Original paper binding of Irako Mitsuaki. Geka kinmō zui (Kyoto: Ebisuya Ichiemon, 1809)

We have recently purchased this very rare Japanese book on surgery for our History of Medicine Collection, which is particularly comprehensive on the history of surgery from the Middle Ages throughout the Renaissance. Since our holdings on this subject mainly focus on Western medicine, this Japanese imprint is a long overdue addition, being an extraordinary witness of one of many cultural exchanges between Japan and Europe from the sixteenth century onward.

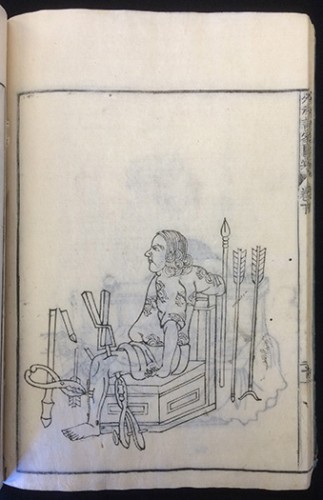

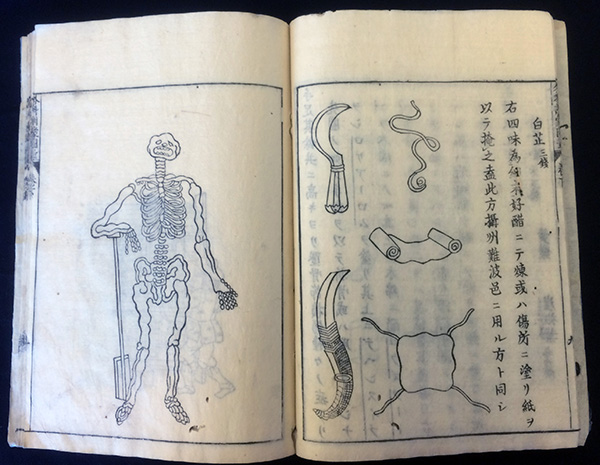

Woodcut from Irako Mitsuaki. Geka kinmō zui (Kyoto: Ebisuya Ichiemon, 1809)

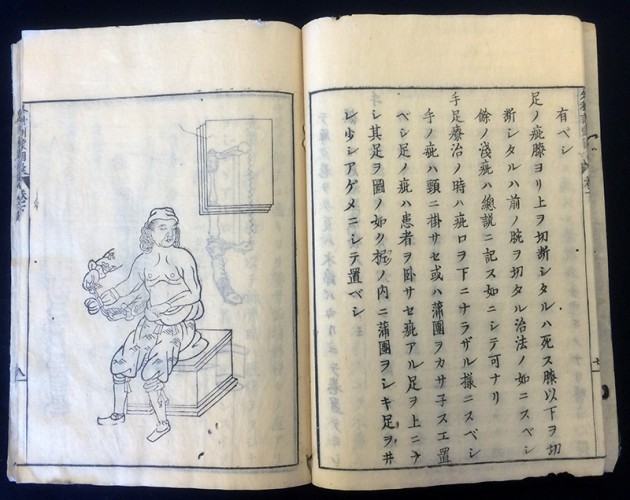

Originally published in 1764, our copy of Geka kinmō zui is not merely a reprint but a second edition that includes additional material. The treatise is divided into two volumes with a total of 48 full-page woodcut illustrations, mostly representing surgical operations performed on specific areas of the human body. A frequent woodcut in this book is the representation of a full human body pierced by a variety of weapons, thus demonstrating the wide range of injuries a surgeon might need to treat.

