Background

We often look for mechanisms to create better and more robust metadata about our materials in our digital collections. The better the metadata, the easier it is for end-users to find the thing they are looking for. Or something they weren’t necessarily looking for but found as a result of that better metadata. In other words, robust metadata increases the discoverability of digital collection materials.

To that end, the Digital Collections Service partnered with Justin Schell and his team in the Shapiro Design Lab (part of Digital Scholarship and Creative Spaces) at U-M Library to use Zooniverse, a crowdsourcing platform that allows us to post existing materials for anyone to view and add descriptive information to.

Zooniverse was originally developed at Oxford University in 2007 to involve the general public in scientific research. Since that time, Zooniverse has expanded to institutions around the world, facilitating millions of users contributing to hundreds of projects. Volunteers are presented with a series of tasks, which can include tasks that involve drawing on the screen, multiple choice questions, text transcriptions, and more. Volunteers help classify images from trail cameras around the world, identify gravitational waves, transcribe ancient Greek papyri, and much more.

The Design Lab has facilitated a number of Zooniverse projects over the past 8 years. The Zooniverse projects described below all became digital collections, with other projects resulting in other digital outcomes. These include Michigan ZoomIn (which asked volunteers to identify animals photographed by trail cameras through the state), Unearthing Michigan Ecological Data (which asked volunteers to identify types of data from 100+ years of student papers from the U-M Biological Station), and Angling for Data on Michigan Fishes (which asked volunteers to transcribe a variety of fish and lake data from more than 70,000 notecards from the Institute for Fisheries Research – data from this project was deposited into Deep Blue Data in December 2024).

Improving digital collections with Zooniverse

University of Michigan Museum of Zoology, Insect Division Collection

Staff from the UMMZ Insect Division were interested in participating in the Notes From Nature Zooniverse project, which works with a variety of natural history collections around the country to, among other things, transcribe labels from museum specimens to help make collections more accessible to researchers around the world.

UMMZ staff worked with those in the Library not only to prepare images from the existing Insect Division Collection to be loaded into Zooniverse workflows (via the IIIF Image API), but also design a series of “expeditions” to transcribe date and geographic information from nearly 27,000 cricket, grasshopper, and wasp specimens held in the UMMZ collection. At the completion of the Zooniverse portion of the project, more than 1,700 volunteers from around the world contributed more than 80,000 classifications. Each specimen received three transcriptions each, and the next stage of the project was to use custom aggregation software designed by the Notes From Nature team to address disagreements amongst individual transcriptions. We then used OpenRefine to further clean the data. The final step was to create a cleaned CSV file that UMMZ staff could then use to ingest data back into their Specify database.

