It is not uncommon that curators learn about the collections under their responsibility through questions from researchers. Two years ago we received the following inquiry from scholar and curator John Lancaster:

In the course of researching a book from Newton’s library that I recently was able to identify at Smith College, I came across a record in your catalogue for a book at Michigan that I strongly suspect was also in Newton’s library (record reproduced below).

The two bookplates (Huggins and Musgrave - the “Philosophemur” bookplate is that of James Musgrave) are strong indications that the volume stems from Newton’s library. Further information, with more detail about identifying the provenance, can be found in John Harrison’s The Library of Isaac Newton (Cambridge, 1978); Michigan holds a copy. Your volume would appear to match entry 1001 in Harrison.

The book in question includes two apocryphal alchemical treatises, wrongly attributed to the Majorcan philosopher Ramon Llull (c.1232-c.1315). Was our copy formerly owned by Newton? Indeed, it contains these two bookplates and other ownership marks confirming that this book was one day part of Newton's library. Why? Using Harrison's work as a guide, as Lancaster suggested, here is a brief overview of the dispersal of this library, including the steps any researcher or librarian should follow to determine this extraordinary provenance.

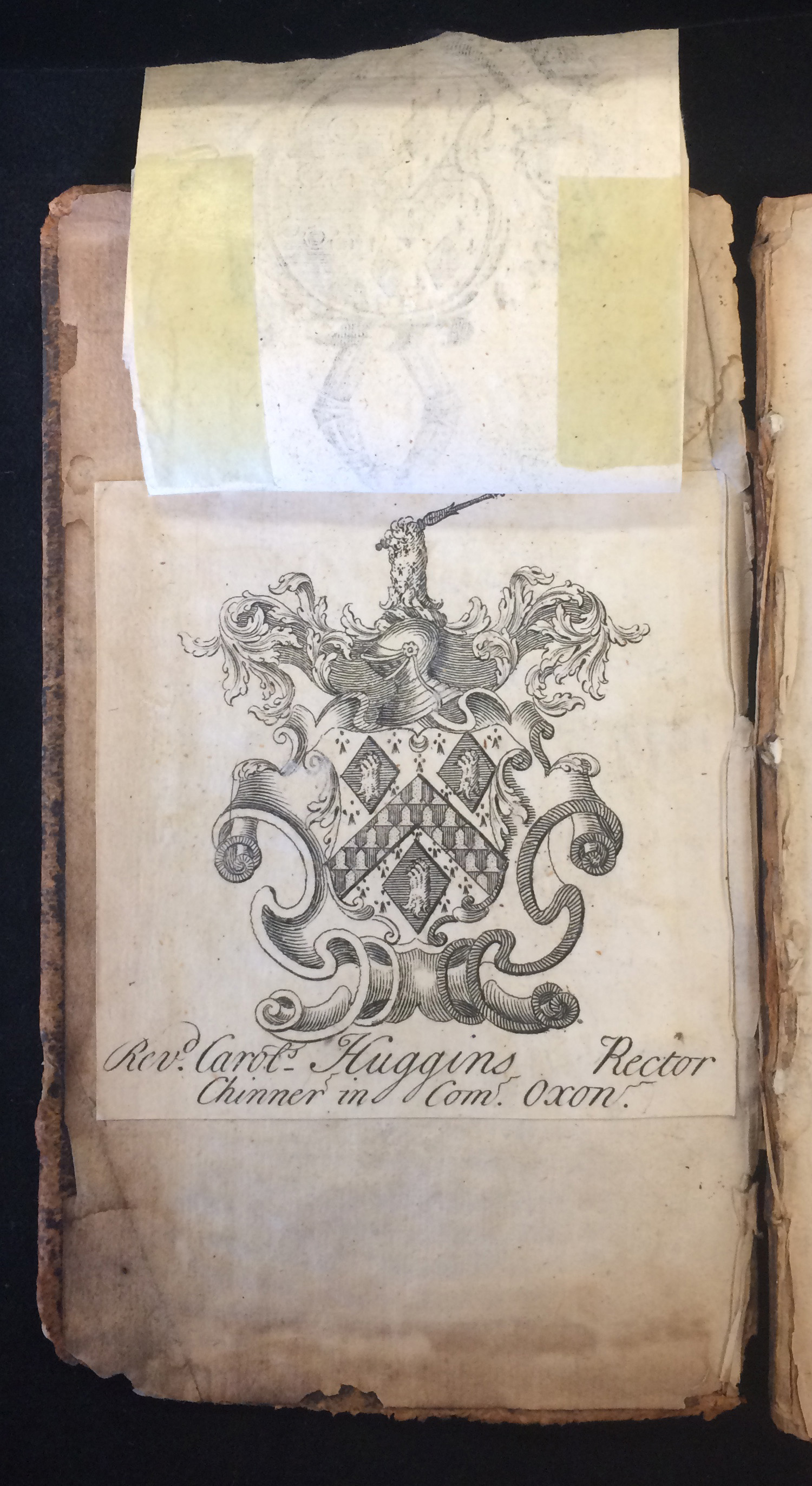

As Master of the Mint, Isaac Newton was responsible for all the outstanding debts of this institution even after his death. When he died in 1727, the Prerogative Court of Canterbury withheld Newton’s assets until a guarantor paid what he owed to the crown: £ 34,330. An inventory of Newton’s possessions was demanded by law, including the content of his extensive library. To be precise, the most exact record of Newton’s library is a list created just six weeks within Newton’s death. It is now held at the British Library and is commonly known as the Huggins List. In this list, books from the Newton's library are organized in descending order of format (folio, quarto, octavo, etc), and within each format the entries include author, title, number of volumes, date, and place of publication. Overall, the library contained at that time 1896 printed books along with a number of uncataloged pamphlets. Eventually, a purchaser of the books was found: John Huggins, the Warden of the Fleet Prison, paid £ 300 for the library. Perhaps in an attempt to improve the social and intellectual prestige of the family, Huggins presented these books to his third son, Charles, who had recently become Rector at Chinnor, a village near Oxford. Next, the books were transferred to the Rectory at Chinnor. In all the books, including Newton's library and his own, Charles inserted a bookplate bearing the Huggins coat of arms and the legend “Revd Carol(u)s Huggins, Rector Chinner in Com. Oxon.”