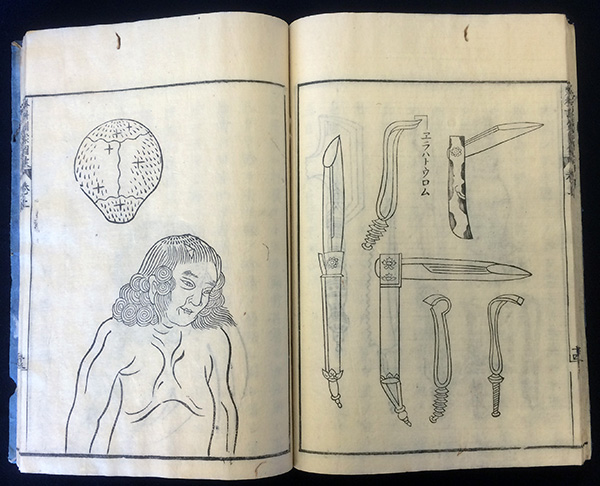

Essentially, the text of Geka kinmō zui is a translation of the Dutch work De Chirurgie, of which the Special Collections Library holds three early editions published in 1604, 1615, and 1636. In turn, De Chirurgie is a translation of Ambroise Paré's Dix liures de la chirvrgie, avec le magasín des instrumena necessaires à icelle, first published in 1564 and eventually re-published as part of Paré's complete oeuvres in 1575. Reasonably, the reader of this post might be now wondering why this Japanese translation is based on a Dutch text instead of using the original French. The brief explanation is that by the middle of the seventeenth century, the Dutch were the only Europeans living in Japan. The Portuguese and Spanish had been expelled, and the English had willingly departed. Just a small Dutch population remained on the artificial island of Deshima in Nagasaki harbor. While Dutch was almost exclusively used for commercial transactions, Dutch books started to be imported in large numbers, especially medical books for Japanese doctors interested in Western medicine. In 1771, Surgita Genpaku saw a copy of the Dutch edition of Johann Adam Kulmus's Anatomisch Tabellen (Anatomical Tables), using its illustrations to perform dissections. Impressed by the empirical accuracy of these illustrations, fairly unknown in Chinese and Japanese books on the subject, Genpaku arranged the Japanese translation of Kulmus's work. In 1774, Kaitai shinsko (New Book of Anatomy) was published, officially endorsing future translations of Dutch medical books.

Woodcut from Irako Mitsuaki. Geka kinmō zui (Kyoto: Ebisuya Ichiemon, 1809)

Woodcut from Irako Mitsuaki. Geka kinmō zui (Kyoto: Ebisuya Ichiemon, 1809) Woodcut from Irako Mitsuaki. Geka kinmō zui (Kyoto: Ebisuya Ichiemon, 1809)

Woodcut from Irako Mitsuaki. Geka kinmō zui (Kyoto: Ebisuya Ichiemon, 1809) Woodcut from Irako Mitsuaki. Geka kinmō zui (Kyoto: Ebisuya Ichiemon, 1809)

Woodcut from Irako Mitsuaki. Geka kinmō zui (Kyoto: Ebisuya Ichiemon, 1809)

A fascinating feature of this book is the fact that it was entirely printed by using woodblocks. This may seem odd, since the Japanese knew about the movable-type technique since the end of the sixteenth century. After the Jesuits introduced the first European press in Japan in 1590, movable-type and wood-block printing were in fact used interchangeably in Japan until the first half of the seventeenth century. While some books included both woodcuts and letterpress, as it was common in the Western tradition, others were entirely printed with woodblocks, like our featured title. However, by 1650, Japanese publishers abandoned the technique of movable-type and concentrated on woodblock printing exclusively. Why? There are several reasons. Firstly, it was extremely expensive to make single types replicating the vast quantity of logograms and kana (representations of syllabic sounds) in the Japanese language. Secondly, woodblocks could be stored for the re-printing of popular works in the future. And thirdly, by the first decades of the seventeenth century Japanese publishers tried to attract less-educated readers by including kana in the form of glosses clarifying the pronunciation of each logogram. But printers soon realized that it was hard to combine signs and glosses as individual types. Overall, movable-type printing did not re-appear in Japan until the mid-nineteenth century.