The marks left by a book's former owners--inscriptions, drawings, clippings and other items laid in--can be an unexpected gift to the reader or researcher. Many studies of marginalia focus only on annotations that are related to the book’s text, but seemingly incidental inscriptions and doodles can be just as fascinating as scholarly notes. Folk rhymes left by former owners on the endpapers of their books can have much to say about the meaning and value of books as physical objects and symbols of status and knowledge.

Flyleaf rhymes date back to medieval scribes, but are especially common in school books from the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Children created many variations on rhymes that served to identify the owner, warn away potential thieves, and celebrate the book and what it represented. These examples from Special Collections' General and Rare holdings are open to interesting interpretations.

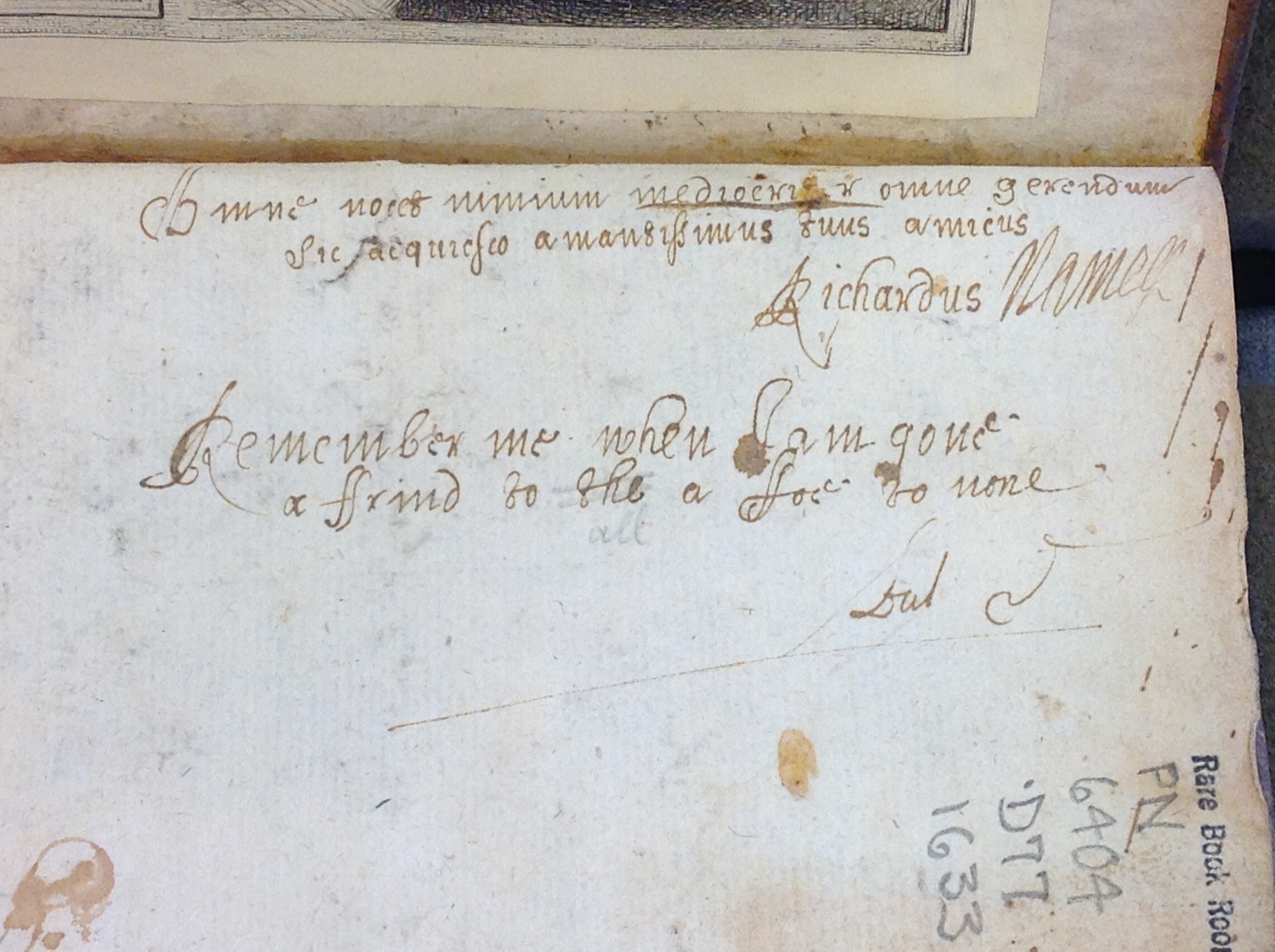

This book of proverbs includes an earlier example of a flyleaf rhyme: an English inscription commemorating the owner (“Remember me when I am gone / a fri[e]nd to the[e] a foe to none”) below a Latin inscription that is signed “Richardus.” Inscriptions can serve as a record or memorial of the owner that will long outlast him or her, and flyleaf rhymes often begin with or include the words “Remember me…” This rhyme also demonstrates the owner’s literacy in both English and Latin and is thus a marker of his scholarship.