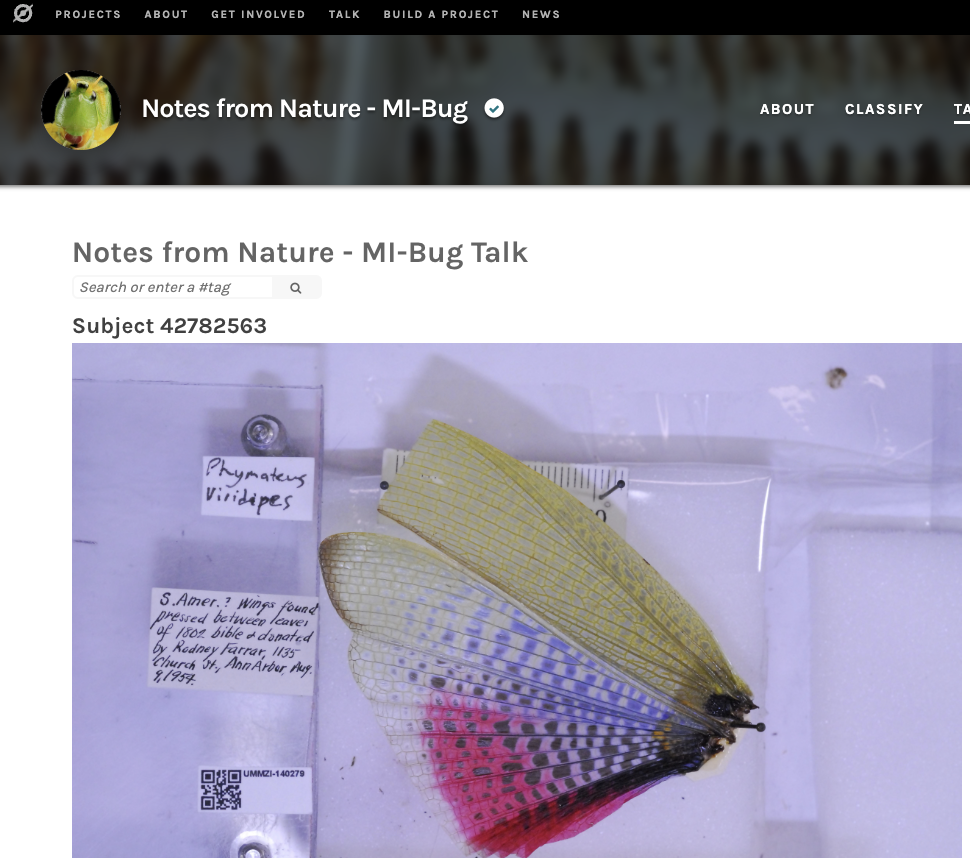

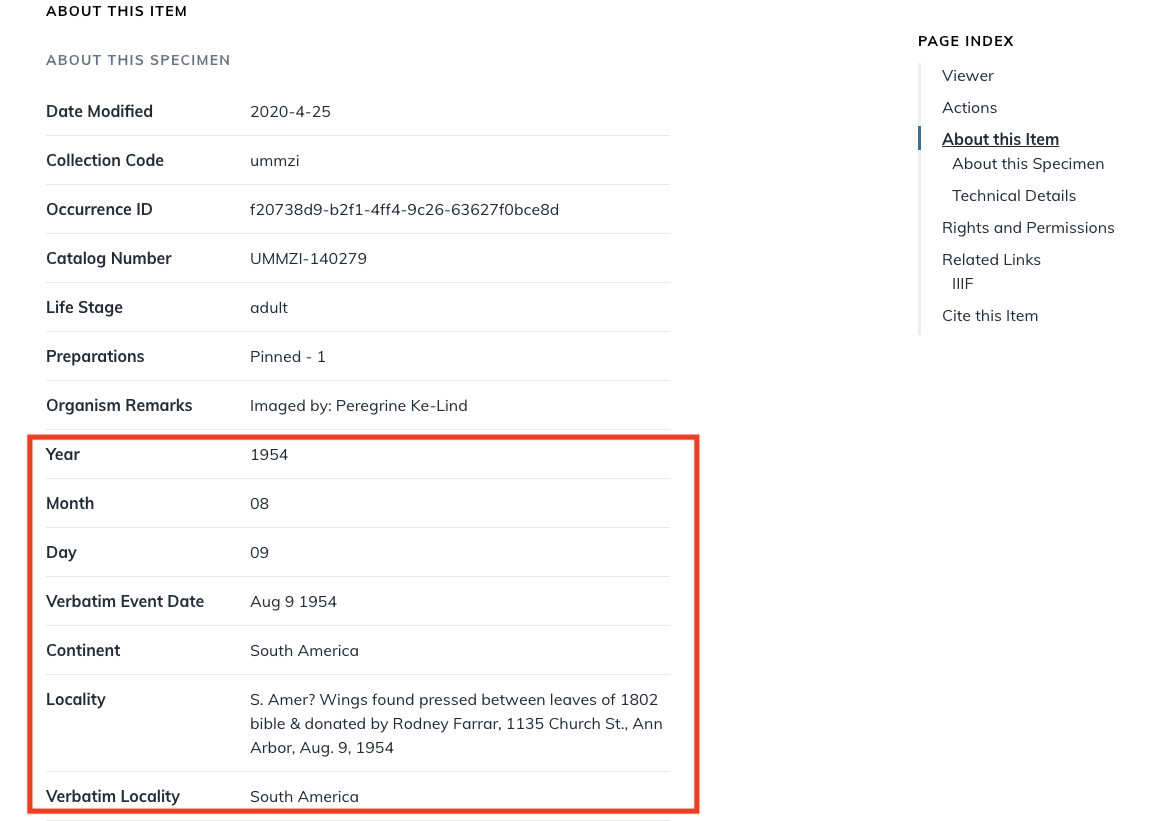

The first image is of an insect specimen from Notes from Nature from the Zooniverse platform. The second image shows a selection of metadata for that specimen in the digital collection. The red highlighted area shows the improved metadata from Zooniverse.

