considered the longest lasting, easiest-to-migrate audio file format currently available. The rationale is that, regardless of what audio playback software we use now or will use in the future, that software will be able to read broadcast WAVs and convert them into the audio format du jour.

Little to no editing: Archival audio master files are meant to be direct copies of the original content on tape - pops, static, background noise and all. All we do is pare away lengthy, unnecessary silences before or after the content. Production masters may be edited in order to improve comprehension, but nothing extensive.

Storing files on servers: Frankly, no other format offers greater longevity for audio. Our files are validated before ingest and copied to servers which are being maintained and checked for file and disk integrity by Library Information Technology (LIT) and U-M Information and Technology Services (ITS) professionals.

Access copies: Currently… (mumbles) audio CDs. We know, they’re not the best format out there. However, they are the lesser of many evils. Online access is difficult. Current copyright law permits the library to digitize in-copyright recordings for purposes of preservation, but limits delivery of the digital copy for access to the bounds of the physical library building. Thus, we can serve audio CDs in reading rooms on campus without involving the U-M Library Copyright Office to work out rights for every single collection we digitize. Access CDs aren’t meant to be a lasting option, merely a temporary solution until we can work something better out. Paul Conway’s grant work (spoilers below!) holds promise for online access.

What have you done! What are you doing?!

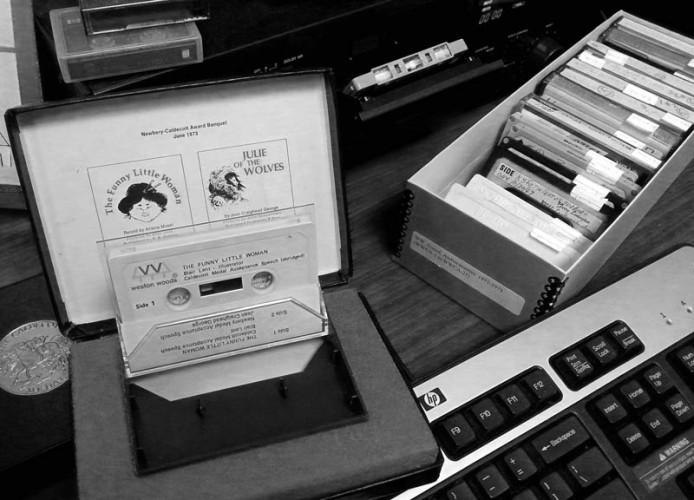

Audio cassette tapes, some in pretty cases, others loose in boxes

Before Jason Glover joined the A/MI Team in 2016, we were in pilot mode, testing out procedures, deliverables, and vendors. We worked almost exclusively with Special Collections audio materials. Why? Reasons!

- Special Collections holds unique, unpublished, and/or out-of-print audio material such as oral histories, poetry readings, and interviews. It’s almost certain no one else has this content, making them solely our responsibility to maintain.

- Special Collections has researchers chomping on the bit to access the recordings, but the staff haven’t allowed access for fear of destroying the originals during playback.

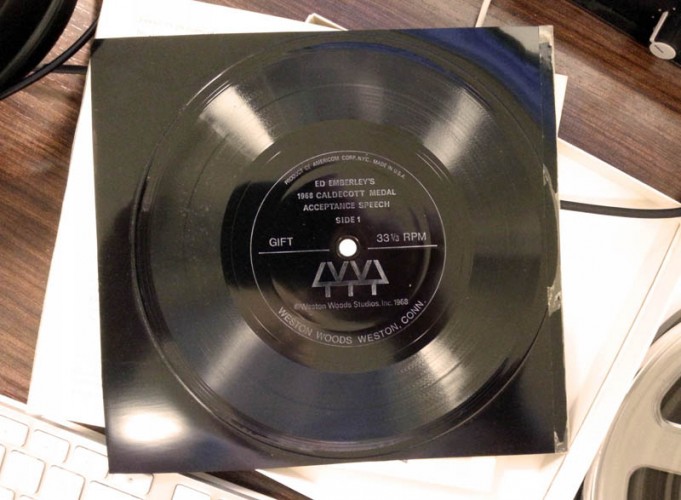

- The media types are pretty standard – audio cassettes and reel-to-reel tapes with some microcassettes and a limited amount of vinyl records.

- The media condition is decent. Aside from some cassettes that had Sticky Shed Syndrome or mold, the rest can be digitized without treatment.

Now that Jason is with us, he’s been getting our audio digitization up to sustainable levels of production. He just completed review of the Michael Kozura collection (100 cassettes), is awaiting the return of the Black American Music Symposium (30 cassettes with challenging recording techniques), and will be processing the Richard Wilson-Orson Welles Papers (138 reel-to-reel tapes and audio cassettes).

This semester, the A/MI Team is surveying the rest of the Library for other audio (and moving image) collections. It’s scope creep, but the kind you want with successful projects. Scott Kirycki, a School of Information grad student, is helping us with the survey through the summer. From there, the A/MI team will start prioritizing digitization across the entire Library.

Finally, we’re updating our audio digitization Request for Proposal (RFP) for the fall. The METS schema needs to reflect changes in the AES standard and changes in our own practices. No doubt vendors have changes to their services and costs that we should nail down.

Is there anybody (else) out there?

A plastic record, previously bound in a magazine

We’re hardly the only game on campus. While we’ve focused on Special Collections, others have gone after other legacy audio across campus:

- The Library’s Deep Blue Documents digital repository accepts digitized and born-digital audio recordings from U-M faculty and students. The digitization specs are left up to the content creator, but Deep Blue provides the same level of secure storage that the A/MI team is using.

- The Bentley Historical Library developed their own A/MI digitization program for their collections, which is headed by Melissa Hernández Durán, Assistant Archivist for Audio Visual Curation. More information about their work can be found at the Bentley site.

- Professor Paul Conway from the School of Information is in the middle of a 2-year grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities. The aim of the grant is to provide digital preservation and online access for the Voice of America’s Music Time in Africa, a radio program started by Leo Sarkisian in 1965. Digitization of over 900 programs is almost complete and UMSI students have been creating metadata for the programs and transcriptions. This summer, the project will explore creative solutions to provide access to this copyrighted material, testing 30 programs on the MiVideo streaming service. More information about the Music Time in Africa grant can be found at the project site.

If you have questions about our project, check out the AMI Digitization site. Also, feel free to email the team for more information (LibAMITeam@umich.edu)!

All photos provided by the author.