This post is by Sumeyra Dursun, 2023 Heid Fellow, from her research in the Islamic Manuscripts Collection. Sumeyra is a doctoral candidate in the history of Islamic arts at Yildiz Technical University in Istanbul.

*******************************************************************************

Although the Ottoman sultans had a lot to deal with during their reign, many did not neglect to take a personal interest in different branches of art and to support the arts and artists. Sultans Ahmed III (r.1703–1730), Mahmud II (r.1808–1839), and Abdülmecid (r.1839–1861) were well-regarded calligraphers whose works on paper, tiles, and marble adorn many buildings in former Ottoman territories including the Topkapı Palace itself—the Audience Chamber, the Privy Chamber gate, and its dome.

Sultan Murad IV (r. 1623–1640) was enthroned at the age of eleven, when his uncle was overthrown. Although he is known to have commissioned an important manuscript of the Qurʾān copied by İmām Meḥmed Efendi (d.1642) and to have been presented with a masterly treatise on the arts of the book, Gülzâr-ı ṣavāb (The rosegarden of righteousness) by Nefes-zāde Seyyid İbrāhīm Efendi (d.1650). He is best remembered as the young monarch whose forces defeated the Safavid armies and conquered Yerevan (1635) and Baghdad (1638) and, not least, who prohibited the consumption of alcohol, coffee, and tobacco in the capital city. Prior to my work this summer, I was only aware of one work testifying to the fact that he also dabbled in calligraphy. To see a second work in the Islamic Manuscripts Collection at the University of Michigan Library is thus very exciting.

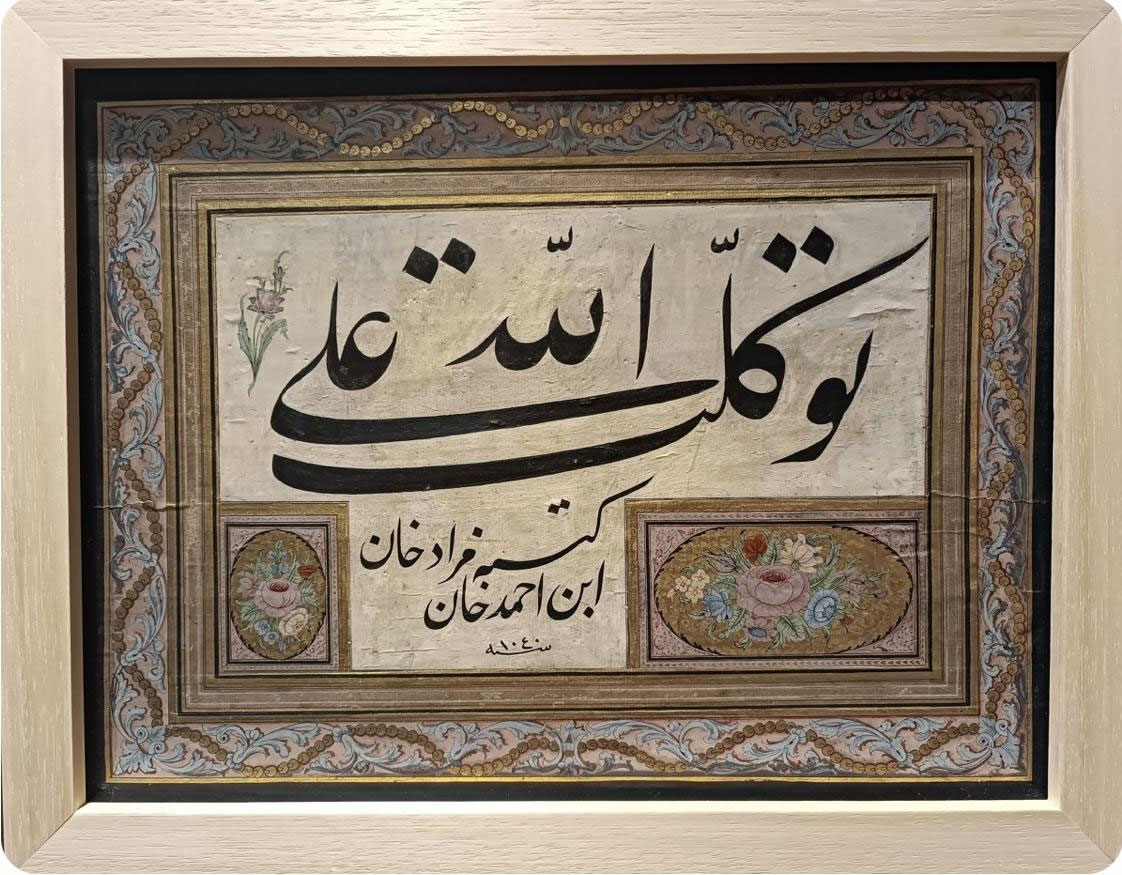

Sultan Murad IV’s only work previously known to me is written in jalī (large) taʿlīq script—the name by which nastaʿlīq script is known in Turkey (also spelled talik, celi talik). The text, “توكلت على الله” (“tawakkaltu ʿalā Allāh” I place my trust in God) is preserved at the Topkapı Palace (TSMK GY1374).