The UMMZ staff hired a graduate student in summer 2024 to homogenize the CSV files / spreadsheets for use by Specify. Once that work was done, Rob McIntyre, our image digital collections coordinator, processed the feed of new data from Specify into the digital collection.

War of the Worlds Fan Mail

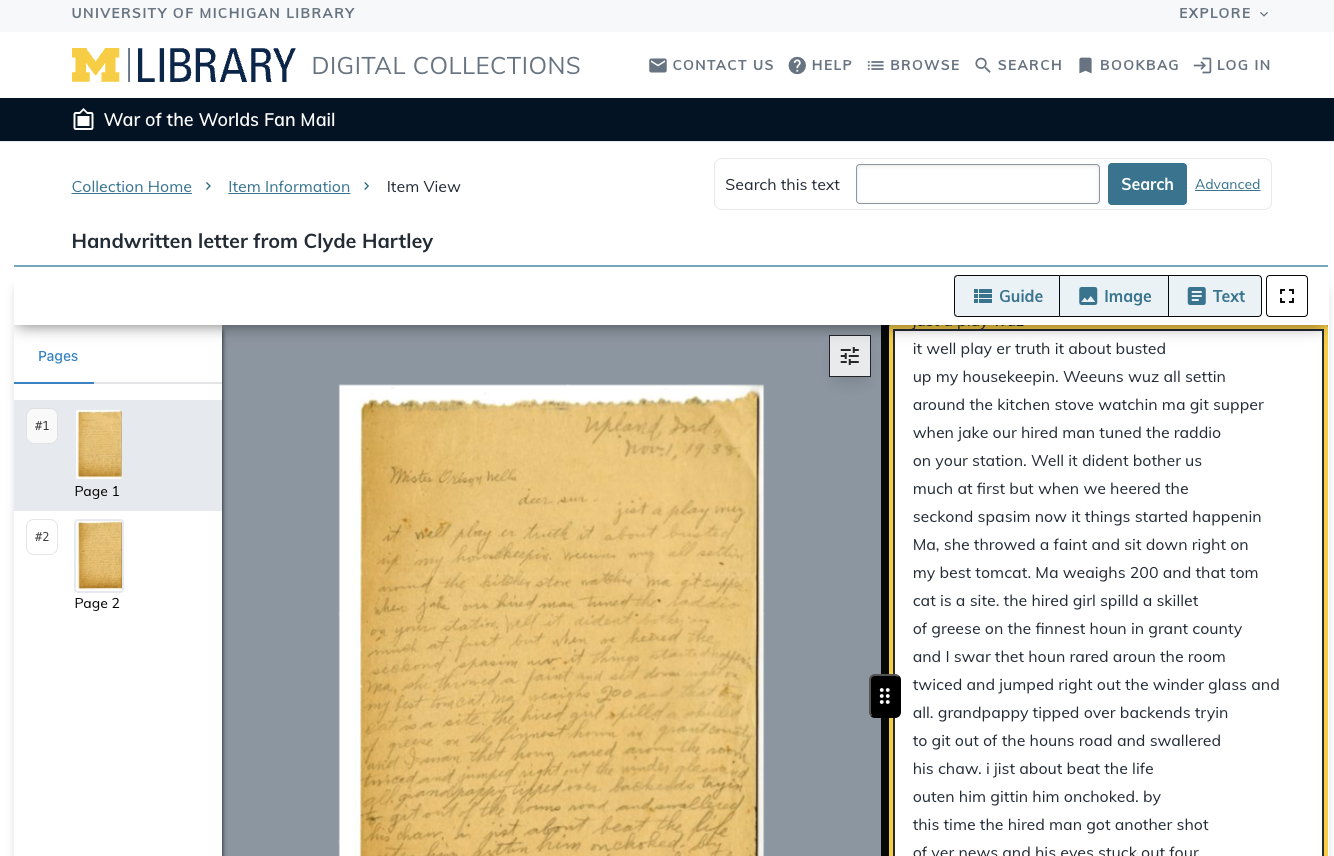

The U-M Library acquired more than 1300 letters that were sent to Orson Welles after the infamous War of the Worlds broadcast on October 30, 1938. These letters, sent from people around the country, were a mix of admiration and admonishment, with some listeners expressing anger towards Welles for playing what they felt was a dirty trick on the listening public, whereas others commended him for such dramatic and realistic storytelling through the medium of radio.

While these letters were the basis for both a book and documentary, curator Philip Hallman had the goal to make these letters public for everyone to read through a digital collection. However, this would only be possible if all of the letters were transcribed so they could be more easily read, as well as searched, by users.

Staff from the Special Collections Research Center and the Shapiro Design Lab took the scanned copies of each letter, separated them into typed and handwritten groups, split them up into single pages (if there were multiple pages to a letter), and then loaded them into a Zooniverse project called My Dear Mr. Welles. Volunteers had three tasks: first, they drew a line under each line of text in the letter. After drawing that line, a box would pop up where they could transcribe that line of text. They would then repeat this process for each line of the letter. After they had completed all of the lines on the page, they were then asked to choose from a series of options that would describe characteristics of the letter (whether the letter writer was scared, knew it wasn’t real, wanted a script sent to them, etc.).

The response to the project launch was overwhelming: all 1,300 letters were completed in approximately 36 hours, one of the fastest of any Zooniverse project. There was also incredible activity on the project’s Talk boards (discussion boards associated with each image in the project), including discussion of what specific hard-to-read words may have been in the letter and posting favorite phrases from particular letters.