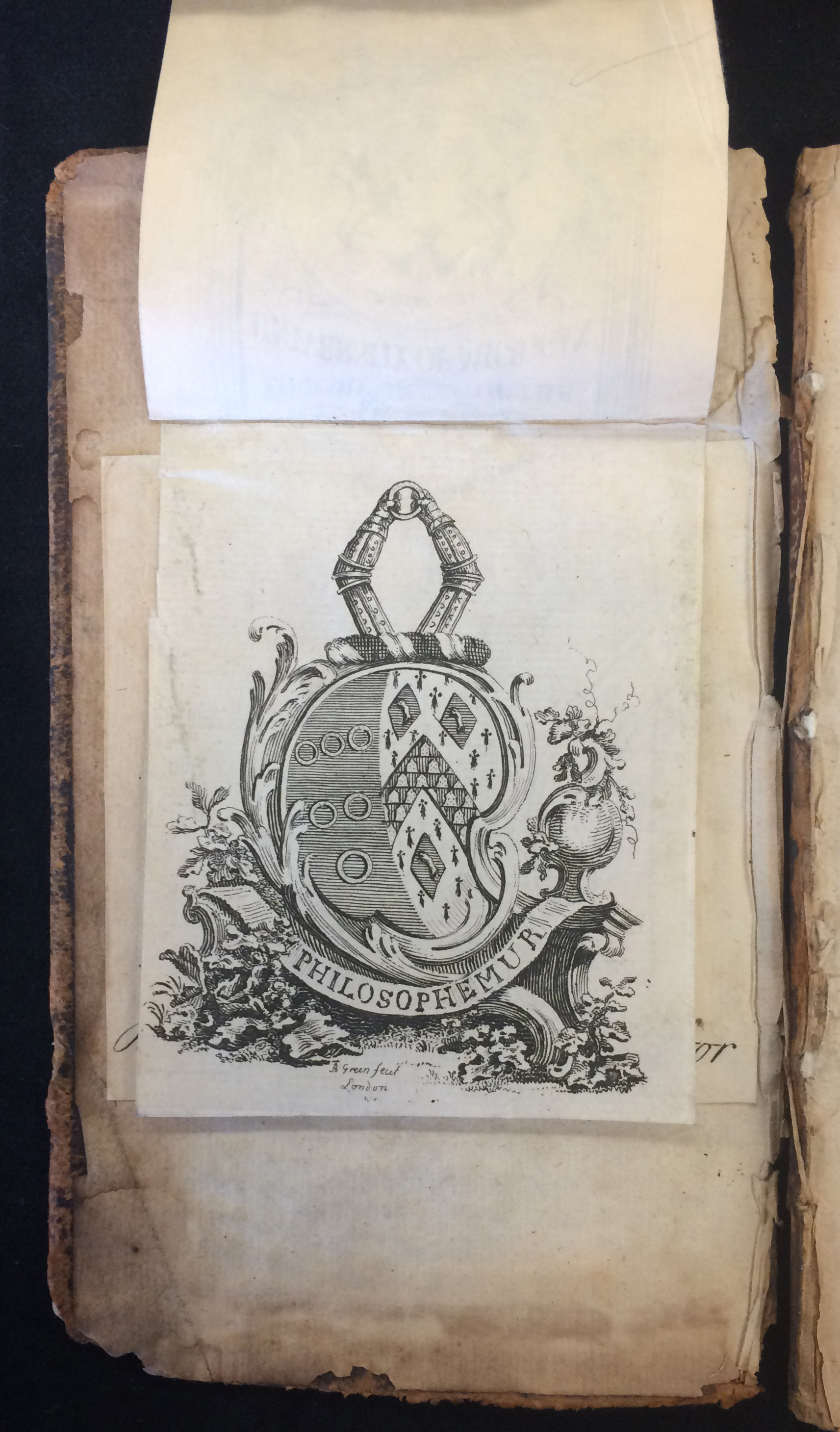

Charles Huggins died in 1750 a bachelor. His elder brother William administered the estate, giving the Rectory at Chinnor to his future son-in-law, James Musgrave. Then, the library was sold to the new Rector for £ 400. Contrary to his predecessor in the Rectory, Musgrave fully appreciated the historical importance of the library. He created a system to record the books and opened the library to visitors. The books were again shelved according to size, each volume being assigned a shelf mark written in ink, normally at the top left corner of the front pastedown or first flyleaf. The shelf mark consisted of a letter (bookcase) followed by a number (shelf), then a dash and another number (the position the book occupies on the shelf). In turn, Musgrave inserted his bookplate in every book: a combination of the coat of arms of both families, the Huggins and Musgrave, with the motto, Philosophemur.

The Chinnor library was moved to Barnsley Park (Gloucestershire) in or shortly after 1778. The owner of the estate, Cassandra Perrot, had left the house to her nephew James Musgrave, the son of James Musgrave, Rector at Chinnor. The latter died only a month after Miss Perrot's death in 1778, so James junior inherited both Chinnor and Barnsley. New shelf marks were added to the books; they were written along the lower edge of the Musgrave bookplate, again describing with letters and numbers the position of