While the great historical novelty of the microscope was that it disclosed a previously unseen natural world without having to use dissection, often a destructive method, Hooke had to make a concession when dealing with the large head of the drone-fly. He might have asked himself: is this really a functioning eye? Hooke dissected the eye to examine its structure, finding that it consisted of three elements: an outer transparent layer (cornea); a clear liquid inside the cornea; and a mucous lining (retina) inside the cavity of the eye, with the type of pigment that determines the color of the eyes of insects in general. In fact, this structure, Hooke observed, is present in the eye of any vertebrate. Next, according to the laws of refraction, Hooke determined that each of those small hemispheres refracts parallel ray lights into a point on the retina. Thus, each hemisphere works like a perfect eye.

This engraving, along with its explanatory text, is part of Hooke’s masterpiece, Micrographia (Microscopy), published in the last day of 1664, even though the title page indicates 1665.

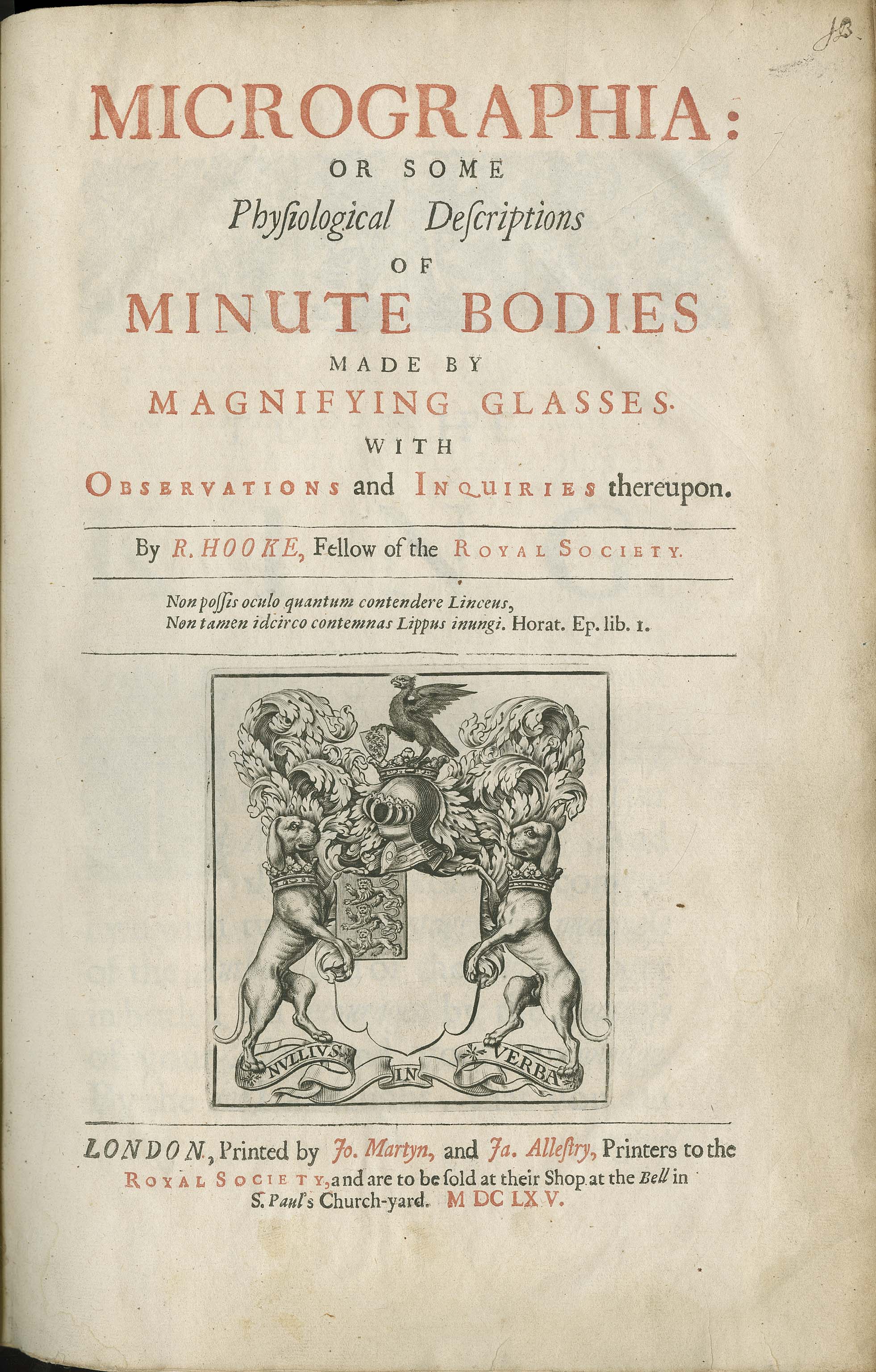

Title page of Micrographia. London: John Martyn & James Allestry. Printers of the Royal Society, 1665

The book includes 57 microscopic and 3 telescopic observations. Hooke begins by studying inorganic matter, turning into the scrutiny of vegetable and animal specimens. As exemplified by the examination of the eye of the drone-fly, Hooke’s method echoes the new science then promoted by the Royal Society and the European scientific community: a scientific theory must depend on observation not on previous authority alone.

The Micrographia was a tremendous publishing sensation that transcended the traditional limits of the scientific milieu. The details of many tiny creatures could be seen for the first time on carefully designed copperplate engravings. Many of these plates were in fact drawn by Hooke himself.

Plate 34, a flea, a creature easily found in seventeenth-century London, from Micrographia. London: John Martyn & James Allestry. Printers of the Royal Society, 1665

Stay tuned: the Micrographia will be part of an exhibit about the history of the microscope, opening on April 8.