Calligraphic piece in jalī taʿlīq (celi talik) by Sultan Murad IV. (Topkapı Palace, GY1374)

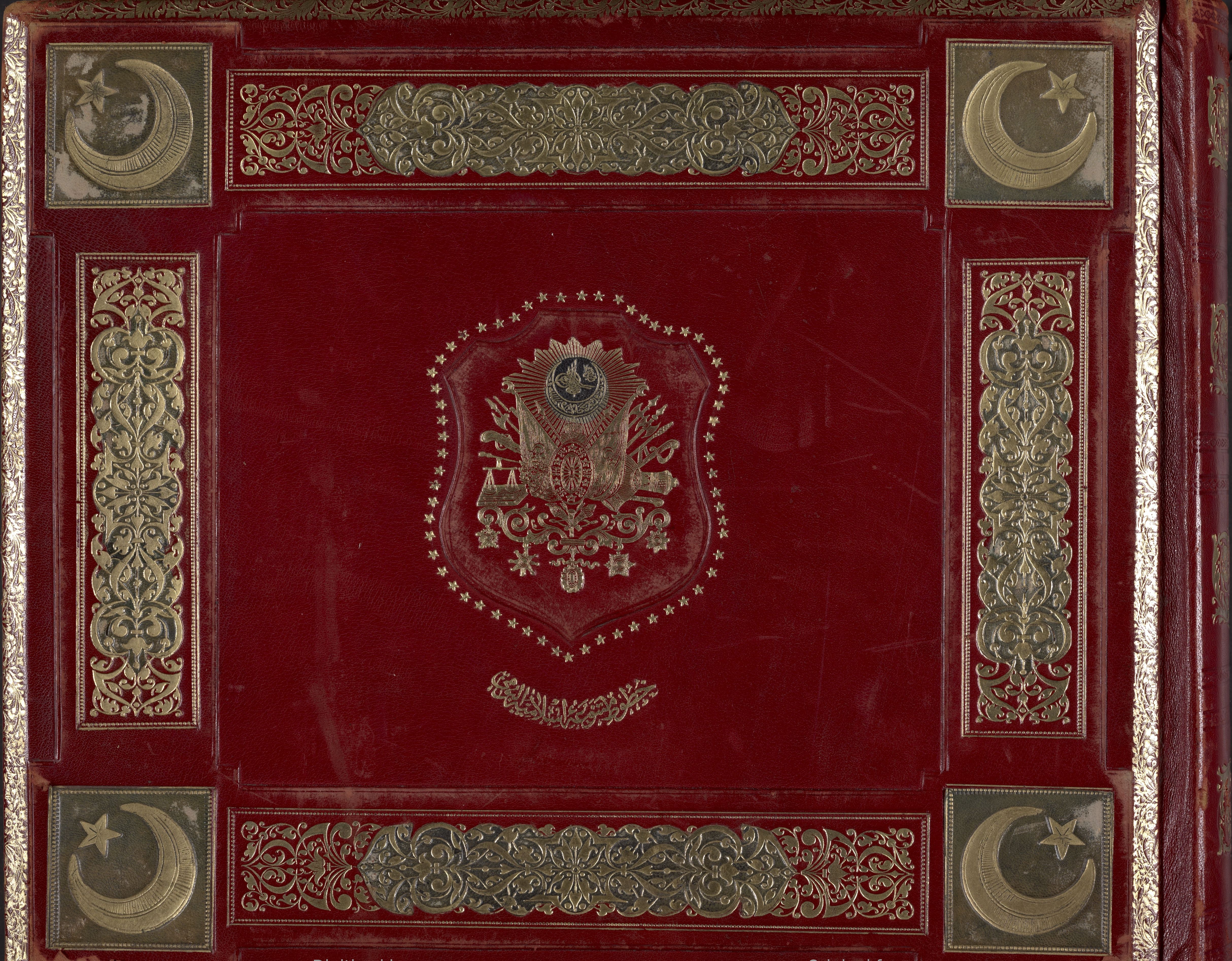

Another work by the sultan, this one in taʿlīq (talik) script, is in an album of "Islamic Miscellaneous Calligraphies" (Khuṭūṭ-ı Mütenevviʿe-i İslāmiyye خطوط متنوعۀ اسلاميه) catalogued as Isl. Ms. 441 in the Islamic Manuscripts Collection at the University of Michigan Library. This manuscript was acquired by the library in 1924 along with several hundred other manuscripts gathered in Istanbul that came to be known as the "Abdul Hamid Collection." More on that acquisition here.

