What is Digital Content & Collections at U-M?

Digital Content & Collections is a part of the U-M Library! One of the main services of our department is to build and maintain digital collections for the University and community. To define - a digital collection provides long-term access & discovery, with a visual presentation, of our collected and curated physical material. This physical material has been digitized and is considered useful from a scholarly or research standpoint, and worthwhile to put online as a digital corpus.

We are always working to improve our digital collections service. Recently we implemented a new application for our finding aids that allows users to discover archival materials across multiple repositories at U-M Library, the university and across the state. We also developed better user interfaces for our text and image digital collections - bringing them into the modern world - and took the time to make them mobile-friendly, compliant with current accessibility standards, and easier to navigate.

In that vein of improvement, DCC was excited to be able to hire two interns – Latitude Brown and Andy Nakamura – from January-September 2025 to help us with improving descriptive metadata in some of our digital collections – in particular, those that describe potentially objectionable or harmful content. This blog post is about their experiences and the projects they worked on!

What is metadata, and why is “metadata remediation” important?

Metadata refers to descriptive information about a given resource in the library’s catalog. Broadly, metadata has a variety of purposes, from enabling a particular work to appear in a patron’s catalog search to conducting rights assessments. Thorough metadata created through meticulous cataloging is essential to the service of the library, but doing so is rarely quick or easy. Creating metadata requires substantial human labor that is in limited quantity and must also be allocated across different projects/tasks. Metadata remediation is a way for us to go back and dedicate our attention to collections so that we can better connect library patrons with the full breadth of our institution’s resources.

We met with partners from the William L. Clements Library and the Bentley Historical Library, who shared several harmful content remediation projects that required our attention, so the goals of the internship expanded from metadata remediation to include content remediation. Similar to metadata concerns, it can be difficult to identify item-level sensitive content issues because of the amount of content in these collections, and because many of these collection materials were created decades ago, there is a substantial amount of harmful content still housed within them. Harmful content remediation is important because when these issues are unchecked they become barriers to safe, open, and equitable access to information. Our approach to remediation preserves the integrity of the collection materials while offering patrons context about objectionable content prior to engaging with it. Through our internship projects, our recommendations have already resulted in tangible actions on the ways collections are presented to our users, such as in the screenshot below.

Content warning on the home page of the Alfred Wilkinson Wilson digital collection.

Most of our projects revolved around identifying potentially harmful text or images within existing or upcoming library collections and suggesting remediation actions such as publishing a sensitive content statement on the collection page or implementing a screening mechanism to hide an image from view unless the user consents to seeing it. These contextualizations allow for users to be informed about the difficulty of the material contained within the collections, and can make collection navigation safer for patrons without needing to withhold these materials from them.

Our workflow

As is true for many online web products, what you see online is the polished result of what happens under the hood. Let’s show you how that happened for one of our projects (the project will be described more fully in the next section).