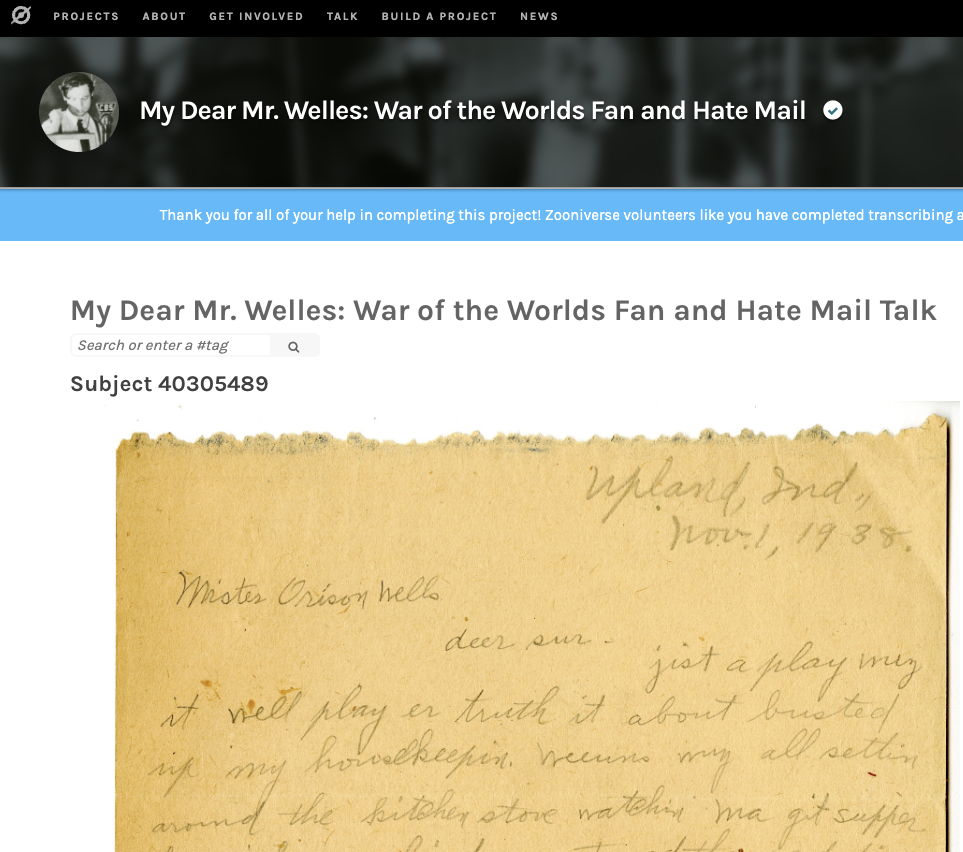

The first two images are of one letter from My Dear Mr. Welles from the Zooniverse platform and its Talk boards. The last image is the transcription and page image of the letter in the digital collection.

After the Zooniverse portion of the project was complete, the next step was to review the crowdsourced transcriptions using Zooniverse’s ALICE platform. As with most Zooniverse projects, there was significant consistency across the different volunteers who transcribed a given line. However, given that many of these letters were handwritten, and often dashed off directly after the broadcast, there was some significant disagreement amongst volunteers of what particular words might have been. Members of the project team reviewed the transcriptions of each letter in ALICE to determine the “correct” transcription for each line. And while this might seem like an argument against crowdsourcing for projects like this, such review still takes dramatically less time than transcribing such documents internally (not to mention the public engagement and excitement associated with involving volunteers into the transcription effort).

After this review of the documents, a “final” text file of the transcription was established for each letter and exported from the ALICE interface. At this point, Chris Powell, our text digital collections coordinator, put her skills to work. She used a map of identifiers to match these text files with the images and loaded both into the digital collection. It was important to double (and triple) check the images with the transcription by various means to make sure they were accurate (inconsistency in file naming can make this more difficult), so there was additional work needed by Chris to improve the accuracy.

After this checking, we launched the digital collection in October 2024, just in time for the 86th anniversary of the original broadcast!

Lessons learned

Issues we ran into doing this work were largely around the output of the crowdsourced metadata from Zooniverse and our ability to input that metadata into our digital collections platform.

We discovered that it’s important to get the file naming right! As noted above for the War of the Worlds project, not enough care had been taken to create consistent file identifiers for the images and the transcriptions, and to create these in a way that digital collections could utilize. In the future, we’ll be more careful about managing the identifier schema with representatives from digital collections.

