We are thrilled to announce the acquisition of a nine-volume set containing satirical pamphlets, trial accounts, and legal and political commentaries, on the dramatic 1820 trial of Queen Caroline, the estranged wife of George IV, who faced charges of adultery in the House of Lords. Members of the pro-Queen side, such as the journalists William Hone and the illustrator George Cruikshank, saw the trial as an opportunity to highlight the importance of the freedom of the press and attack what they considered a corrupt government. Additionally, the "Queen Caroline Affair" inspired radical causes like the defense of women's rights.

Image of the spines of the five volumes containing 106 imprints in favor of the Queen's cause.

On the front pastedown of each volume is the bookplate of Sir Thomas Edward Winnington, 3th Baronet (1780-1839). An English Whig and Liberal politician, Sir Winnington witnessed the trial of Queen Caroline as a member of the House of Commons.

On April 8, 1795, Prince George of Wales, the eldest son of King George III, was coerced into a loveless marriage with his first cousin, Princess Caroline of Brunswick. Although Caroline and George spent only two nights together before their separation, they conceived a child: Princess Charlotte of Wales, born nine months after the wedding. As part of their separation agreement, Caroline secured assurance that, should Princess Charlotte die, she would not be compelled to produce another heir to the throne.

Despite this arrangement, persistent rumors and accusations of Caroline's alleged promiscuity gradually undermined the terms of their separation. The situation grew increasingly acrimonious after 1811, when Prince George was appointed Prince Regent. His extravagant lifestyle rendered him unpopular with the public, and he sought to tarnish Caroline’s reputation to secure a divorce. He also attempted to isolate her socially by excluding her from the Regency Court and imposing severe restrictions on her visits to their daughter.

Hand-colored etching depicting King George IV as a baby in a rose garden surrounded by three ladies. Roger Hunter. A Peep into the Cottage at Windsor; or, "Love among the Roses." A Poem, Founded on Facts. London: W. Benbow, 1821.

In 1814, Caroline left Britain to travel across Europe, but gossip about her purported “immoral” behavior persisted. Specifically, she was accused of having an intimate relationship with Bartolomeo Pergami, an Italian man she had employed in Milan.

When Princess Charlotte died suddenly in childbirth in November 1817, the bond between Caroline and George was irreparably broken, and Caroline’s hope of regaining her royal status vanished. George became more determined than ever to obtain a divorce, which required proof of Caroline’s adultery. In September 1818, Lord Liverpool organized the so-called “Milan Commission,” a team of investigators tasked with finding witnesses who could testify against Caroline’s conduct. However, before any resolution could be reached, King George III died on January 29, 1820, and George and Caroline ascended to the throne as King and Queen.

The day after Caroline returned to Britain on June 5, 1820, George informed the House of Lords that the Milan Commission had gathered incriminating evidence of Caroline’s adultery. Initially, a Bill to strip Caroline of her rights as Queen Consort and dissolve the marriage was discussed in the House of Lords. However, during the second reading, the proceedings evolved into a full trial, including the cross-examination of witnesses. Starting on August 17, 1820, the trial captured the attention of London publishers and booksellers. For the first time, the British public gained direct access to the private lives of the Royal family through various publications, including pamphlets, broadsides, and court reports. The sensational details of the trial, heavily reported and satirized, also exposed underlying social and ideological tensions in British society. The trial became an opportunity to debate significant issues, such as the role of the monarchy and the status of women. Many lamented Caroline's perceived unfair treatment, which was seen as reflective of broader gender biases. Indeed, while a husband’s adultery was not grounds for divorce, ecclesiastical courts would only grant a separation if the wife was found guilty of infidelity.

Unfolded hand-colored etching showing two gentlemen playing chess with each set of pieces representing the respective opposite sides: the King and the Queen. Philip Playfair. The Queen and her Pawns against the King and his Pieces; or the Royal Check-Mate: A Poem, with a Plate. London: W. Benbow, 1820.

Woodcut representing a ladder with the Queen sitting on top. Each step of the ladder is labeled with a grievance suffered by the Queen. The Queen Matrimonial Ladder, a National Toy, with Fourteen Step Scenes; and Illustrations in Verse, with Eighteen Other Cuts. London: William Hone, 1820.

Unfolded hand-colored etching depicting a caricature of "John Bull" in a living room covered with objects, each of which symbolically explains how the Six Acts passed in the emergency Autumn Session of 1819 have eroded individual freedoms. Geoffrey Gag-Ém -All. The Free-Born Englishman Deprived of his Seven Senses by the Operation of the Six New Acts of the Boroughmongers. A Poem. London: John Fairburn, 1820.