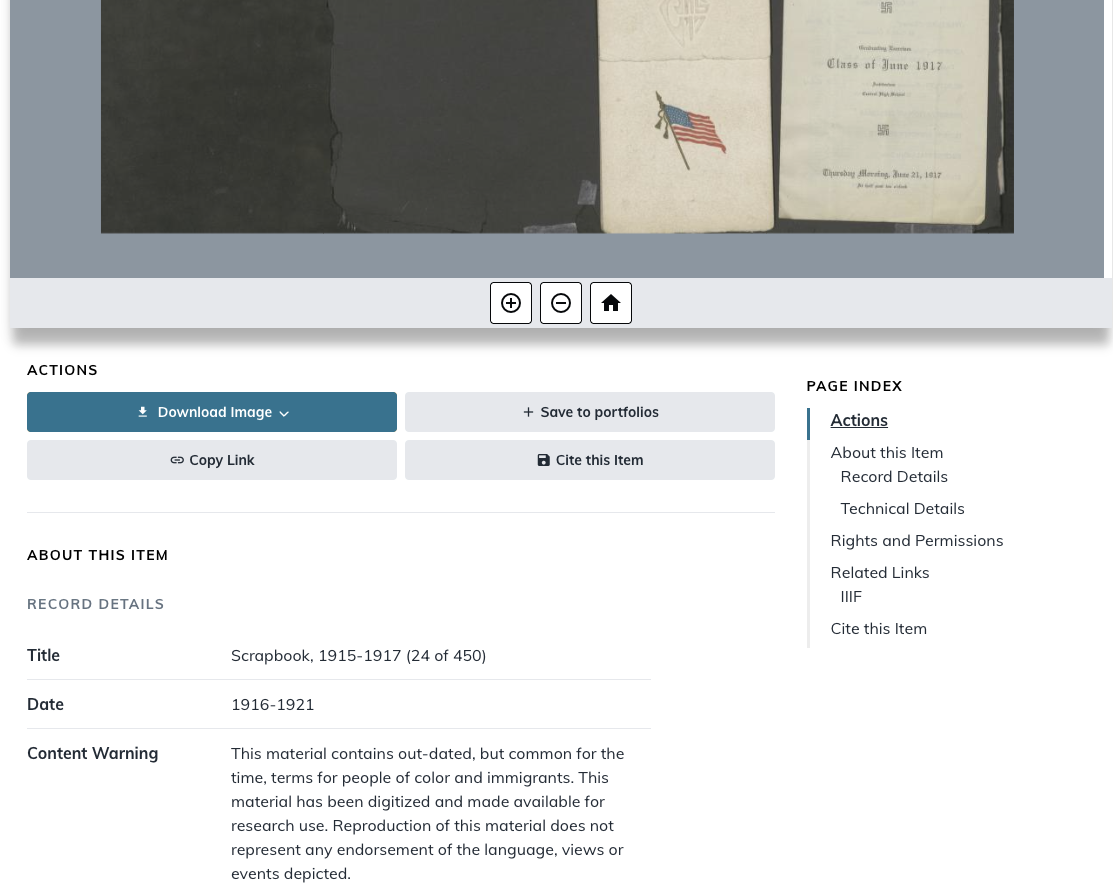

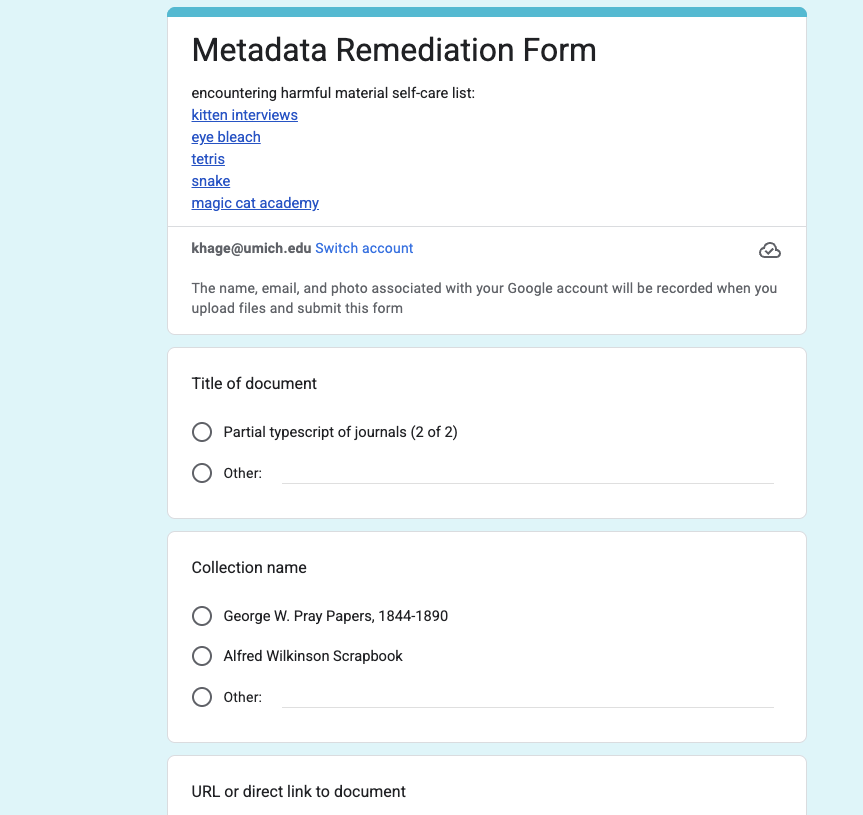

We knew that we’d be doing a fair amount of data entry, so we developed a Google Form that would make that easier.

Metadata remediation form used by interns to capture potentially objectionable content in the identified digital collections.

The helpful links at the top of the form - if looking at objectionable content became too much for our brains and emotions - are: Kitten Interviews, Eye Bleach, Tetris, Snake, and Magic Cat Academy!