the books: bookcase, shelf, position of the book on the shelf, and the name of the main location,"Barnsley". The library remained very much intact, and unknown to scholars, until 1920, when a large portion was auctioned by Hampton & Sons. For many years books from this auction appeared in antiquarian catalogs, ending in private and institutional hands all over the world. In 1943, the Pilgrim Trust raised the funds for the purchase of 858 volumes of the Newton's library still remaining in Barnsley Park. Finally, these books were transferred to Newton's Alma Mater: they are held at the Wren Library, Trinity College, University of Cambridge.

In the image below, we can see Musgrave's shelf-mark system written in ink: E3-14. Thus the book was located in bookcase E, third shelf, an it was number 14 on that shelf.

U of M Library Bookplate on front pastedown of Pseudo Ramon Llull. Tractatus brevis et eruditus, de conservatione vitae; Liber secretorum seu quintae essentiae. Straßburg: Lazarus Zetnerus, 1616

And here is Musgrave's bookplate:

Musgrave's Bookplate on front pastedown of Pseudo Ramon Llull. Tractatus brevis et eruditus, de conservatione vitae; Liber secretorum seu quintae essentiae. Straßburg: Lazarus Zetnerus, 1616

And Huggins's bookplate:

Huggins's Bookplate on front pastedown of Pseudo Ramon Llull. Tractatus brevis et eruditus, de conservatione vitae; Liber secretorum seu quintae essentiae. Straßburg: Lazarus Zetnerus, 1616