Image of the spines of the four volumes containing 58 imprints against the Queen's cause.

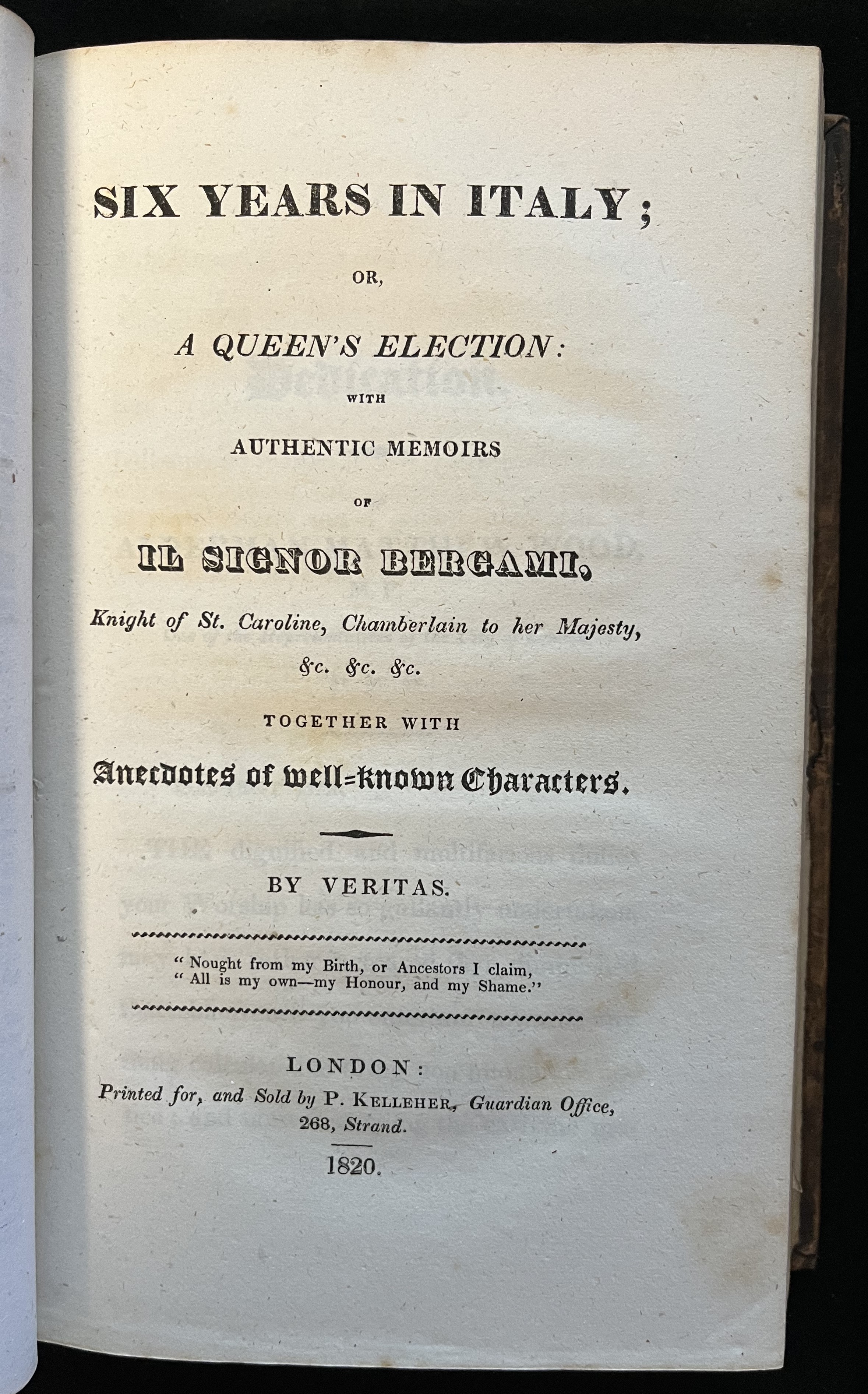

Title page. Six Years in Italy; or, A Queen's Election: with Authentic Memoirs of Il Signor Bergami, Knight of St. Caroline, Chamberlain to her Majesty. London: P. Kelleher, 1820.

Facing a page of text is a hand-colored etching depicting the Queen allegorically climbing a so-called "radical ladder" to obtain the crown located on top of a column. The Loyalist; or, Anti-Radical; Consisting of three Departments: Satyrical, Miscellaneous, and Historical. London: R. Gray, 1820.