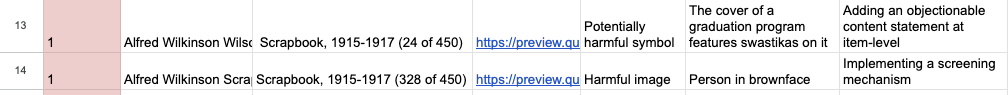

The results of the form were sent to a Google Sheet (spreadsheet).

Two rows from the resulting spreadsheet for metadata remediation work.

The above screenshot shows a cleaned-up version of the spreadsheet. We discussed each data entry and then described our intention for each one - either adding a statement about the content, or implementing a screening mechanism - consistently across the spreadsheet.

Much more behind-the-scenes work then took place through the work of our DCC image digital collections coordinator. As you might expect, we do a lot of work making metadata fit seamlessly in our systems, so that descriptive metadata is easy to discover and view in our user interfaces. And the result of all that work is that the remediations to our metadata and content are then available in our online system. Here are two improvements we added as per the spreadsheet above:

And in the case of this digital collection, the Alfred Wilkinson Wilson Scrapbook, which we had taken offline because of its problematic content, we were able to relaunch it!

The projects we worked on – what kinds of problems did we find and fix?

Alfred Wilkinson Wilson Scrapbook & George W. Pray Papers (Bentley Historical Library)

As noted, our priority was working on digital collections that had been identified as having potentially harmful or objectionable material. These two digital collections were already digitized and hosted. The Alfred Wilkinson Wilson Scrapbook collection was taken offline in 2020 after blackface images were discovered through routine review, and we didn't have the means at the time to take remediation action. The George W. Pray Papers were in production, but the Bentley informed us that some of its content could be upsetting or inappropriate. See the “Our workflow” section above for an example of how we organized the remediation efforts for these digital collections.

Latitude says:

My absolute favorite thing about working in the archives is reading diaries, because I am a diarist myself and I think it's a fantastic way to reach back into the past and see that people were not so different from us in the past. Mr. George Pray really rattled me! He was describing graphic acts in his diaries, both from his personal affairs as well as his experiences learning to be a doctor in Michigan. When I talked about him to my library colleagues, I found myself mentioning that he was kind of an icky man, but historically important for researchers; both to see the everyday life of a man of his time, but also as an important figure in Michigan, as part of the first graduating class at the University of Michigan and as one of the first physicians in Michigan. He also went to the places that I go, such as the Arboretum or Dixboro, and it was interesting to watch someone else do the same things that I do, a hundred years in the past. I wrote about it in my diary, in the future.

Andy says:

As I combed through the Wilkinson Wilson collection, I was always fascinated by the kind of haunting presence of World War I that would come into focus through oblique references in newspaper articles about football games and campus events. I got the sense that this scrapbook not only recorded a time in U-M’s history, but that it belonged to a specific time in world history, and learning about that history felt very visceral because it was captured in the pages of an otherwise fairly banal account of a person’s college experience. Though I regularly encountered harmful content, I ended up being pretty excited to read about the world through this scrapbook, which further stressed to me the importance of remediation.

As we mentioned earlier, this project was about investigating descriptive information (the existing metadata), however it quickly turned into examining individual content, as the metadata was minimal in terms of how well it described the content. An extra challenge was for items that were handwritten, as those can be difficult to read! We pivoted to investigating material that was visual or typewritten.

Result - The Wilkinson Wilson collection had been taken offline because of its problematic content. We were able to relaunch it by adding the screening mechanism and objectionable content warnings for the problematic content. We also were able to add content warnings for the Pray collection.

David V. Tinder Collection of Michigan Photography (William L. Clements Library)

The David V. Tinder Collection of Michigan Photography is an extremely large digital collection that relied on crowdsourcing volunteers to help transcribe the postcards in the digital collection. The collection was launched with those transcriptions after reviewing the materials for potentially objectionable material (it was the first digital collection launched with our screening mechanism!). After launch, we were asked by the Clements to review flagged items that needed further review, to see if they needed the screening mechanism. Our job was identifying both the metadata and image content that seemed harmful or objectionable – eg, the metadata tag “American Indians”.

Latitude says:

This project was probably the most intimidating because there was SO MUCH to go through.

Result - We recommended additional metadata and item-level remediation to the Clements staff, for many of the flagged items.

Jewish Heritage Collection (Special Collections Research Center)

The Jewish Heritage Collection was a smaller digital collection that we worked on in a similar fashion to the Tinder Postcard project – checking for material that researchers might want to be warned about.

