According to Giorgio Vasari’s collection of biographies, Le vite de piu eccellenti architetti, pittori, et scultori italiani (The Lives of the Most Excellent Italian Architects, Painters, and Sculptors) Leonardo da Vinci died on May 2, 1519. As museums and libraries around the world are commemorating the 500th anniversary of the death of Leonardo with various events and exhibits, we would like to join the celebrations of Leonardo’s legacy by highlighting our copies of some early printed editions of his Trattato della Pittura (Treatise on Painting).

Leonardo’s scattered notes and drawings on the science of painting, which were designed to instruct future painters in the principles of geometry and the art of the observation of nature, were first published as a printed book in Paris in 1651: astonishedly, 132 years after the death of the author! To be precise, two editiones principes, in French and Italian respectively, were published almost simultaneously. Special Collections holds a well-preserved copy of the 1651 French translation.

Engraved portray of Leonardo from Traitté de la Peinture de Leonard de Vinci. Donné au Public et Traduit d’Italien en François (Paris : Jacques Langlois, 1651)

Title-page from Traitté de la Peinture de Leonard de Vinci. Donné au Public et Traduit d’Italien en François (Paris: Jacques Langlois, 1651)

While early printed editions of the Treatise on Painting would have a great impact on the teaching of painting in art academies across Europe, the text and images of these editions misrepresent how Leonardo originally conceived this particular work. In general, the reason for this misunderstanding in the transmission of Leonardo’s ideas can be partly explained by how Leonardo recorded his thoughts and observations. His extant notebooks are compilations of single sheets of paper folded once to form a two-leaf folio, with four pages containing drawings and annotations on one, two, and sometimes even more subjects. Whereas some of the notebooks were practically ready for a future publication, others were early drafts waiting for further revisions that, unfortunately, never took place. More importantly, following Leonardo’s death in 1519, his notebooks were not expertly edited for publication as a whole corpus before they eventually ended up scattered in several European countries.

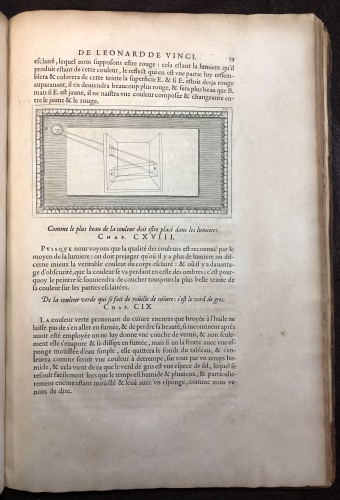

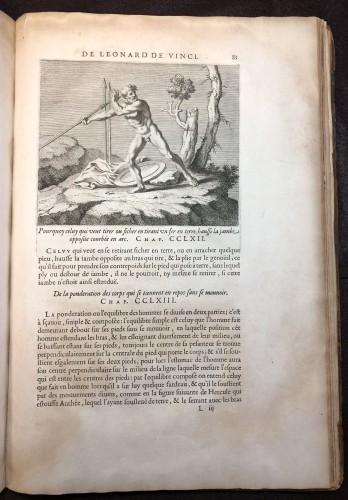

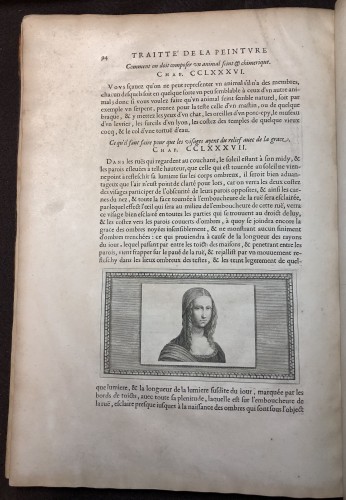

Traitté de la Peinture de Leonard de Vinci. Donné au Public et Traduit d’Italien en François (Paris : Jacques Langlois, 1651)