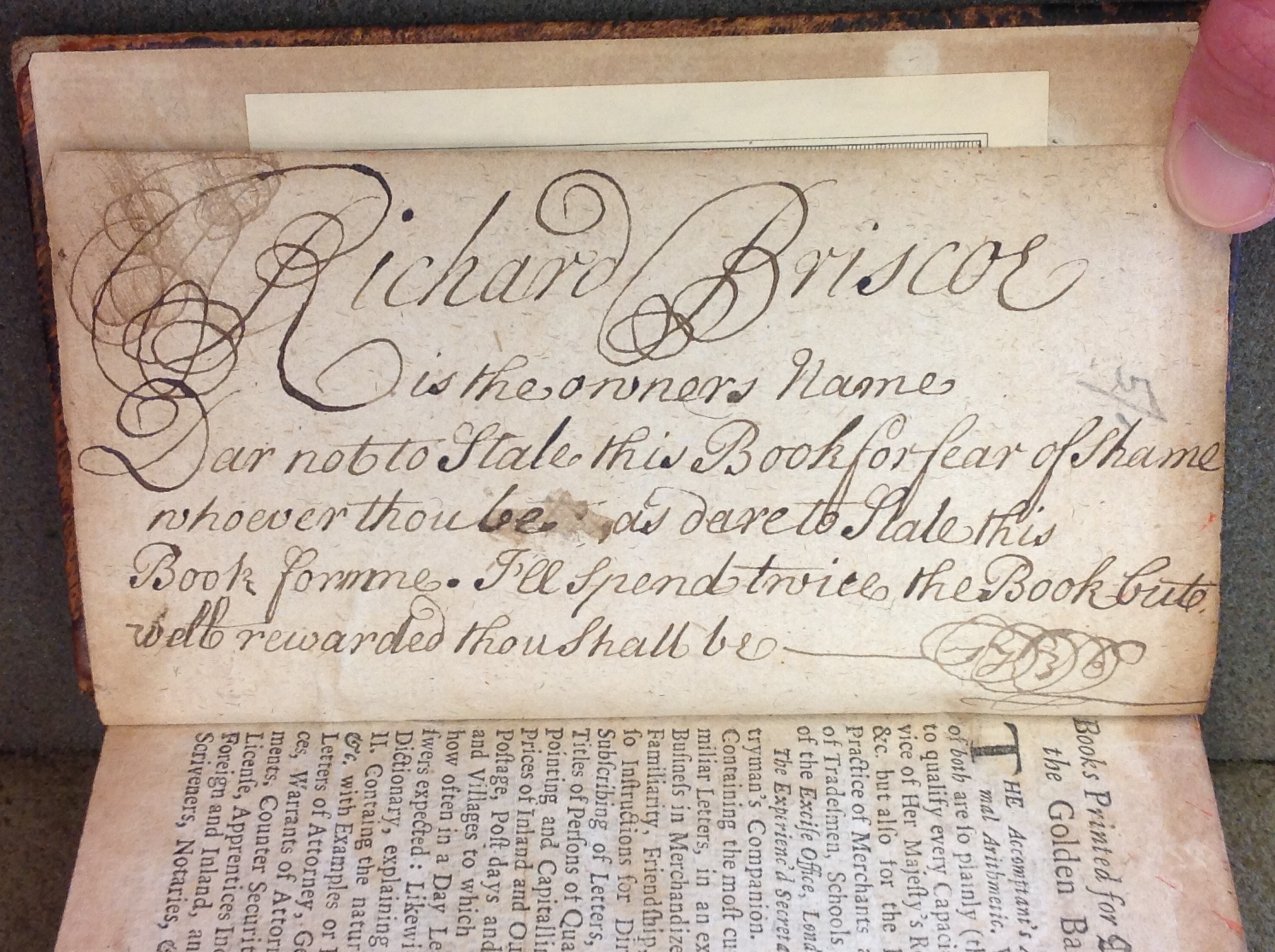

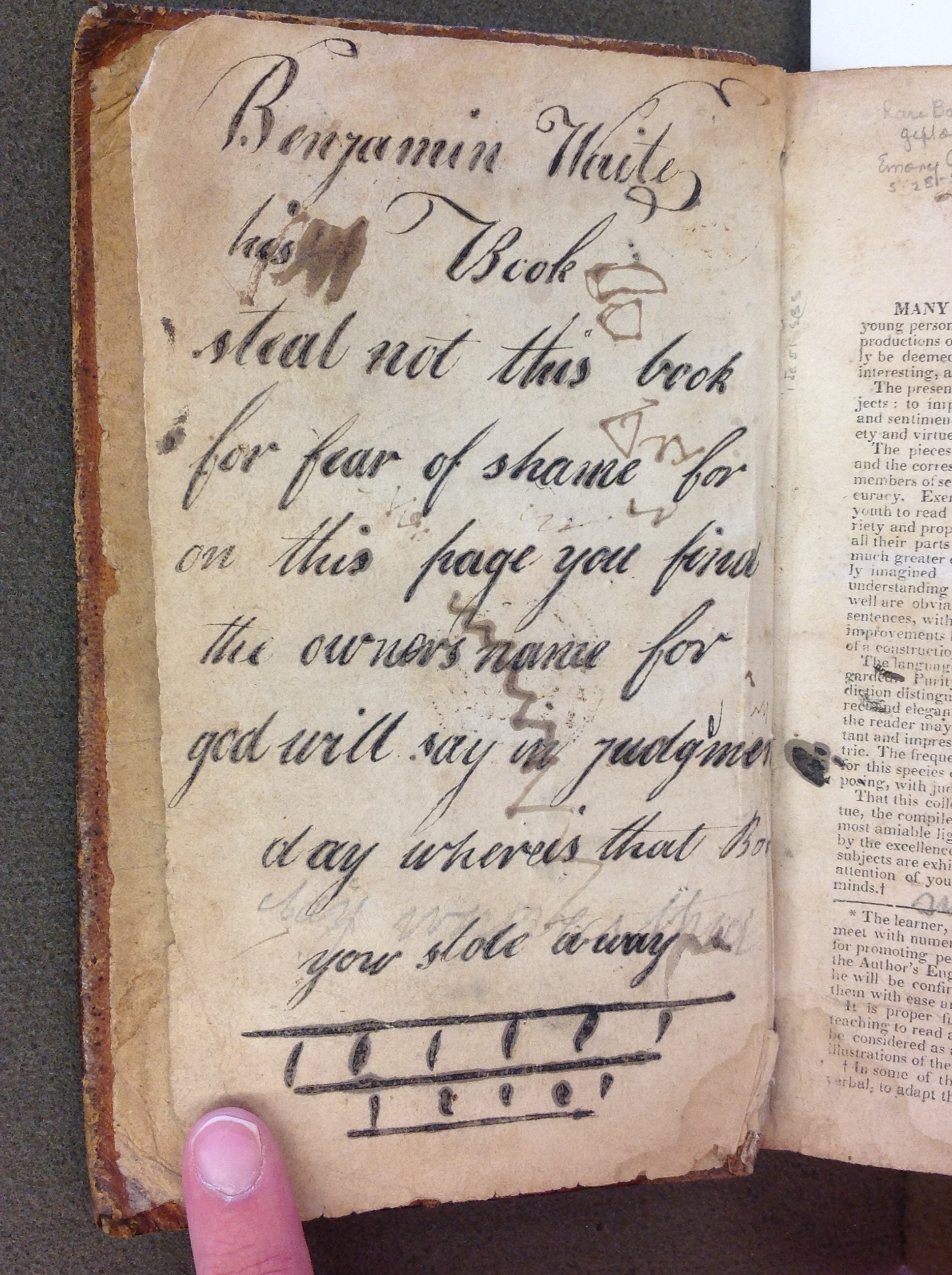

Other folk rhymes warn potential thieves as well as identifying the owner. Both of these rhymes—Richard Briscoe’s, dated 1736, and Benjamin Waite’s—threaten the book thief with “shame.” Waite’s inscription goes further: “for god will say [o]n judgment / day where is that Book / you stole away.” This focus on spiritual punishment reflects the focus on religion in eighteenth- and nineteenth-century American literacy instruction; the “English Reader” that the rhyme appears in combines Biblical content with classical and historical lessons.