Latitude says:

This was my favorite collection to work on, because it was digital photos of items from Jewish houses, including half-empty boxes of Hanukkah candles. This felt extremely special to me, because I felt I was seeing the contents of someone's drawers, and I have a drawer in my house that is also full of half-empty boxes of Hanukkah candles.

Result - We made recommendations to the content partner on item-level remediation for a number of items in the collection.

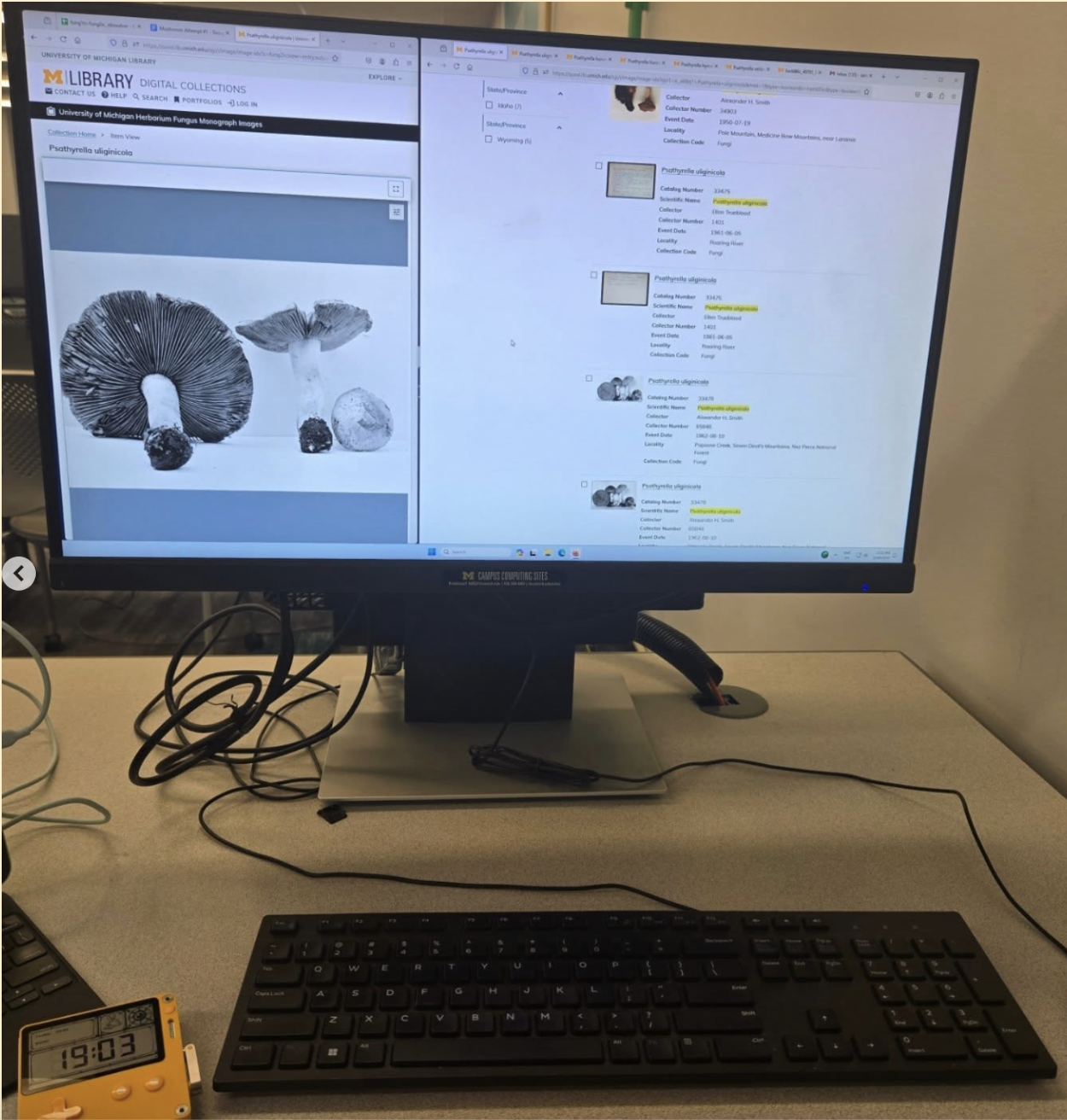

Fungus Monograph Images (University of Michigan Herbarium)

The Herbarium Fungus Monograph Images project was an effort to update older URLs so that these images could be found in the main Herbarium digital collection and the original digital collection could be sunset. This work was complicated! The picture below shows the need for multiple windows and a large monitor to take on these tasks.

