As I thumbed through letters between Danny Kaye and his sweetheart Holly Fine, I couldn’t help but imagine the ginger-haired actor twirling Vera-Ellen in his arms and singing “The Best Things Happen While You're Dancing.” We often think about film as a moving media––people and objects flickering across screens––but film archives, like those of the Special Collections Library, contain the material, tangible objects that accompany the making of films.

These materials tell rich stories. For example, the correspondence between Fine and Kaye, which dates to about twenty years before his appearance in White Christmas, offers a detailed, if limited, glimpse of their off-stage romance. These letters are a part of the Holly Fine and Danny Kaye Papers (1934-1994), a collection on the life of a vaudeville entertainer who traveled around the world. In addition to Kaye’s letters to Fine, the collection contains pictures and scrapbooks of Fine’s work in show business and of her travels to China, Japan, India, South Africa, Mexico, and Australia.

(From left) Holly Fine, Danny Kaye, and friends later in life, from the Holly Fine and Danny Kaye Papers

(Photo courtesy of Annika Pattenaude)

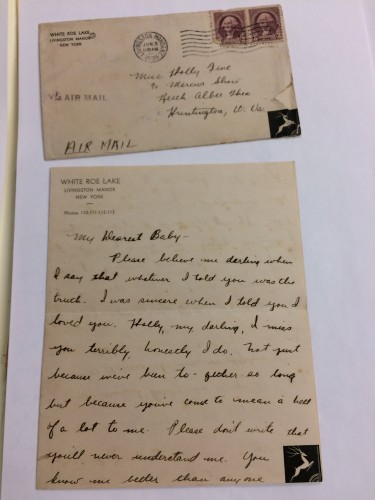

The letters Kaye writes to Fine, which span about three years, tell one narrative of their relationship. One letter begins:

Letter from Danny Kaye to Holly Fine, from the Holly Fine and Danny Kaye Papers (Photo courtesy of Annika Pattenaude)

“Dearest Baby,

Please believe me darling when I say that whatever I told you was the truth. I was sincere when I told you I loved you. Holly, my darling, I miss you terribly, honestly I do. Not just because we’ve been to-gether so long but because you’ve come to mean a hell of a lot to me. Please don’t write that you’ll never understand me. You know me better than anyone…”

In my last blog post, I mentioned some super-cool, uncatalogued collections that I’ve encountered this summer as a Mellon Public Humanities Fellow in the Special Collections Library. In the library's Screen Arts Makers and Mavericks finding aids, you can find well-known names like Robert Altman, Orson Welles, and John Sayles. Each collection tells a material and textual story about film production far more intricate than what the films alone can tell.

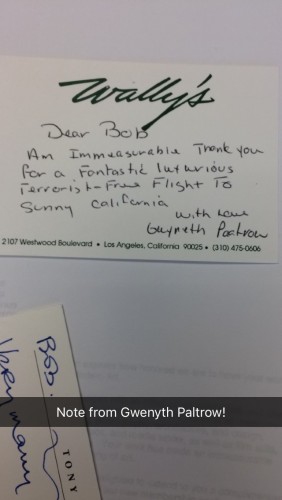

For instance, the collection donated by Robert Shaye, founder and former CEO of New Line Cinema, includes a handwritten thank-you note from Gwyneth Paltrow and a letter from Jane Fonda.

Note from Gwyneth Paltrow to Robert Shaye, from the Robert Shaye-New Line Cinema Papers

(Photo courtesy of Annika Pattenaude)

Aside from detailed notes, drafts, memos, and company records from New Line Cinema, Shaye’s collection also contains almost everything you would ever want to know about the making of The Last Mimzy, including visual arts research, movie soundtracks, and focus group survey results.

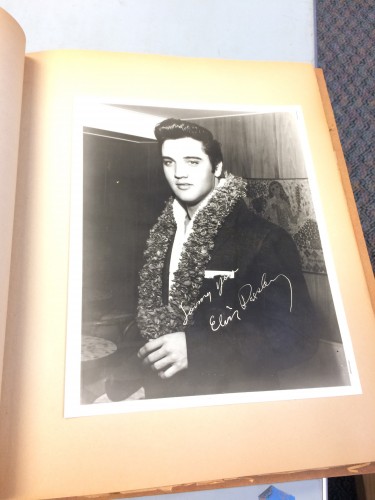

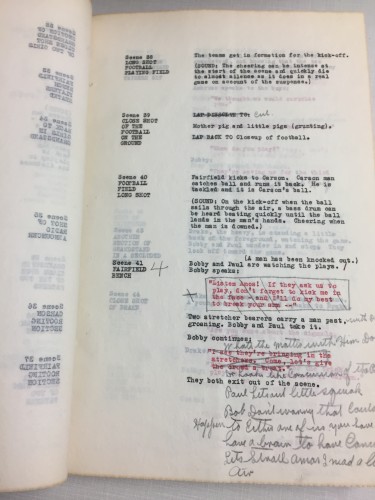

Not all film collections are so well-documented. One obscure, unprocessed film collection I encountered in the archives was the Norman Taurog Papers. Norman Taurog was an award-winning American film director and screenwriter. His films included six Martin and Lewis films and nine Elvis Presley films––which is likely why the collection contains an enthusiastic scrapbook on “the King,” including an autographed photo. The collection also holds three volumes of scripts Taurog directed, filled with handwritten edits, such as “Football Story for Clark and McCullough” (pictured below).

Autographed photo of Elvis Presley, from the Norman Taurog Papers (Photo courtesy of Annika Pattenaude)

Handwritten notes and edits in a script from the Norman Taurog Papers (Photo courtesy of Annika Pattenaude)

My quick descriptions of these various film collections are eclectic and somewhat random, but hopefully, I’ve whetted your tastebuds. The Screen Arts Mavericks & Makers and other archival collections in the Special Collections Library record a unique and colorful history of film production, but these stories often go unheard until a researcher takes the lid off the archival box. Personally, I had no idea Danny Kaye was into vaudeville.