Cover of the album of miscellaneous calligraphies catalogued as Isl. Ms. 441

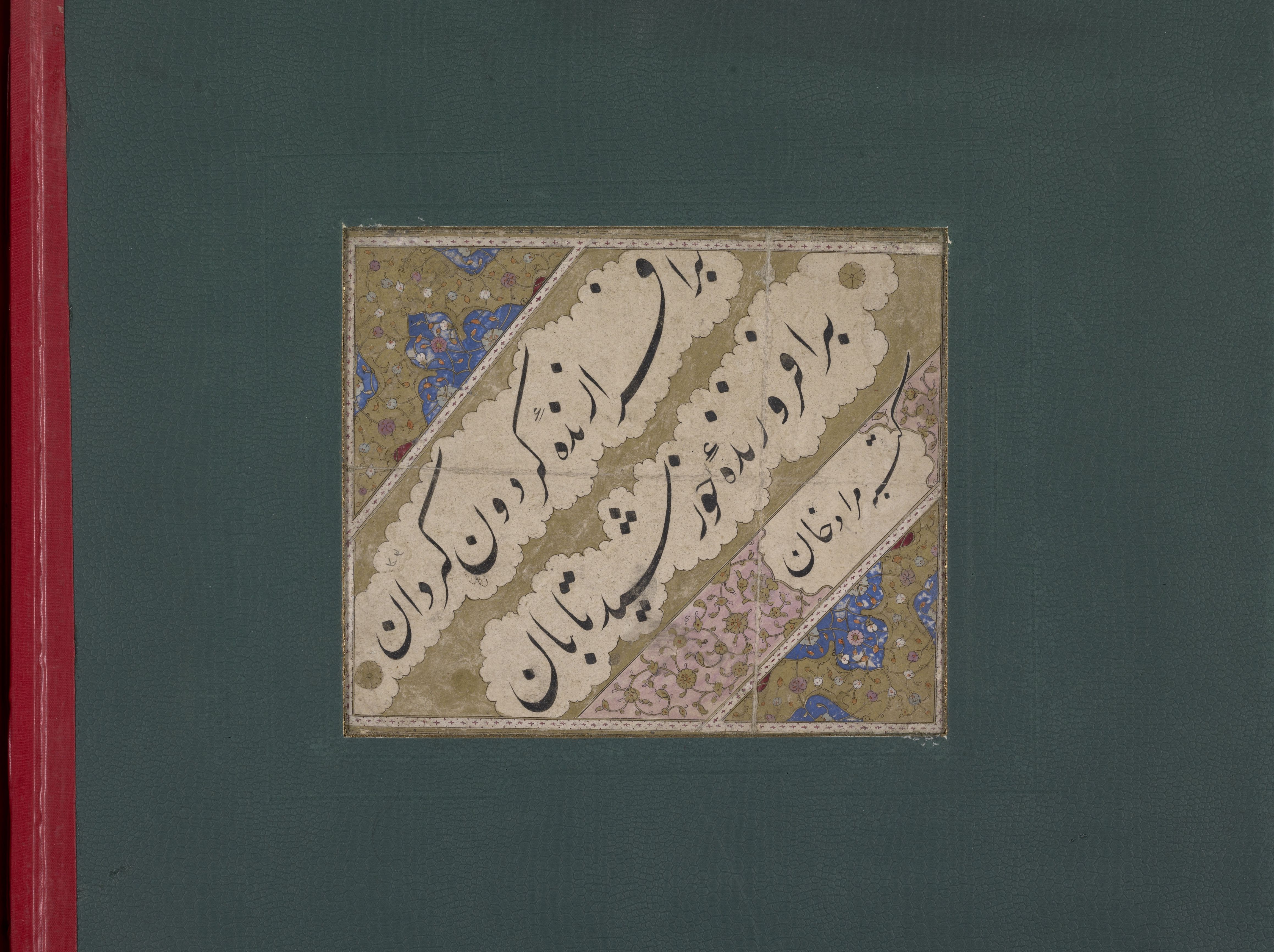

Calligraphic piece in nastaʻlīq (talik) signed by the calligrapher, most likely the Ottoman Sultan Murad IV (r.1623-1640). Fol.4b in Isl. Ms. 441, Islamic Manuscripts Collection