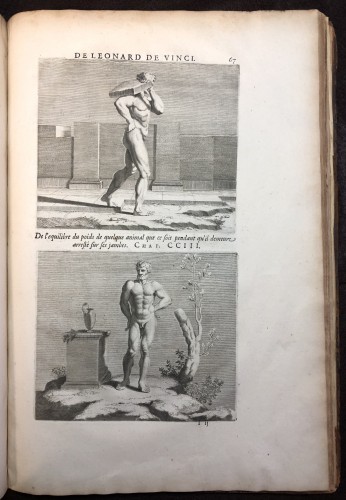

As stipulated in Leonardo’s testament, his pupil and friend, Francesco Melzi, inherited all his notebooks. Though Melzi might have tried to arrange all the material into a publishable form, he only managed to compile and edit notes on the topic of painting from eighteen notebooks, of which seven and a fragment are extant today. Moreover, in his selection and thematic arrangement, Melzi made numerous mistakes, almost exclusively emphasizing the repertoire of representational skills, whereas ignoring other aspects of Leonardo’s ideas on painting. The outcome of Melzi’s editing efforts was a single manuscript, now known as the Codex Urbinas Vaticanus 1270 and held in the Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana in Rome. Abbreviated copies of this manuscript, at that time held in the Barberini Library in Rome, circulated among artists and scholars for a century before one of these abridged versions was published in France in 1651. In brief, the idea for the French publication came from Cassiano dal Pozzo, scholar, antiquarian, patron of the arts, and secretary of Cardinal Francesco Barberini. Dal Pozzo commissioned an abridged copy of Melzi’s manuscript with the addition of drawings by the famous French painter Nicholas Poussin. The French translation was by Roland Freárt, sieur de Chambray, the brother of Poussin’s friend and patron Paul Freárt, sieur de Chantelou, who in 1640 brought the abbreviated copy of the Treatise on Painting to Paris. Furthermore, Melzi's misunderstanding of Leonardo’s ideas was exacerbated by the design of copperplate engravings of the 1651 edition. In a letter addressed to the engraver and professor of perspective Abraham Bosse, and quoted in the latter’s Traité des pratiques Géométrales et Perspective (Paris, 1665), Poussin strongly criticized this first edition. He complained that he designed drawings representing the human figure without those landscape backgrounds added by the engraver, Charles Errard. He also explained that the other engravings, mostly geometrical, were not his but based on drawings by Pierfrancesco Alberti.

Traitté de la Peinture de Leonard de Vinci. Donné au Public et Traduit d’Italien en François (Paris : Jacques Langlois, 1651)

Traitté de la Peinture de Leonard de Vinci. Donné au Public et Traduit d’Italien en François (Paris : Jacques Langlois, 1651)

Traitté de la Peinture de Leonard de Vinci. Donné au Public et Traduit d’Italien en François (Paris : Jacques Langlois, 1651)

Despite of its shortcomings, particularly in terms of the abridgement of the text and the dubious accuracy of the engravings, the Italian and French editions were widely used for the teaching of painting in Europe in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. Indeed, they were often reprinted and translated to other European languages. Ultimately, the editio princeps of the Codex Urbinas, that is, the manuscript containing Francesco Melzi’s unabridged compilation, would be published in 1817.