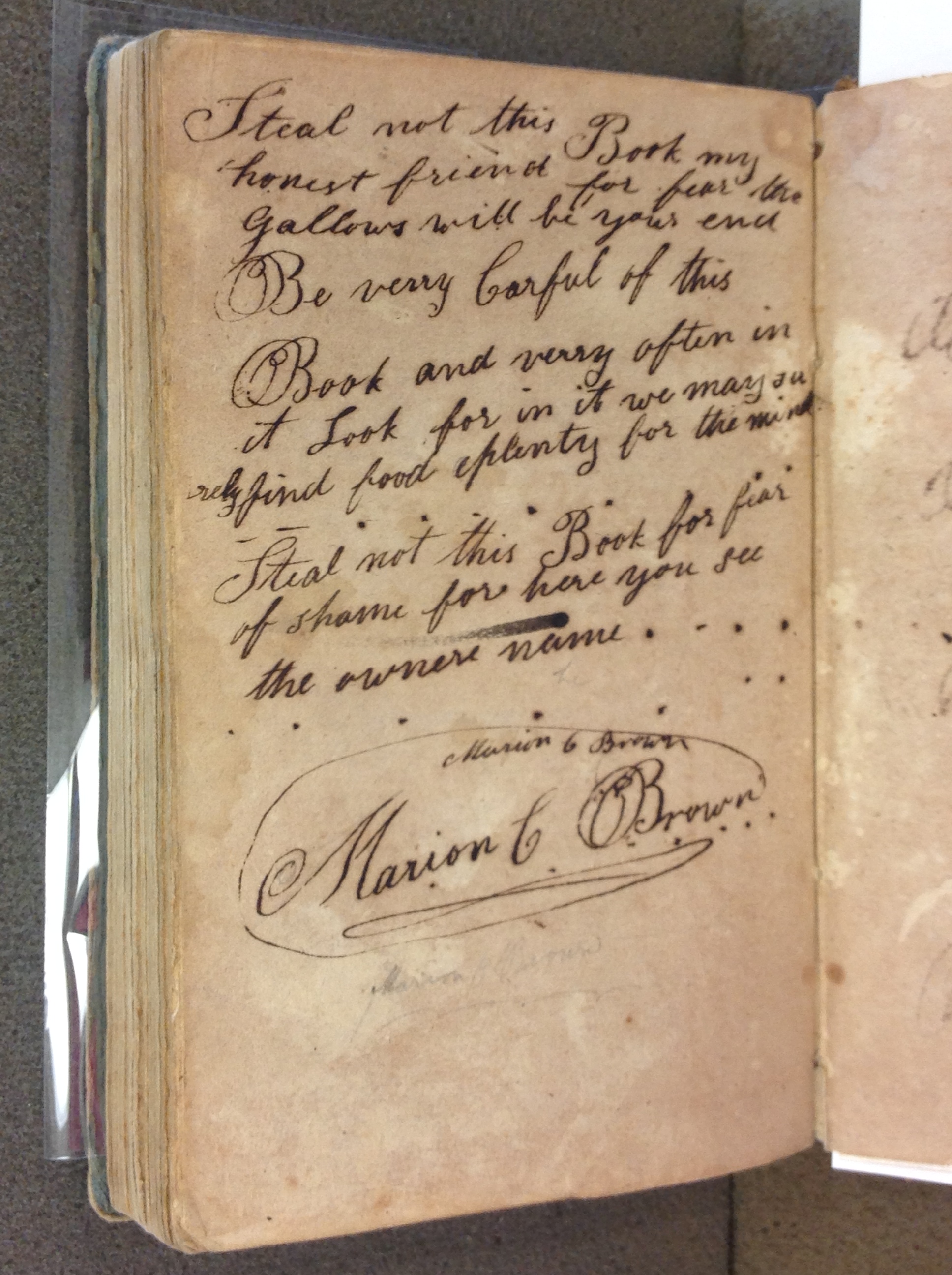

In this later edition of the same text, Marion C. Brown’s inscription combines several variations on folk rhymes. One threatens the thief with corporal punishment: “Steal not this Book my / honest friend for fear the / Gallows will be your end.” Another warns other readers to “Be very Car[e]ful of this / Book and very often in / it Look for in it we may su/rely find food aplenty for the mind.” This represents a third type of flyleaf rhyme that evokes the value of the book as an educational text.