The piece appears on fol.4b. Its text is in Persian and reads

برافرازندۀ گردون گردان

برافروزندۀ خورشید تابان

(“Barā farāzande-ye gardūn-e gardān / Barā forūzande-ye khorshīd-e tābān” Raiser of the spinning heavens / Kindler of the shining sun)

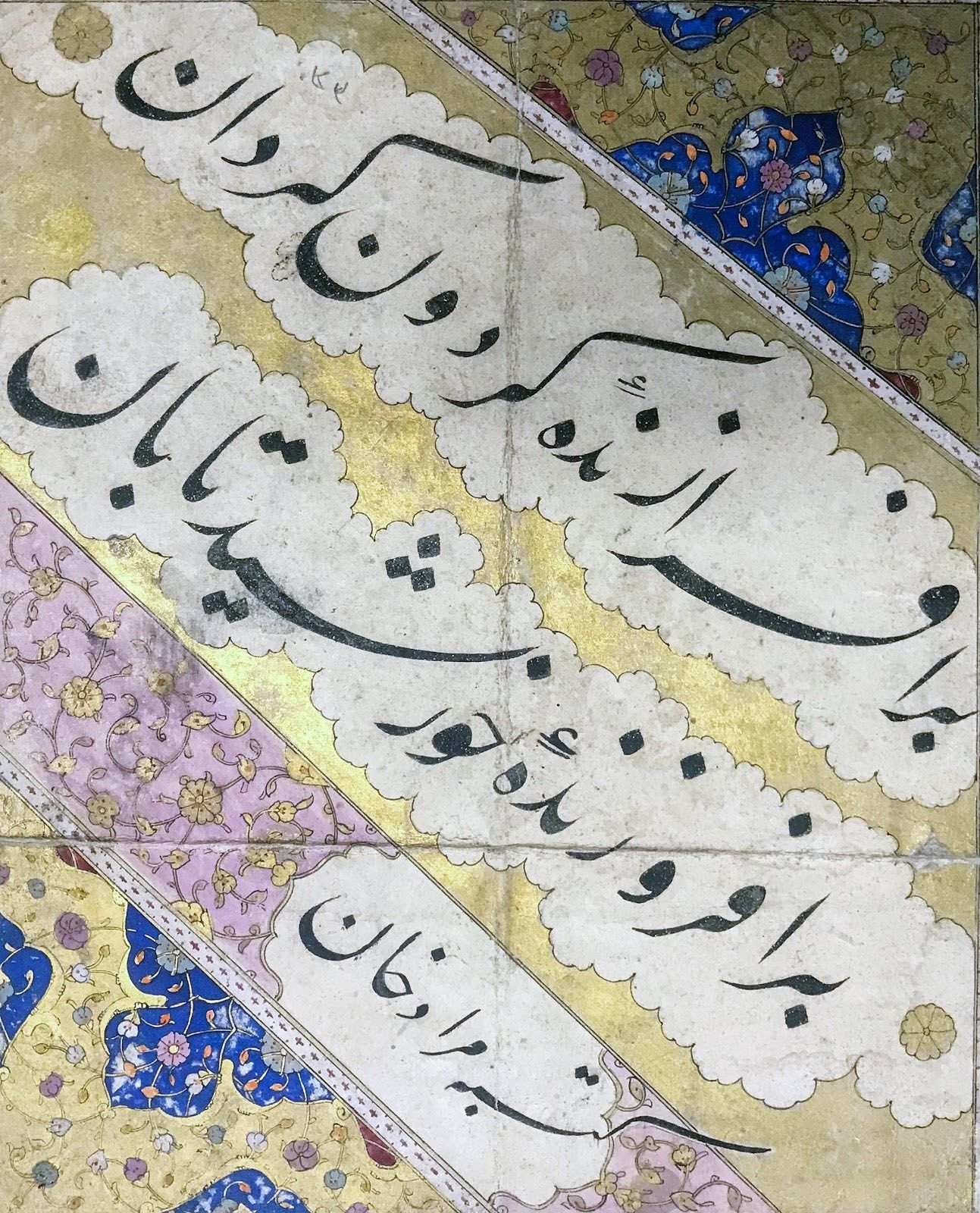

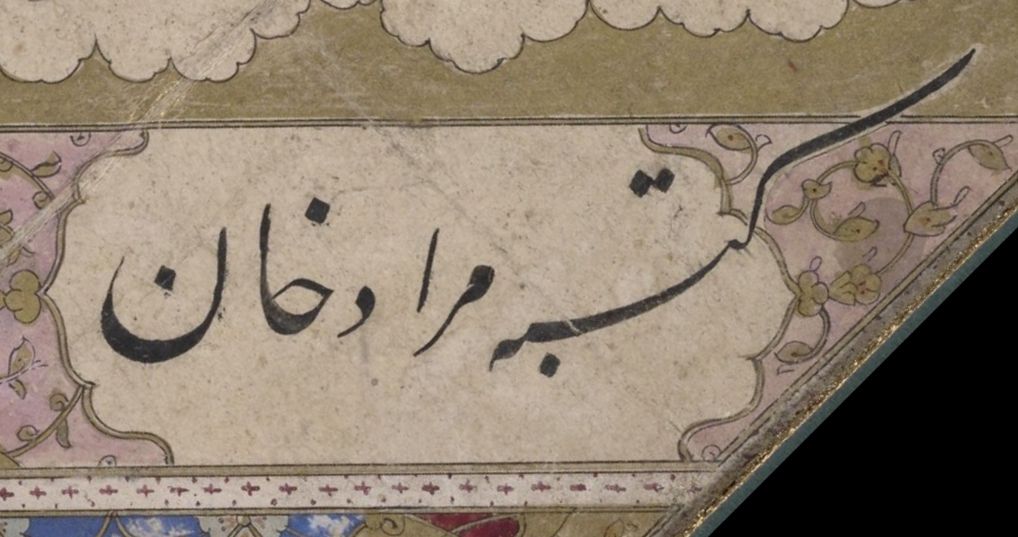

The panel is signed at the bottom as “كتبه مراد خان” (“katabahu Murād Khān” Sultan Murād wrote it).

Calligraphic piece in taʿlīq (talik) calligraphed by Sultan Murād IV (fol.4b in Isl. Ms. 441). Photograph by Sumeyra Dursun.

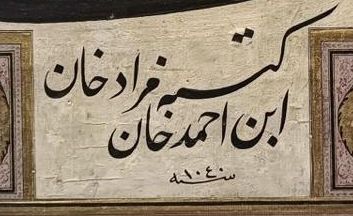

The panel at the Topkapı Palace (which happens to be on exhibit at this time) is signed “كتبه مراد خان بن أحمد خان” (“katabahu Murād Khān ibn Aḥmed Khān” Sultan Murād, son of Sultan Aḥmed, wrote it) and is dated 1040 AH (1630–1631 CE).

Signature of Sultan Murad IV in calligraphic piece at Topkapı Palace (GY1374)

The work at the Topkapı Palace suggests an approximate date for the piece at the University of Michigan Library, as well as providing authentication for it. Indeed, the fact that one of Sultan Murād IV’s only two known works is at the University of Michigan Library increases the significance of the collection there.

Signature of Sultan Murad IV in calligraphic piece on fol.4b of Isl. Ms. 441

This piece at the University of Michigan Library is written in the Persianate style of Mīr ʿImād al-Ḥasanī (d.1615) and is an important document tracing the development of Ottoman taʿlīq script in this period.