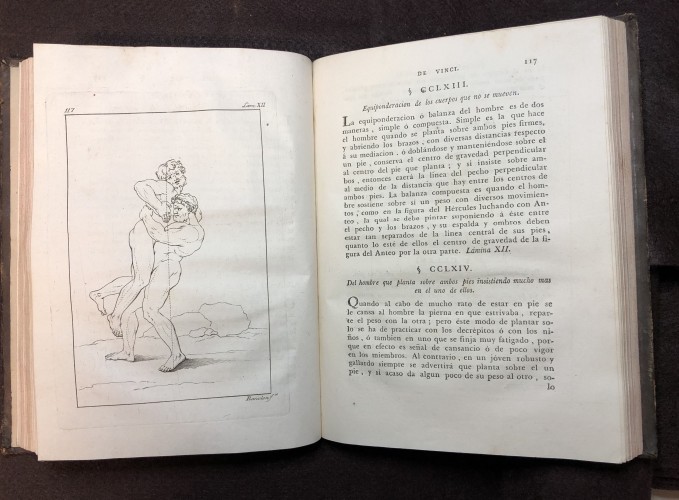

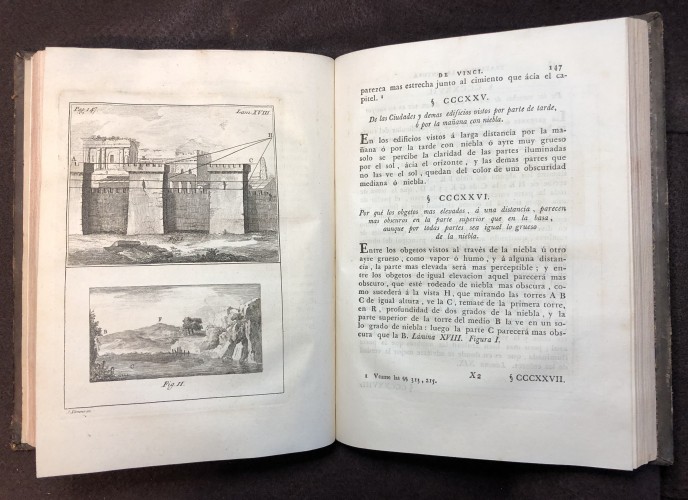

El Tratado de la pintura por Leonardo de Vinci, y los tres libros que escribió Leon Bautista Alberti : Traducidos é ilustrados con algunas notas por Don Diego Antonio Rejon de Silva (Madrid: Imprenta Real, 1784)

El Tratado de la pintura por Leonardo de Vinci, y los tres libros que escribió Leon Bautista Alberti : Traducidos é ilustrados con algunas notas por Don Diego Antonio Rejon de Silva (Madrid: Imprenta Real, 1784)

El Tratado de la pintura por Leonardo de Vinci, y los tres libros que escribió Leon Bautista Alberti : Traducidos é ilustrados con algunas notas por Don Diego Antonio Rejon de Silva (Madrid: Imprenta Real, 1784)

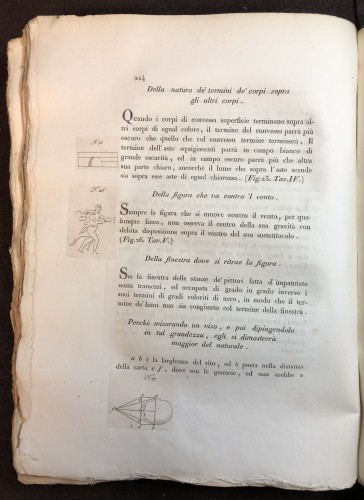

Trattato della Pittura di Lionardo da Vinci. Trato da un Codice della Biblioteca Vaticana e dedicato alla Maestá di Luigi XVIII Re di Francia e di Navarra (Rome: Stamperia de Romanis, 1817)

Selected Bibliography

Damish, Hubert. "A Tale of Two Sides: Poussin between Leonardo and Desargues". In The Treatise on Perspective: Published and Unpublished. Ed. Lyle Massey, 53-61. Washington: National Gallery of Art; New Haven & London: Yale University Press, 2003.

Farago, Claire. "How Leonardo da Vinci's Editors Organized his Treatise on Painting and How Leonardo Would Have Done It Differently". In The Treatise on Perspective: Published and Unpublished. Ed. Lyle Massey, 21-52. Washington: National Gallery of Art; New Haven & London: Yale University Press, 2003.

Kemp, Martin. ""A Chaos of Intelligence": Leonardo's "Traitté" and the Perspective Wars in the Académie Royale." In "Il se rendit en Italie": Études offertes à André Chastel". 415-426. Rome: Edizioni dell'Elefante ; Paris: Falmmarion, 1987.

Vasari, Giorgio. Le vite de piu eccellenti architetti, pittori, et scultori italiani: da Cimabue in sino à tempi nostri, descritte in lingua Toscana da Giorgio Vasari, pittore Aretino; con una sua utile & necessaria introduzzione a le arti loro. Florence: Lorenzo Torrentino, 1550.

Leonardo da Vinci: Libro di Pittura. Codice Urbinate lat. 1270 nella Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana. Ed. Carlo Predetti and Carlo Vecce. Biblioteca della Scienza Italiana 9. Florence: Giunti, 1995.