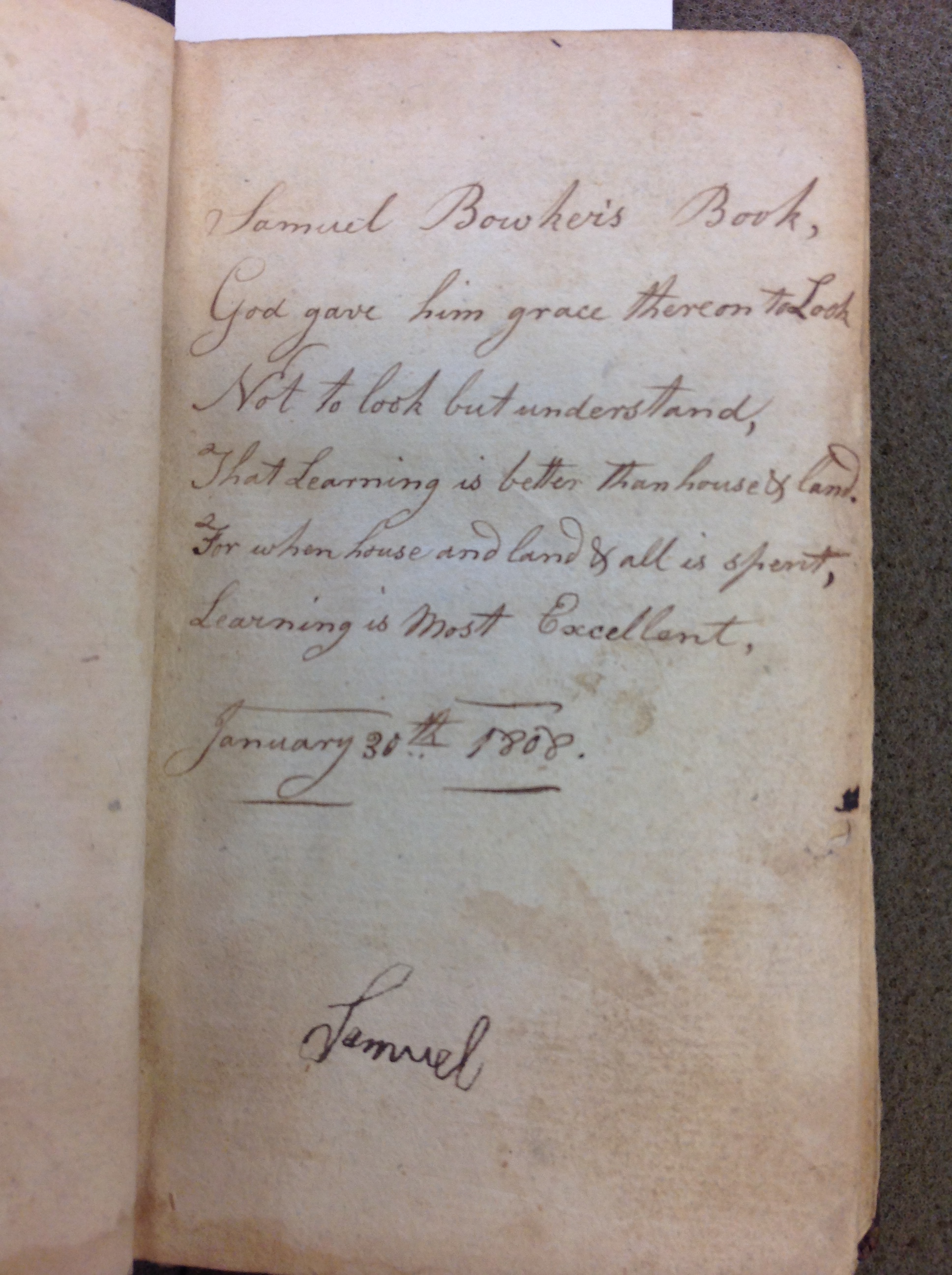

Another celebration of the book’s intellectual and spiritual value appears in this final flyleaf rhyme that celebrates learning as “better than house & land. / For when house and land & all is spent, / Learning is Most Excellent.” The rhyme is inscribed in a neater hand than the name at the bottom of the page, suggesting maybe it was a gift inscription from a parent or teacher.

These folk rhymes are not scholarly commentary on a text, nor were they left by significant historical personalities, but we nevertheless have much to learn from them about the importance of books to their owners. The variations among the rhymes also speak to the ways they would have been shared, likely in the schoolroom--copied from classmates' books, amended to suit the owner. These are just a few examples of many variations.

For those interested in learning more about flyleaf rhymes, some interesting studies appear in The Child Reader, 1700-1840 by M. O. Grenby (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2011) and Folklore and Book Culture by Kevin J. Hayes (Knoxville, TN: The University of Tennessee Press, 1997). My research on this topic and other types of manuscript evidence found on endpapers will appear in the upcoming second volume of Suave Mechanicals: Essays on the History of Bookbinding from The Legacy Press.

Written by Rosa Moore.