Among the calligraphers active during the reign of Sultan Murad IV, Derviş Abdi of Bukhara—one of Mīr ʿImād’s students—was a key figure in popularizing Mīr ʿImād al-Ḥasanī’s style in Istanbul. Sultan Murad IV’s works correspond to the period before Ottoman taʿlīq script reached its characteristic style. Derviş Abdi, Kātib-zāde Meḥmed Refiʿ Efendi, and Şeyhülislām Veliyyüddīn Efendi all continued to build on Mīr ʿImād’s style. Towards the end of the eighteenth century, with Yesārī Meḥmed Esʿad Efendi, the Ottoman-Turkish style of taʿlīq came into its own, and reached the present day through the works of great masters like his son Yesārī-zāde Muṣṭafā ʿİzzet Efendī and Sāmī Efendi.

While other sultans who were engaged in the art of calligraphy are generally known for works in thuluth and naskh, I think that Sultan Murādʿs works in taʿlīq, however rudimentary, constitute an important exception in this respect, and he may well have been instrumental in the decision of many of his contemporaries to choose this script.

Further Reading

Derman, M. Uğur: Türk Hat Sanatının Şaheserleri, İstanbul: Kültür Bakanlığı, 1982.

Derman, M. Uğur: Eternal Letters from the Abdul Rahman Al Oweis Collection of Islamic Calligraphy, Sharjah, trans. İrvin Cemil Schick, Sharjah: The Sharjah Museum of Islamic Civilization, 2009.