We discovered that differences in data schemas used by our digital collection partners caused problems! The Specify tool that UMMZ uses changed how it managed relationships among items -- originally it was a one-to-one relationship, which was how the CSV files / spreadsheets were organized. The new mechanism is a many-to-one relationship, so UMMZ needed extra time and assistance to re-organize the data to make it possible to ingest into the digital collection via Specify.

Crowdsourcing via an established platform is vastly easier than building the platform ourselves; however, it still takes a lot of effort to manage the output of that crowdsourcing. Since you never know how popular a project will be, you don’t know the amount of output you’ll receive. But if you get a lot, you need to review and clean up that data yourself! It’s important to identify people and time for that to be done, before taking on a project.

Next steps

We are already collaborating on further projects! We’re working on another project with our partners from the insect specimens digital collection, asking Zooniverse volunteers to measure specific elements of bee specimens in their collection to better contribute to bee biodiversity research, especially related to declining bee populations around the world. We are also working with our partners at the William L. Clements Library on Picturing Michigan’s Past, a Zooniverse project for an upcoming digital collection of more than 60,000 postcards from the David V. Tinder collection. For each postcard, volunteers are choosing relevant descriptive metadata tags from a large list, identifying postcards that have handwritten messages on them, and then using the same method as the Welles project to transcribe these messages for inclusion into the Clements database. We hope to add Zooniverse results to these digital collections shortly.

Thank you to everyone involved in making these projects possible: Chris Powell and Rob McIntyre in the Digital Collections Service for processing the transcribed data for use in the digital collections (sometimes a lengthy task!); Philip Hallman and Vincent Longo from the War of the Worlds team; Garth Holman, Ken Eldredge and Erika Tucker from U-M LSA Museums; Samantha Blickhan from Zooniverse for her assistance with ALICE; and finally all the volunteers who did the transcriptions that have helped make these important materials available for generations to come.