The Latin text of the Secret of Secrets as preserved in this fourteenth-century manuscript has a long and complex history. Its earliest source is an eight-century Arabic treatise entitled Kitāb ʿilm al-siyāsa fī tadbīrir aal-riyāsa (Book of the Science of Government, on the Good Ordering of Statecraft), more commonly known by its subtitle, Sirr al-asrār (Secret of Secrets). It opens with a prologue whereby an anonymous author explains the circumstances in which the original Greek text had been written. Apparently, the author was Aristotle who, being too old to accompany his disciple Alexander in his campaign in Asia, wrote this book on the science of kingship as a kind of replacement for his absence. In the ninth century, the text was revised to make it look as a “Mirror of Princes”, so called because rulers were expected to look in this type of books as in a mirror. It also included a second prologue by the supposed translator of the work, Yahya ibn al-Bitrig, the name of one of the ninth-century scholars who prepared Arabic versions of Greek works for the Abbasid rulers in Baghdad. It is more likely, however, that a ninth-century compiler (pseudo-Yahya) modified the eighth-century Arabic manuscript at a time when the whole Aristotelian corpus was being translated into Arabic and anything attributed to the Greek philosopher would have a positive reception. The original Greek text was probably composed in Hellenistic times, already wrongly attributed to Aristotle, but partly based on a school-like version of the Nicomachean Ethics.

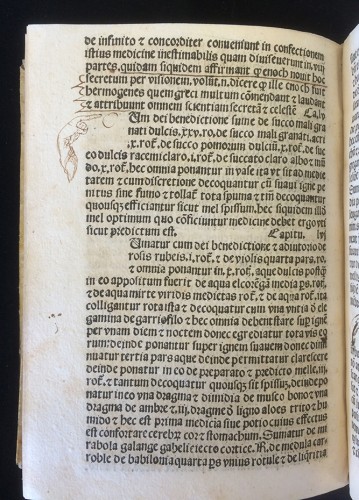

From the ninth century onwards, a series of revisers added material, transforming this treatise on kingship into a compendium of information that could be useful to anyone. For instance, a section on health was added, including topics like hygiene, diet, exercise, and medical astrology. For instance, the page on display contains precise advice about when to take certain medicines according to the position of the moon in relation with certain constellations. The Secret of Secrets was first introduced to the West through a Latin translation of a small portion of the work by John of Seville. Curiously, there was already interest on the health section as this Latin version is entitled Epistola Aristotelis ad Alexandrum de regimine sanitatis. Around 1230, it was translated into Latin in its entirety by Philip of Tripoli, massively circulating throughout the Middle Ages. Our copy is part of the Le Roy Crummer Collection , and knowing the great bibliophile skills of Dr. Crummer, I decided to explore whether he pursued the purchase of early printed editions of this work.

Pseudo-Aristotle. Utilissimus liber Aristotelis de secretis secretorum (Burgos: Andrés de Burgos, 1505)

Pseudo-Aristotle. Utilissimus liber Aristotelis de secretis secretorum (Burgos: Andrés de Burgos, 1505)

Indeed, and this early printed edition was avidly read as indicated by the manuscript underlining as well as the manicules pointing to relevant passages in the book. Not surprisingly, most of these annotations are in the medical sections of this treatise.

This manuscript, along with many other books and artifacts, will be on display in the exhibit, 'The Art and Science of Healing: From Antiquity to the Renaissance', at the Kelsey Museum of Archaeology and the Audubon Room of the University of Michigan Library, from February 10th to April 30th 2017.