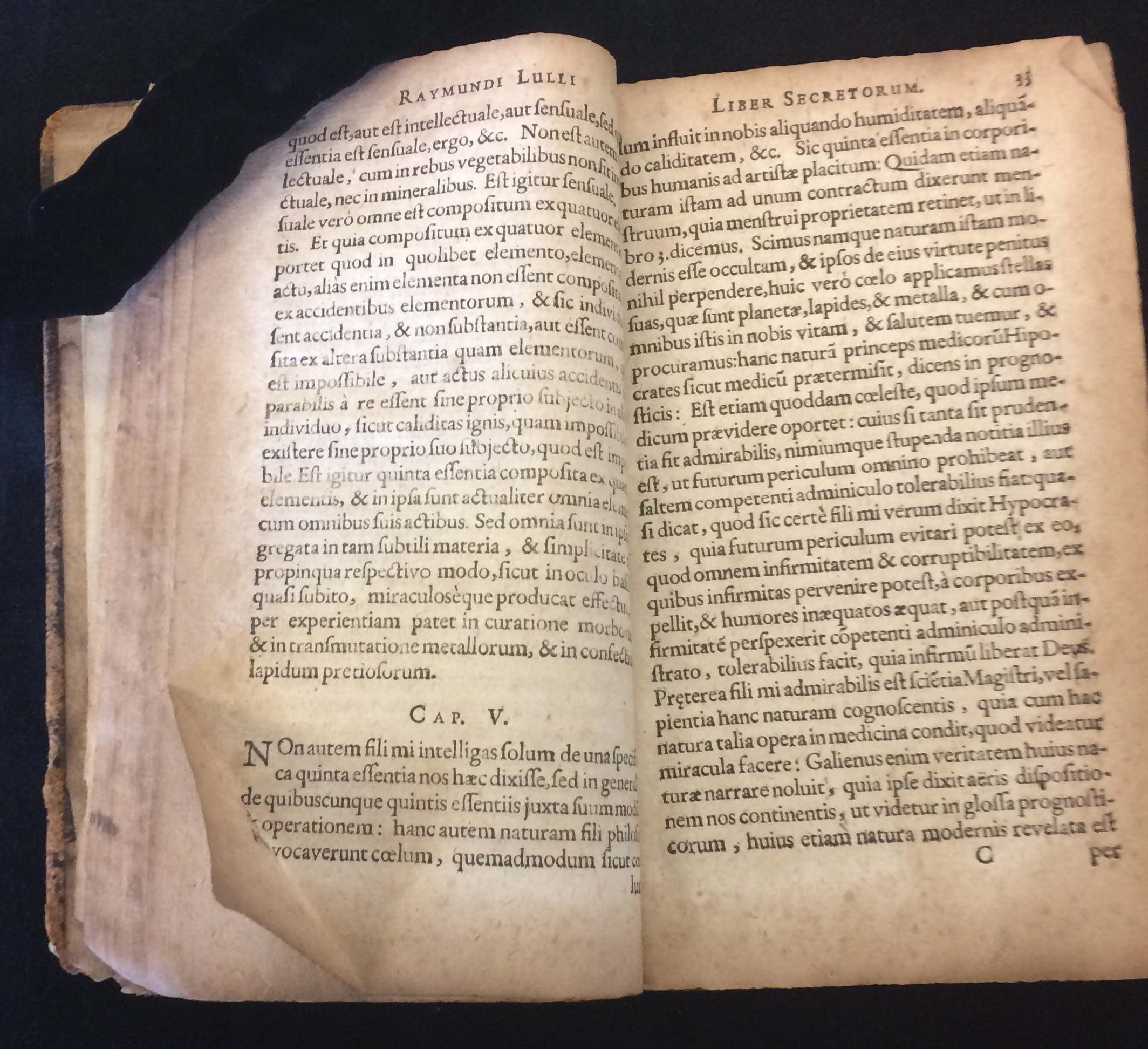

Of course, these are not entirely conclusive proofs since the shelf mark and the bookplates were consistently added in all the books, not only in those from Newton's library. But the additional evidence is that it is well known that Newton marked favorite passages in his books by dog-earing their pages, a practice clearly present in our copy. See image below:

Dog-eared page in Pseudo Ramon Llull. Tractatus brevis et eruditus, de conservatione vitae; Liber secretorum seu quintae essentiae. Straßburg: Lazarus Zetnerus, 1616

And the fascination with the dispersal of this library continues. Recently I received a similar inquiry about this same copy from Stephen D. Snobelen, Associate Professor of History of Science at the University of King’s College in Halifax, Nova Scotia (Canada). He is working on a project to fill the gaps in Harrison's catalog of Newton's library. In other words, there are still books from Newton's library whose location is still unknown. But extraordinary progress have been made in the last years. For instance, in this blog post, Dr. Snobelen describes a discovery he made when doing research in the Huntington Library.