Ultimately, however, we discovered – by not being able to find about ⅓ of these images in the main Herbarium digital collection – that this digital collection should not be sunset. We checked with the Herbarium team, and they confirmed this had been a miscommunication many years before. We were grateful that we were able to avoid the removal of a vital resource!

Photograph of Latitude Brown's desktop computer during the Fungus Monograph Images project, taken on June 1, 2025.

Latitude says:

My favorite programming thing is being able to use regular expressions, and regular expressions literally came up in this project! I needed to search for very specific strings of characters and replace them with different specific strings of characters, so I wrote a little script in Python to look and find with regular expressions for each mushroom / thumbnail pair.

Andy says:

This was our first project after working on the Wilson and Pray collections, and it was really interesting to learn about the decisions and behind-the-scenes work that goes into maintaining and updating digital collections!

Other Projects We Worked On

- “General Digital Collection” Dates

- We identified publication dates for currently restricted serials using on-campus, wired computers, so we could determine which volumes were in the public domain and eligible for public access.

- Result - This project opened digital access to library resources through adding missing dates.

- Bentley Image Bank

- This was similar to the Tinder Postcard project, however instead of looking at the entire Bentley image collection, we were given some potential keywords for finding objectionable content. We used those – and expanded on those when necessary – to obtain a list of items.

- Result - We recommended that Bentley staff review a number of items to see if they need objectionable content notes or the screening mechanism.

- Harper’s Weekly

- This publication was unique for being fairly progressive even though the catalog dates back to 1865. We looked at a sample of 10 pages from across 10 volumes, but we found nothing particularly problematic – likely because of its progressive nature! – so we opted to turn our attention to other projects.

- Making of America Report Titles

- We looked through the list of topics in the large collection of American western frontier reports to find any specific report titles. Those titles were added to the metadata for the specific items. (An example, under "Contents Listing".)

- Result - We helped to improve user experience in the library by identifying titles and topics that can make keyword searching through voluminous content easier. DCC gets a fair number of user requests about these reports, so this will also generate fewer feedback tickets!

Tips for anyone interested in library work, digital collections, or remediation

Ask Questions!!!!

Don't be afraid to ask questions! Reach out to other librarians, your colleagues and cohort, or folks working at different archives and libraries. It’s helpful to see what others have already done, because the chances are high that someone has faced similar challenges to you. Learning from those who came before you can help you do your best work and understand how the past influences the future. Use the “living archive” around you to solve your current problems! Remember, you can also lean on your supervisor! They have lots of experience and can offer good advice. If you're unsure about something, ask them. They've probably dealt with similar problems before and can guide you through them.

Archiving Can Be Lonely, Especially Working Alone

So don’t do it! Utilize your cohort of colleagues and the world around you - and stop working from your couch. Talk to your coworkers! Working with others means sharing ideas, resources, and support, which makes the job easier and less lonely. You can work together at a cafe, in a student lounge, or use the library for its other purpose - hanging out!

Take Breaks & Take Care of Yourself

When you’re working with digitized collections that have “icky” material, it’s really easy for that to bleed over into your “home” life, and you’re literally taking it home with you, probably, as you work remotely. Using the Pomodoro Method can help a lot – working for 25 minutes, then playing a short video game for five or seven minutes – little games like Snake or Tetris, where you’re not really getting sucked into something, you’re just chasing a high score for a couple minutes. Working at a desk or a table can also make all the difference – stop shrimping yourself on a couch! You can and should also use a real physical mouse at a table/desk – this will let you look at spreadsheets for longer periods of time without suffering so much.

Internships like this are helpful for both students and libraries. For students, they provide real-world experience and an opportunity to learn skills that can't be taught just by studying in school. For libraries, they bring new ideas, enthusiasm, and a way to meet future professionals. Everyone gains something!

Thank you's / acknowledgements section

Thank you to staff at the Bentley Historical Library - especially Gideon Goodrich and Matt Adair - at the William L. Clements Library - especially Emiko Hastings - and our staff in DCC - especially Rob McIntyre and Chris Powell - for their guidance and assistance. Thank you also to our colleagues Annika Dekker and Diana Sykes for their work on the finding aid for Tinder Postcards.

And a huge thank you to donors to our U-M Library who made all this work possible!